The story continues:

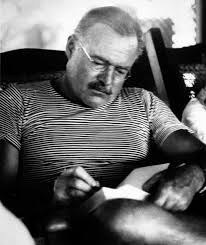

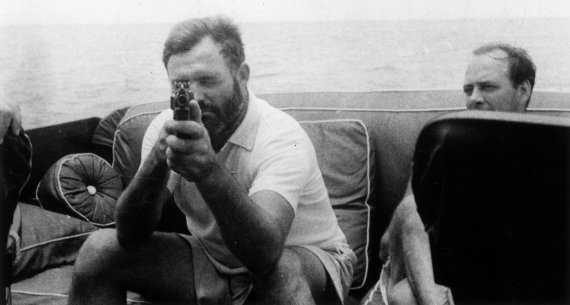

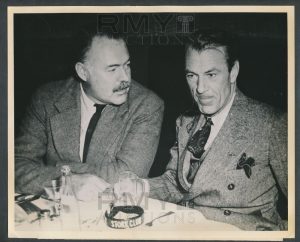

When Gary Cooper became embroiled in a torrid love affair with Patricia Neal—somewhat ironically—Hemingway was the one he talked to about it and the much married Hemingway encouraged him to return to his wife and family. Eventually Cooper did.

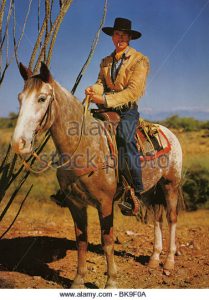

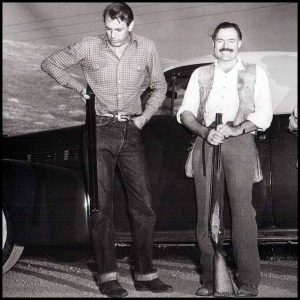

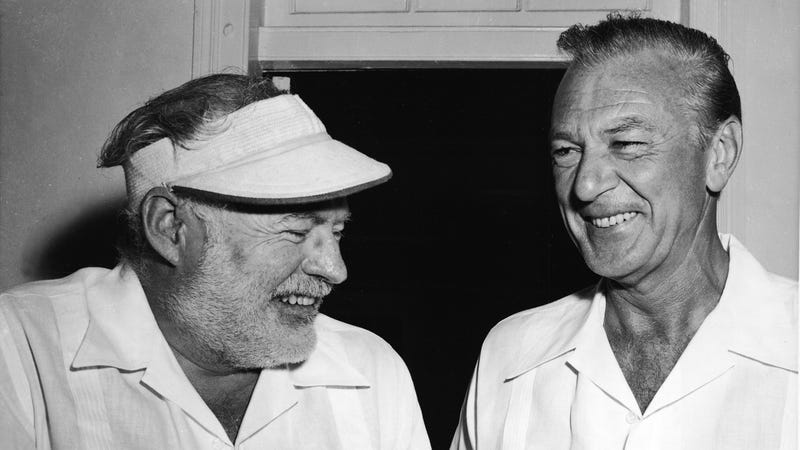

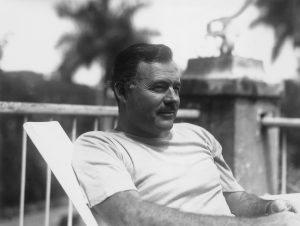

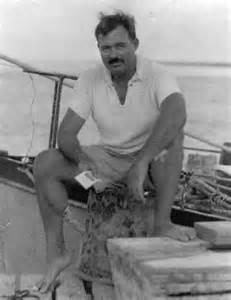

Hem and Gary fished and rode together; Hemingway was always pulling a cigarette away from Cooper telling him they were going to kill him; Cooper was very close to Hemingway’s son Jack; Hemingway and Cooper both went into eclipse at roughly the same time, i.e. from 1945 to perhaps 1950 and then came roaring back strong.

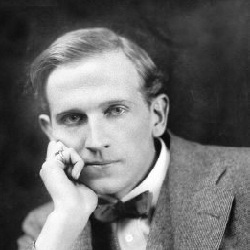

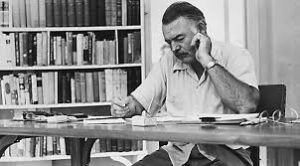

Hemingway came back with The Old Man and the Sea and Cooper came back with High Noon. Cooper was always surprised by Hemingway’s celebrity since it’s rare for a writer to be flocked by fans and Hemingway admired Cooper’s authenticity and the fact that he was far more intellectual than he would let on. It served his purpose to be thought to be the man of few words and “everyman” who rose to heroics on occasion. In fact, he was an intellectual of some depth. When Hemingway was depressed toward the end of the 50s, Cooper tried to find projects that would perk him up such as bringing Across the River and into the Trees and some of the short stories to life in movie or tv form.

When Cooper heard that Hemingway was in two plane crash, he was driving with his daughter Maria and almost swerved off the road, according to Maria.  He was shaken to his core and immediately turned around to get to a phone to find out if there was any more news about his and Mary’s fate. When Jimmy Stewart accepted the academy award for career achievement on Gary Cooper’s behalf in January 1961, he was emotional.

He was shaken to his core and immediately turned around to get to a phone to find out if there was any more news about his and Mary’s fate. When Jimmy Stewart accepted the academy award for career achievement on Gary Cooper’s behalf in January 1961, he was emotional.

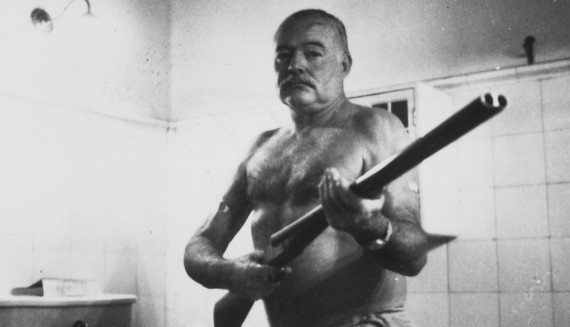

Few knew that Cooper was extremely sick with pancreatic cancer. Gary hid it from all except family for a year. Hemingway was devastated. When Coop called for what both knew was their last call, neither acknowledged the sorrow or the extremis that both were in albeit in different ways. Coop closed by saying, “I bet I’ll beat you to the barn.” Hemingway sunk even lower into despair.

Gary Cooper died of cancer on May 13, 1961. Hemingway was in no condition to attend the funeral. Hadley, Hemingway’s first and most beloved wife, knew something was truly wrong with Hemingway when she read that he did not attend Coop’s funeral. She sent him a note that expressed fear for him and begged him to contact her. He didn’t. Hemingway died by his own hand six weeks later on July 2, 1961.

Condolences rolled in for both of them as if they were heads of state and the impact was felt worldwide. There aren’t many actors or writers who elicit that response today. See “The True Gen.” It’s beautiful.