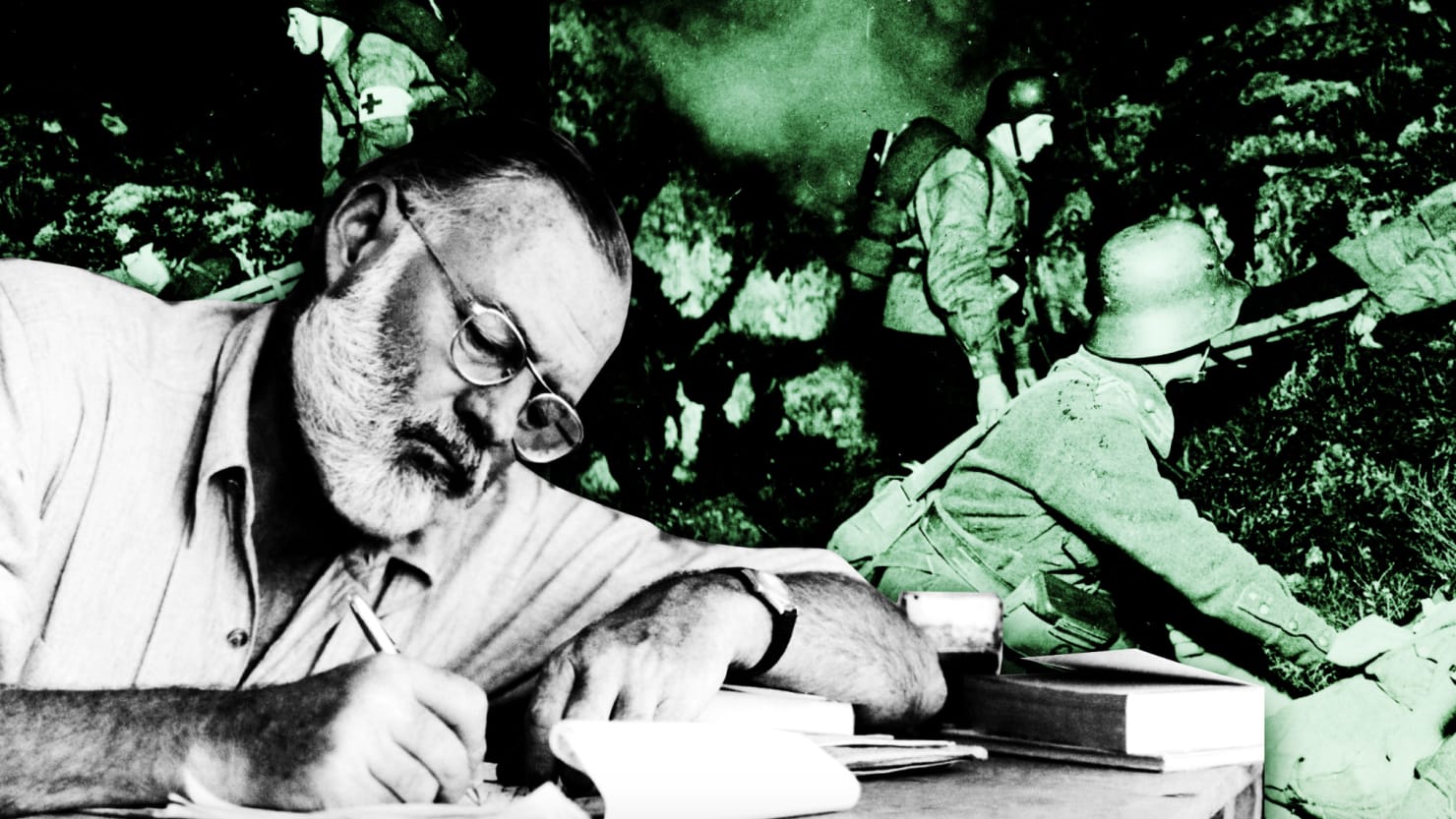

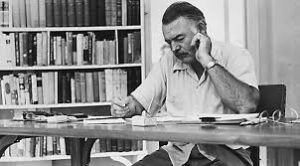

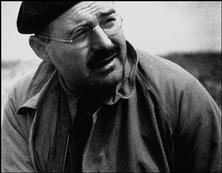

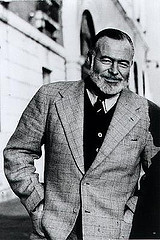

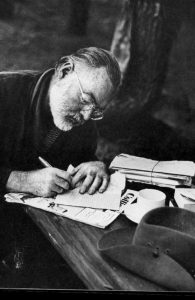

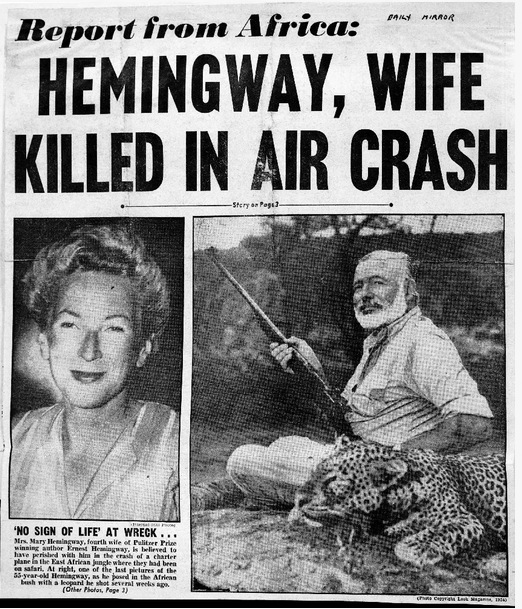

Please read the NYT review of Hemingway’s Masterpiece and how it was received in its Day. And the reviewer taught at my Alma Mater. Media added by me. Enjoy the analysis and thank you for reading and being interested in Hemingway 119 years after his birth and 57 years after his death. Best, Christine

September 7, 1952

Hemingway’s Tragic Fisherman

By ROBERT GORHAM DAVIS

THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA

By Ernest Hemingway.

The “Old Man” is a Cuban, without money to buy proper gear or even food, and past the days of his greatest strength, when he was “El CampÈon” of the docks. He fishes for his living, far out in the Gulf Stream, in a skiff with patched sails. It is September, the month of hurricanes and of the biggest fish. After eighty-four luckless days a marlin strikes his bait a hundred fathoms below the boat. The old man, Santiago, is “fast to the biggest fish that he had ever seen and bigger than he had ever heard of.” The ultimate is now demanded of the craft which a half-century of fishing has taught him.

It is a tale superbly told and in the telling Ernest Hemingway uses all the craft his hard, disciplined trying over so many years has given him. Both craft–writing and fishing–are clearly in mind when the old man Santiago thinks of the strangeness of his powers as fisherman. “The thousand times that he had proved it meant nothing. Now he was proving it again. Each time was a new time and he never thought about the past when he was doing it.” When the boy who took care of him asked if he was strong enough now for a truly big fish, he said, “I think so. And there are many tricks.”

In “Big Two-Hearted River,” one of the best and happiest of his early short stories, Hemingway sent a young man very like himself off alone on a fishing trip in completely deserted country in northern Michigan. They young man, Nick, needed to be alone and to control his thinking with physical tiredness and to get back to something in himself to which memories of fishing seemed to offer a clue.

The actual fishing was even better than his memories of it. He “felt all the old feeling.” The trip was a success because Nick, grateful for the purity of his pleasure, was able to set himself limits. He did not go into the deep water of the swamp where the biggest fish were, but where it might be impossible to land them. “In the fast deep water, in the half light, the fishing would be tragic. In the swamp fishing was a tragic adventure. Nick did not want it.” There was plenty of time for that kind of fishing in the days to come.

“The Old Man and the Sea” written more than twenty-five years later, in the maturity of Hemingway’s art, is a novella whose action is directly, cleanly and, as he would say, “truly” told. And in it Hemingway has described a fishing adventure which is tragic, or as close to tragedy as fishing may be. In “The Old Man and the Sea,” as in the early “Big Two-Hearted River,” the art and the truth come from a sense of limits. In the new story, however, a man exceeds the limits, and pays a price for it that is more than his own suffering.

The line of dramatic action in “The Old Man and the Sea” curves up and down with a classic purity of design to delight the makers of textbooks. But what Santiago brings back suggests something new about Hemingway himself, defines an attitude never so clearly present in his other work.

Hemingway’s heroes have nearly always been defeated, or have died, and have lost what they loved, even though the stories seemed at first to celebrate purely physical courage and prowess. The important thing was the code fought by, and keeping the right feeling toward what was fought for, and when something had been won, not to let the sharks have it.

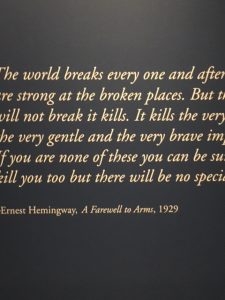

Usually the hero has been alone in his defeat, like Lieutenant Henry in “Farewell to Arms,” walking back to his hotel in the rain, or Robert Jordan dying at the bridge in “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” or Harry Morgan, also a Gulf fisherman, in “To Have and Have Not,” gasping out, with a bullet through his stomach, “One man alone ain’t got no bloody. . .chance.”

Often his people have been profoundly bitter in defeat, like Belmonte, the matador, in “The Sun Also Rises,” sick with a fistula, jeered at by the crowd, putting his head on the barrera, not seeing or hearing anything, just going through his pain, or the demoted Colonel Cantwell in “Across the River and into the Trees,” trying to find abusive enough epithets for Truman and the political generals and a writer whose face he doesn’t like. “Seems like when they get started they don’t leave a guy nothing,” the boy says at the end of “My Old Man.”

This is the nothingness, the “nada” of the famous parody of the Lord’s Prayer in “A Clean Well-Lighted Place.” This is the world of the non-religious existentialists like Heidegger and Sartre, a world of self-imposed codes and devotions sustained wholly by the courage and will of the individual, by his capacity for facing his own truths, for leading an “authentic” existence. If he fails, he encounters nothingness, meaninglessness, both in human society and the indifferent realm of nature.

In “The Old Man and the Sea,” it is all quite different. The old man has learned humility, which he knew “was not disgraceful, and carried no less of true pride.” Humility understands the limits of what a man can do alone, and knows how much his being, the worth and humanity of his being, depends on community with other men and with nature, which is here the sea. Santiago has the language to express this, as the American Harry Morgan did not. Santiago speaks in those formalized idioms from the Romance languages which in so many of Hemingway’s stories have served to express ideas of dignity, propriety and love. Santiago lives in a good town where he had been happy with his wife, and where there is now the boy. He had taught the boy fishing, and the boy loves him. “QuÈ va,” the boy says devotedly. “There are many good fishermen and some great ones. But there is only you.”

Hemingway we know was himself a champion, a great winner of boxing matches and game fishing contests at Key West and in the Bahamas in the Thirties. But in the later stories, in an uncomfortably personal way, it seemed not enough for the hero to know he was a champion. He needed adulation from those around him, from waiters, people of old families and especially sexually satisfied women who had so little being apart from him that they created none of the moral demands, the difficult ups and downs of any normal human relationship.

It is a little like this with Santiago and the boy, but the old man, to repeat, has humility, and the shared craft of fishing is a reality between them. What he brings back to the boy at the end of the story implies a human continuity and development that far transcends this individual relationship. When Santiago says “Man is not made for defeat,” he is not thinking primarily of the individual.

Even without the boy Santiago is not alone on a sea, which, with its creatures, he knows well and loves with discrimination. The sea is feminine for him, as it is not for the motorboat men. The Gulf Stream takes him out where he wants to go, and the trade winds bring him back, with lights of Havana to guide him. When the huge marlin strikes, he is bound in shared suffering with a fellow creature for whom he finds adjectives like “calm” and “beautiful” and “noble.” Santiago does not like to kill, and he does like to think, except about sin, which he is not sure he believes in.

Santiago’s simplicity together with the articulateness of his soliloquies sometimes makes him seem a personified attitude of his complex creator rather than a concrete personality in his own right. The action is wonderfully particularized, but not the man to whom it happens and who gives it meaning. The talk of baseball, of the “great DiMaggio” and the “Tigres” of Detroit does not help in this. And the references to sin inevitably recall that other American story of the pursuit of a big fish in which Melville went rather more deeply down among “the strong, troubled, murderous thinkings of the masculine sea,” that dark invisible sphere formed “in fright” as well as love.

But these are simply the bounds rather than the faults of a short tale magnificently told. Like “Across the River and into the Trees,” “The Old Man and the Sea” (a September Book-of-the-Month dual choice) is an interruption in the long major work which has engaged Hemingway since the war. But it is not a disturbing interruption, as “Across the River” sometimes was in its moments of tastelessness and spleen. In his imagination of the fishing in “The Old Man and the Sea,” Hemingway has, like the young man in “Big Two-Hearted River,” got back to something good and true in himself, that has always been there. And with it are new indications of humility and maturity and a deeper sense of being at home in life which promise well for the novel in the making. Hemingway is still a great writer, with the strength and craft and courage to go far out, and perhaps even far down, for the truly big ones.

Mr. Davis, Professor of English at Smith College, writes frequently of the techniques of creative writing.

![Night at Key West (A Simon Wolfe Mystery Book 1) by [Hart, Craig A.]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51PMi1RDz2L.jpg)