Hemingway Birthday Lecture with Prof. J. Gerald Kennedy

- Jul 19 at 3:00PM – 4:30PM

-

834 Lake Street

Oak Park

60301 - Free

All about Hemingway

Of course, preeminent American humorist Mark Twain most famously announced that “reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” but he actually had to do it twice. The first time, his cousin’s illness resulted in a game of telephone that led to his notorious quip, but 10 years later, after The New York Times reported that his boat was lost at sea, he wrote an article for the same newspaper investigating his own possible death. At least, after both mistakes, we got some great writing out of it.

Alice CooperUnlike most such mistakes, Melody Maker knew exactly what they were doing when they published a satirical obituary of Alice Cooper in 1973. They were talking about the death of his career, but so many fans reached out to them in confused anguish that they had to publish a retraction, quoting the man himself as saying, “I lost $4,000 … at blackjack last night. I could have died!” and “Am I alive? Well, I’m alive and drunk as usual.”

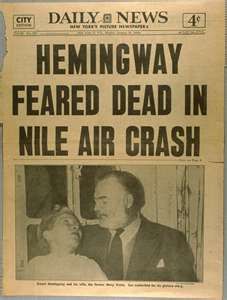

To be fair, it wasn’t that big of a leap to assume that Hemingway had died in a plane crash in Africa in 1954. He was hurt very badly, and he’d actually been involved in two plane crashes, and it’s not like the mid-1950s were a great time for surviving such incidents. But survive, he did, and he was so amused by his own obituaries that he collected them in a scrapbook to read every morning over a glass of champagne. We like Twitter and cold brew, but you do you, Ernie.

As morbid as it might seem, a lot of famous people’s obituaries are written ahead of time. People are on deadlines, and you know, sometimes the writing’s on the wall, so it might as well be in the CMS. That practice came back to bite CNN in 2003, however, when trolls found out they could access the news organization’s stockpile of unpublished obituaries, which didn’t remain unpublished for long. The best part is that they appeared to be placeholders full of wildly inaccurate filler, mostly based on the obituary of the Queen Mother, who had died the previous year. For example, former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney was described as “the U.K.’s favorite grandmother.” Cheney has been called a lot of things, but definitely never that.

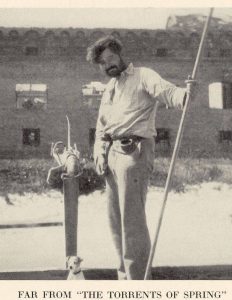

This is a familiar debate for Hemingway scholars and us amateur scholars. I added a few photos. You be the judge.

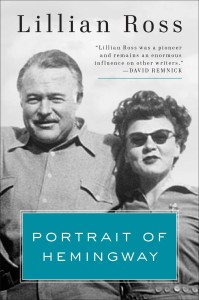

As the current custodian of the letters from Ernest Hemingway to Lillian Ross, I’d like to add a bit of context to Adam Gopnik’s recent piece about Ross’s Profile of the novelist (A Critic at Large, February 17th & 24th). Immediately after leaving Ross in New York, Hemingway wrote to her from the S.S. Île de France, “And you can write any god-damn thing you want except we must avoid lible and hurting people and get the names right”—instructions Ross underlined. When Ross sent Hemingway the Profile proofs, asking for his “corrections and changes” prior to publication (now a bygone practice), he demurred: “I will say nothing about the piece because according to my code if you change, alter or correct then you authorize a piece. Hope I don’t talk that way; but if that is how it sounds to you then you have a perfect right to write it that way.” He did ask her to “delete any reference to my mother,” gave vague answers to her questions about a scar and the coat of arms on his suitcase, and thanked her for “laying off the war and all the things you could have written that people don’t know.”

In a subsequent letter, after Hemingway reread the proofs, he wrote to Ross, “It is a good, funny, well intentioned, well inventioned piece,” and predicted, “Piece will make me many, many enemies,” adding, “But I guess an enemy is not nearly as dangerous, basically, as a friend.” In quoting this, Gopnik left out “well inventioned”—Hemingway’s clear nod to the creative slant that he perceived in Ross’s Profile—as well as his perhaps pointed evaluation of the relative dangers from friends and from enemies.

Sarah Funke Butler

Providence, R.I.

•

Letters should be sent with the writer’s name, address, and daytime phone number via e-mail to themail@newyorker.com. Letters may be edited for length and clarity, and may be published in any medium. We regret that owing to the volume of correspondence we cannot reply to every letter.

HAVANA, Cuba, Jun 10 (ACN) Promoting the life and work of U.S. writer and journalist Ernest Hemingway based on recent research is the main goal of the 20th International Colloquium named after the 1954 Literature Nobel prizewinner, to be held on June 25 to 28 in Havana.

According to Isbel Ferreiro Garit, deputy director of the Finca Vigia Museum, the event also intends to highlight several commemorations related to the author of The Old Man and the Sea, among them the 90th anniversary of the first publication of the novel Green Hills of Africa (1935), the 85th anniversary of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940) and the 65th anniversary of the conclusion of A Moveable Feast (1960), as well as the important meeting he held 65 years ago with Fidel Castro Ruz.

The event will feature the presentation of research works made by scholars, academicians, university professors, and Cuban and foreign writers―including eight papers prepared by participants from Japan, Argentina, Canada and the United States―in addition to a digital version of the novel The Sun Also Rises and La Habana de Hemingway y otros relatos, by the renowned Cuban journalist and essayist Ciro Bianchi Ross.

Visits to sites where the famous American novelist left his mark, such as the restaurant Terraza de Cojimar, the Club Nautico, the bars El Floridita and Sloppy Joe’s, and Finca Vigía―his Cuban home―will also be part of the program.

Ernest Hemingway vs. John Steinbeck: Which Literary Titan Captured the American Spirit Best? (Picture Credit – IMDB)

GIRISH SHUKLAAUTHORA dedicated bibliophile with a love for psychology and mythology, I am the author of two captivating novels. End of Article

Series. A miniseries based on the true story of the friendship between Ernest Hemingway and Morley Callaghan in Toronto and Paris between 1923 and 1929.

Gordon Pinsent portrays the older Morley Callaghan and Maury Chaykin takes on the role of Max Perkins.

Film (2024). On a desolate, Midwestern county road, a bound man crawls towards a remote postal box, managing to slide a blood-stained plea-for-help message into the slot before a panicking figure closes in behind him.

The note makes its way to the desk of Jasper, a seasoned ‘dead letter’ investigator at a 1980s midwestern post office.

As he begins to piece together the letter’s origins, it leads him down a violent, unforeseen path to a kidnapped keyboard engineer and his eccentric business associate. Watch the trailer.

Series. The new season sees DI Max Arnold (Adrian Scarborough) and DS Layla Walsh (Vanessa Emme) delve once more into the darker side of Chelsea that lurks beneath its glossy façade.

Season 3 finds Max and Layla investigating the discovery of an ex-soldier’s body in an allotment, the brutal murder of an antiques dealer, and the mysterious case of a climate scientist found dead in a stolen car. But, while Max remains adept at solving crimes, things are far from straightforward at home.

Film (2025). When several of his fellow Vatican exorcists are simultaneously killed, Father Mason Harper returns to his childhood home to spend time with childhood friend while he awaits orders from the Church.

Ernest Hemingway is often considered to be one of the greatest American novelists of all-time. His novels, including The Old Man and the Sea, A Farewell to Arms, and For Whom the Bell Tolls, are studied in schools and universities across the world. Bautista didn’t discuss his love for Hemingway’s work. Instead, he is fascinated by Ernest Hemingway’s elder years. “Later in his life, he was just dark, and it was mysterious, it was intriguing,” he said, continuing:

“I thought, ‘Man, this is a character. I could really just dive into this.’ And this would be the type of role that would get me in those conversations where they would really see me as a great actor. I still have that chip on my shoulder, wanting to prove that. And I haven’t been able to find that particular role or that particular character where I can prove that.”

Dave Bautista’s dream Ernest Hemingway biopic hasn’t been officially picked up by any studio. Before that dream comes true, Dave Bautista is still shifting between genres. He currently stars in Paul W.S. Anderson’s fantasy/western, In the Lost Lands, based on the novel by George R.R. Martin.

Source: Polygon

10 Nobel Prize-Winning Books That Deserve a Permanent Spot on Your Shelf (Picture Credit – Instagram)

This novella tells the poignant tale of an ageing fisherman, Santiago, who battles a giant marlin in the open sea. Hemingway’s stark yet poetic writing style captures themes of resilience, isolation, and the unyielding spirit of man. A short read, ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ is a literary gem that lingers in the mind long after the final page. Through its deceptively simple story, Hemingway explores the quiet dignity of struggle, making this book an essential addition to any bookshelf