This is an article by Alexander Fiske-Harrison as published in The Spectator.

Do we really need 17 volumes of letters especially when Hemingway specifically requested in his will that his personal letters not be published?

‘In the years since 1961 Hemingway’s reputation as “the outstanding author since the death of Shakespeare” shrank to the extent that many critics, as well as some fellow writers, felt obliged to go on record that they, and the literary world at large had been bamboozled, somehow.’ So wrote Raymond Carver in the New York Times in 1981. My, how times have changed.

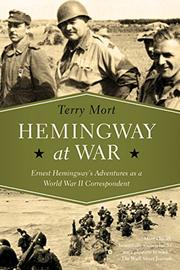

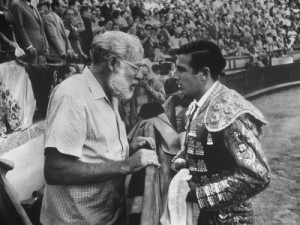

In the past 12 months alone this reviewer has seen Hemingway elegantly caricatured in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris, strut the West End stage thinly disguised as Jake Barnes in an adaptation of his novel The Sun Also Rises (a production on which I was pleasingly credited as ‘bullfighting consultant’), be traduced with neither art nor foundation in Paula McLain’s novel about his first marriage, The Paris Wife, and fascinatingly explicated in the monograph, Beyond Death in the Afternoon by Allen Josephs (who, unlike McLain, knows well the difference between a banderillero and a picador.)

And I wasn’t even in England for most of the year. Orson Welles had it right when he said in his interview with Michael Parkinson in 1974 that although Hemingway ‘was in total eclipse for the last ten years, the sun is rising again critically for him. He’s been dead long enough.’

However, one wonders how long do you have to be dead for, and how good a writer do you have to be, for 17 volumes of collected letters to be too much of a good thing. The first volume begins when the author was seven years old, for Christ’s sake. Indeed, that it is a good thing at all is in serious doubt: in the introduction to this volume Hemingway himself is quoted, from a letter to his executors three years before his death, quite explicitly:

It is my wish that none of the letters written by me during my lifetime shall be published. Accordingly, I hereby request and direct to you not to publish, or consent to the publication by others, of any such letters.

This is followed by some rather sketchy and self-serving argument by the editors — along with his only surviving son, Patrick — that his correspondence is owed to posterity, to scholarship, and that anyway, if he didn’t want them published, he should have burned them. One wonders, in this age of total information, whether just such an argument won’t be used to publish the credit- card statements of, say, Saul Bellow or John Updike, ‘so we can more accurately know the writer as he actually lived, rather than the mask he wrote for himself’. If the academics are after you, God forbid they find your email password after you’re gone.

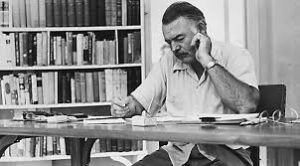

Whatever the rights and wrongs, there is no denying that the letters are of interest, although the interest is necessarily patchy, given the inclusion of everything from financial instructions to stockbrokers to artistic advice to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Scholars will undoubtedly find the minutiae fascinating, while literary gossips will focus on familiar names such as Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford and Gertude Stein.

My own interest was piqued, admittedly, by Hemingway’s discovery of bullfighting and Spain during these years, his reaction to which was the inspiration for my stint as an amateur torero in 2010. So I was intrigued to see quite how little hispanophilia and tauromania impinged on his everyday life and professional thoughts, given what some would have us believe. That a man of an aesthetically sensitive temperament who survived gruesome wounds, psychological and physical, in the first world war should be drawn to the gore of the corrida de toros is not exactly surprising; but those who try to make it central to Hemingway’s intellectual development will be disappointed by this evidence. As A Moveable Feast made clear, someone like Pound, who impressed so hard on his protégé a combination of minimalism and le mot juste, was far more important to the development of Hemingway’s mid-1920s style of ‘omission’ than his infrequent, though devout, hero-worship of matadores including Juan Belmonte, El Niño de la Palma and Maera.

However developmentally intriguing such speculations may be, one still has to ask oneself why one is reading someone’s letters without their permission in the first place. In Hemingway’s case it could be because he developed a style within his métier as powerful, innovative and influential as, say Marlon Brando’s in acting or, indeed, Belmonte’s in toreo. But this is the very thing that is not in the letters. Apart from a few flashes of distinctly mannered rhythms, the style is warmly unpretentious and frequently playful.

However developmentally intriguing such speculations may be, one still has to ask oneself why one is reading someone’s letters without their permission in the first place. In Hemingway’s case it could be because he developed a style within his métier as powerful, innovative and influential as, say Marlon Brando’s in acting or, indeed, Belmonte’s in toreo. But this is the very thing that is not in the letters. Apart from a few flashes of distinctly mannered rhythms, the style is warmly unpretentious and frequently playful.

What is most striking is how accurately he assessed his own worth and impact; that if he wrote ‘awfully well’ it would ‘last right on through’. It didn’t just last, but changed literature ever after — although not all would say for the better.

And this is not restricted to literature: in July this year, while participating in my 19th ‘running of the bulls’ in Pamplona, I was tripped and trampled by a rampaging herd of drunken tourists, 5,000 of whom were crowded into the half-mile that comprise the world’s most famous encierro. After I was dragged to safety before a group of bulls could add their weight to the melée, I discovered that my saviour was none other than John Hemingway, Ernest’s grandson. As we later shared a drink, I half-jokingly remarked: ‘You know it’s you Hemingways’ fault that all of us idiots are here in the first place.’ There are more than a few novelists — Norman Mailer and Elmore Leonard spring immediately to mind — who could say the same thing.