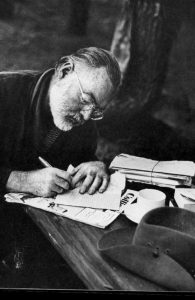

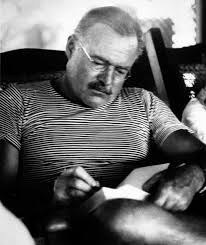

So! What say you? Are these the 100 Greatest Novels ever? There can only be one per author (Explaining why there is only one Hemingway novel on the list!) These are not in any order of greatness but are merely alphabetical. So here you go. PBS has put this together so read Jay Oliver’s article. Interesting!

Jay Oliver

moliver@yakimaherald.com May 23, 2018

Using the public opinion polling service “YouGov,” PBS and its producers conducted a demographically and statistically representative survey asking around 7,200 Americans to name their most-loved title, according to the web page. PBS said tallied results were organized by an advisory panel of 13 literary professionals.

Criteria allowed for works of fiction from all over the world, as long as the novels were published in English. They allowed only one title per author.

Reporters and editors in the Yakima Herald-Republic’s newsroom were given copies of the list to find out which titles were the most popular — and to see who’s read the most from their newsroom staff.

The most widely read title by newsroom respondents is Harper Lee’s “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Two books tied as the second most-read — “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” by Mark Twain and E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web” — while George Orwell’s “1984” was the third most widely read in the newsroom.

John Steinbeck’s “The Grapes of Wrath” and “Great Expectations” by Charles Dickens tied with C.S. Lewis’ “The Chronicles of Narnia” series as the fourth most read titles.

Rounding out the top five was F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” which was read by as many folks as two other series — J.R.R. Tolkein’s “The Lord of the Rings” and “Harry Potter” from J.K. Rowling.

Here’s the List (alphabetical not by greatest of the great.)

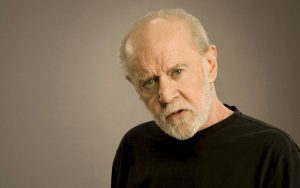

1984 by George Orwell

A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole

A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving

A Separate Peace by John Knowles

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho

Alex Cross Mysteries (series) by James Patterson

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie

Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Another Country by James Baldwin

Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand

Beloved by Toni Morrison

Bless Me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz

The Call of the Wild by Jack London

Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Charlotte’s Web by E.B. White

The Chronicles of Narnia (series) by C.S. Lewis

The Clan of the Cave Bear by Jean M. Auel

The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah

The Color Purple by Alice Walker

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time by Mark Haddon

The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Doña Bárbara by Rómulo Gallegos

Dune by Frank Herbert

Fifty Shades of Grey (series) by E.L. James

Flowers in the Attic by V.C. Andrews

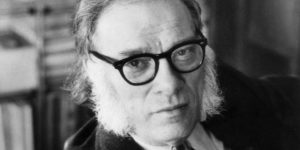

Foundation (series) by Isaac Asimov

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Games of Thrones (series) by George R.R. Martin

Ghost by Jason Reynolds

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

The Giver by Lois Lowry

The Godfather by Mario Puzo

Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Great Expectations by Charles Dickens

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Harry Potter (series) by J.K. Rowling

Hatchet (series) by Gary Paulsen

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

The Help by Kathryn Stockett

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

The Hunger Games (series) by Suzanne Collins

The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy

The Intuitionist by Colson Whitehead

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

Jurassic Park by Michael Crichton

Left Behind (series) by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins

The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry

Looking for Alaska by John Green

The Lord of the Rings (series) by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold

The Martian by Andy Weir

Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden

Mind Invaders by Dave Hunt

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

The Notebook by Nicholas Sparks

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

Outlander (series) by Diana Gabaldon

The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan

The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier

The Shack by William P. Young

Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse

The Sirens of Titan by Kurt Vonnegut

The Stand by Stephen King

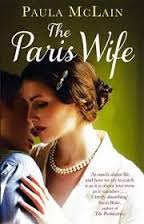

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Swan Song by Robert McCammon

Tales of the City (series) by Armistead Maupin

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

This Present Darkness by Frank E. Peretti

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Twilight Saga (series) by Stephenie Meyer

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

The Watchers by Dean Koontz

The Wheel of Time (series) by Robert Jordan

Where the Red Fern Grows by Wilson Rawls

White Teeth by Zadie Smith

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

This is me: Hmm. Food for thought. I was at first shocked that For Whom the Bell Tolls was not here but as noted, only one book per author permitted. Happy Memorial Day to all! C