Part Two of Trivia:

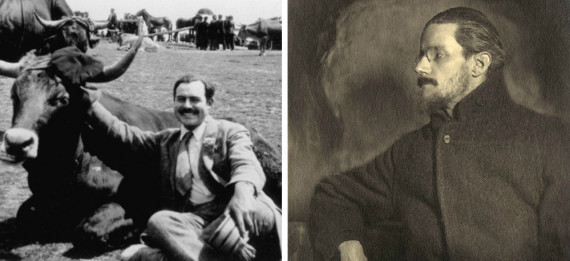

7. James Joyce would get in bar fights and then have Hemingway beat the person up.

Kenneth Schuyler Lynn has a quote in his book, Hemingway, from the novelist about Hemingway and James Joyce’s hangouts together.

“We would go out for a drink,” Hemingway told a reporter for Time magazine in the midfifties, “and Joyce would fall into a fight. He couldn’t even see the man so he’d say: ‘Deal with him, Hemingway! Deal with him!’”

8. According to Hemingway, his eyelids were particularly thin, causing him to always wake at daybreak.

This also comes from the New Yorker profile, where Ross wrote, “He always wakes at daybreak, he explained, because his eyelids are especially thin and his eyes especially sensitive to light.”

Hemingway is then quoted as saying, “I have seen all the sunrises there have been in my life, and that’s half a hundred years.” Hemingway continues, “I wake up in the morning and my mind starts making sentences, and I have to get rid of them fast — talk them or write them down.”

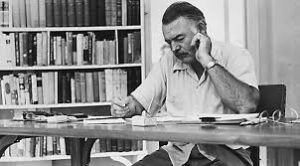

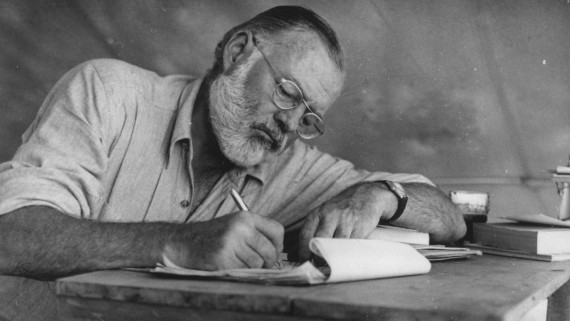

9. His daily word count was tracked on a slab of cardboard on his wall.

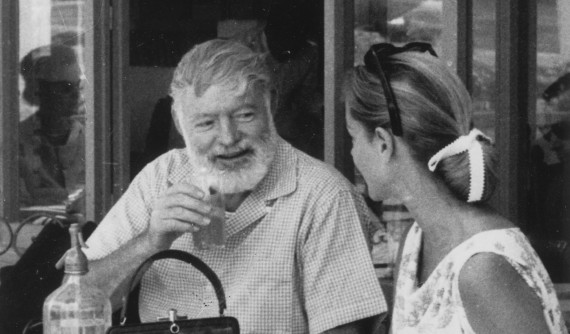

American journalist George Plimpton interviewed Hemingway in a Madrid café during May, 1954. In his piece, Plimton writes:

He keeps track of his daily progress — “so as not to kid myself” — on a large chart made out of the side of a cardboard packing case and set up against the wall under the nose of a mounted gazelle head. The numbers on the chart showing the daily output of words differ from 450, 575, 462, 1250, back to 512, the higher figures on days Hemingway puts in extra work so he won’t feel guilty spending the following day fishing on the Gulf Stream.

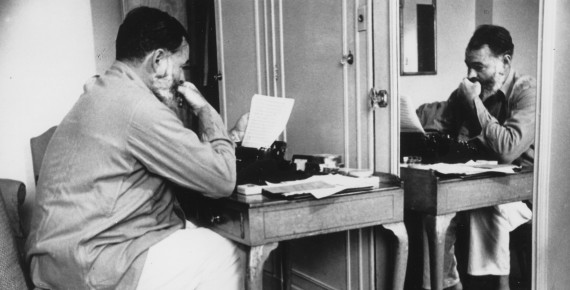

10. The ending of A Farewell to Arms was rewritten 39 times.

Also in the Madrid café in 1954, Plimpton got a quote from Hemingway about rewriting the ending to one of his most famous works.

Plimpton asked how much rewriting Hemingway does, to which the novelist responded, “It depends. I rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, 39 times before I was satisfied.”

The interviewer wondered, “Was there some technical problem there? What was it that had stumped you?”

Hemingway responded, “Getting the words right.”

11. This is how Hemingway said he wanted to spend his older days …

From the New Yorker profile, here is an extended description by Hemingway of how he would have ideally spent his older days:

“What I want to be when I am old is a wise old man who won’t bore,” he said, then paused while the waiter set a plate of asparagus and an artichoke before him and poured the Tavel. Hemingway tasted the wine and gave the waiter a nod. “I’d like to see all the new fighters, horses, ballets, bike riders, dames, bullfighters, painters, airplanes, sons of bitches, café characters, big international whores, restaurants, years of wine, newsreels, and never have to write a line about any of it,” he said. “I’d like to write lots of letters to my friends and get back letters. Would like to be able to make love good until I was eighty-five, the way Clemenceau could. And what I would like to be is not Bernie Baruch. I wouldn’t sit on park benches, although I might go around the park once in a while to feed the pigeons, and also I wouldn’t have any long beard, so there could be an old man didn’t look like Shaw.” He stopped and ran the back of his hand along his beard, and looked around the room reflectively. “Have never met Mr. Shaw,” he said. “Never been to Niagara Falls, either. Anyway, I would take up harness racing. You aren’t up near the top at that until you’re over seventy-five. Then I could get me a good young ball club, maybe, like Mr. Mack. Only I wouldn’t signal with a program—so as to break the pattern. Haven’t figured out yet what I would signal with. And when that’s over, I’ll make the prettiest corpse since Pretty Boy Floyd. Only suckers worry about saving their souls. Who the hell should care about saving his soul when it is a man’s duty to lose it intelligently, the way you would sell a position you were defending, if you could not hold it, as expensively as possible, trying to make it the most expensive position that was ever sold. It isn’t hard to die.” He opened his mouth and laughed, at first soundlessly and then loudly. “No more worries,” he said. With his fingers, he picked up a long spear of asparagus and looked at it without enthusiasm. “It takes a pretty good man to make any sense when he’s dying,” he said.