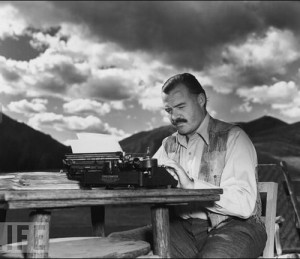

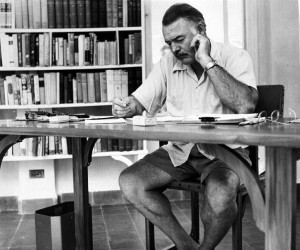

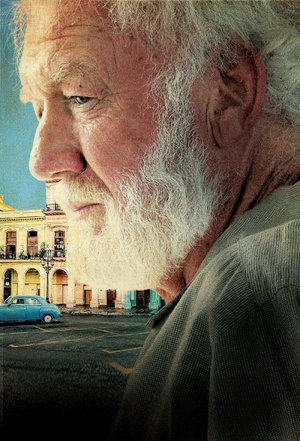

I posted this in January but i read it again last night and it deserves to be posted again. A man after my own heart. Please read. I added some different photos. Best to all, Christine

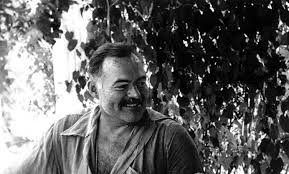

Lessons from Hemingway: A guide to life

Brandon King / Red Dirt Report

Brandon King / Red Dirt ReportYUKON, Okla. — I’m sitting an office surrounded by books I’ve read time after time. Each word, each stanza says something different yet I keep reading.

This is what it must feel like to be religious and captured by something through and through.

Each day, I attempt to write something new and original in hopes to capture the spirit of something yet to be said.

This, and many other lessons, I learned from one of the greatest American writers who ever lived.

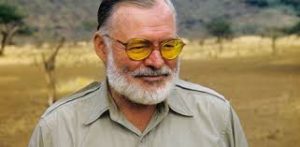

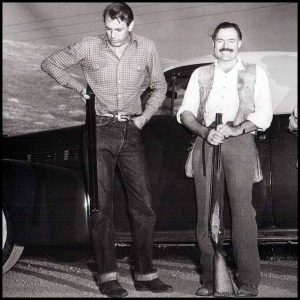

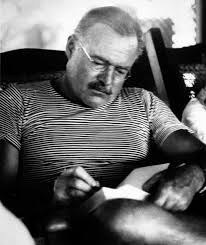

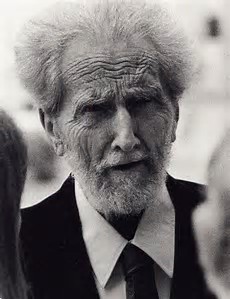

Ernest Hemingway is more than a writer; he is something which doesn’t pass through life often.

Hemingway was a man of originality who cursed clichés and lived as though death bit at his heels. Eventually, he would give up running.

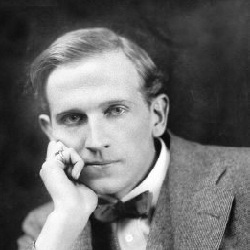

I began reading Hemingway shortly after high school. As an 18-year- old who had grown up in the small, yet growing, town of Yukon, culture was a commodity few and far between. It was as barren as it was lonely. At the time, I was reading pieces from writers like Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot. They were powerful yet they lacked a punch I wanted to read.

It wasn’t until a trip to Half-Price Books which my perspectives would change.

A blue book was fringed on the corners from being dropped too often. In silver letters, it read A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway. As a literary nerd, I had heard the name yet the words and meanings were not there yet.

Since this time, I have read all but two of Hemingway’s pieces. In a near obsessive state, I have found a voice which echoes through the halls of time and continues to speak to those tired of the monotony of modern living.

With each novel and short story, Hemingway provides a lesson for each reader. This should be the goal for any writer worth his or her words. Without meaning, a writer is no more than words on a deaf ear.

Before reading Hemingway’s work, I would find myself asking questions that people could only speculate the answer to. By the time I was finished, I would wonder why I hadn’t thought of that solution before. Though his work deals with death and despair mixed with the feelings of age and war, Hemingway shows us that the world can be seen in any light.

Subjects like love and loss are covered in almost every piece of work. It’s easy to summarize the passing of someone you once loved as painful. It’s quite another thing to express it the way Hemingway did.

For most readers, we all have experienced what it’s like to fall in love with someone and have the hands of death snatch them before their time.

At least I have.

The lessons of Hemingway can give those without a voice a map to find how to express themselves. This is the problem with society as it progresses; just because civilization continues to survive does not mean that civilization grows.

For you, the reader, when was the last time you picked up a novel and read it for what it was worth? When was the last time you enjoyed yourself as you read something so profound that you could feel it touch your heart?

According to the PEW Research Institute, 26 percent of American adults have not read a single book over the past year. This means that no new ideas and possibly no creative endeavor has been established in over a year.

I could list every reason as to why you should learn the lessons of Hemingway but nothing good ever came free. As I’ve learned from Hemingway, “there is no friend as loyal as a book.”

Lessons come by easier for those wanting more out of life. Complacency is a mutual dish that is best served to those who want to survive. For writers and free-thinkers like Hemingway, there is more to life than survival.

It’s the stakes of being original and true. Listed below are the books that have helped me deal with certain issues. If you are interested, please invest in your local library and read on.

To quote Hemingway, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.”

A Farewell to Arms: Depression, death and love

The Sun Also Rises: Masculinity, maturity and adventure

The Old Man and the Sea: Aging, death, trying against all odds

For Whom the Bell Tolls: War, destruction, and courage

A Moveable Feast: Dealing with family, memories, and depression

The Garden of Eden: Skepticism, faith and originality