Dear Readers: Hemingway still inspires. Best, Christine

THE GOOD SOLDIER

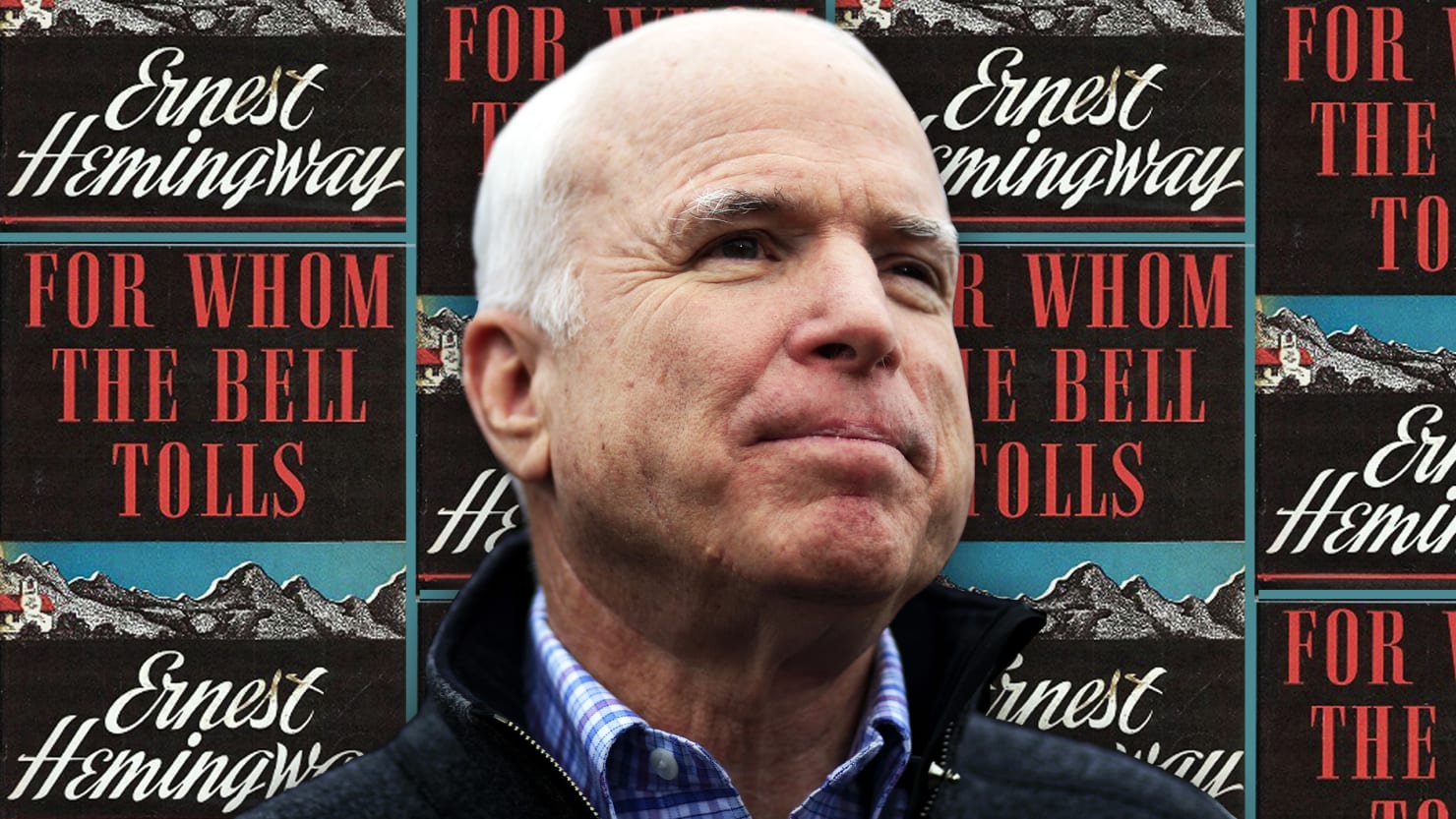

John McCain Found Lifelong Inspiration From a Hemingway Hero

The late senator first read ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ when he was 12 years old, and the book’s hero, Robert Jordan, became an enduring role model.

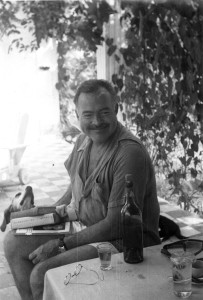

No literary figure, Senator John McCain often pointed out, had more influence on how he conducted his life than Robert Jordan, the hero of Ernest Hemingway’s 1940 novel about the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

In his most recent book, The Restless Wave, written in collaboration with Mark Salter, McCain wrote about his impending death by observing, “’The world is a fine place and worth the fighting for and I hate very much to leave it,’ spoke my hero, Robert Jordan, in For Whom the Bell Tolls. And I do, too. But I don’t have a complaint. Not one.”

McCain first read For Whom the Bell Tolls when he was 12, and he returned to it in succeeding years. “It’s my favorite novel of all time. It instructed me to see the world as it is, with all its corruption and cruelty, and believe it’s worth fighting for anyway, even dying for,” McCain observed earlier this year in an interview. The title of McCain’s 2002 memoir, Worth Fighting For, comes from the same For Whom the Bell Tolls passage that he quotes in The Restless Wave.

With so many literary heroes to pick from, McCain’s choice of Robert Jordan is revealing. Robert Jordan is no superhero, capable of overcoming all odds. Even in the 1943 movie version of For Whom the Bell Tolls, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, Jordan dies alone. In the passage McCain cites in The Restless Wave, Jordan lies concealed behind a tree with a submachine gun, hoping he can delay the heavily armed fascist troops who have been pursuing him and the guerrilla band he is with.

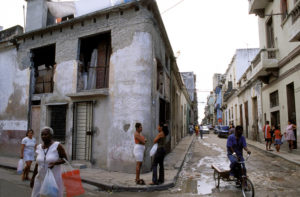

Jordan has gotten himself into this position by traveling from America to Spain to flight with the Loyalist forces supporting the democratically elected government of the five-year-old Spanish Republic, which in 1936 came under siege from a fascist military coalition led by General Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain from the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939 until he died in 1975.

Jordan knows that his own death is a certainty. He has sustained a broken leg as a result of the horse he has been riding falling on him. No matter what he does, he cannot flee. The best that he can do is sacrifice his life so that others, including the woman he loves, may live. “You’ve had as good a life as anyone because of these last days,” Jordan tells himself. “You do not want to complain because you have been so lucky.”

As he faces the end of his life, Jordan’s bravery reflects his character, but just as important are the choices that have brought him to this point. He is not a professional soldier, although he comes from a family in which his grandfather fought in the Civil War for four years. Until now Jordan has led a quiet life as an instructor in Spanish at the University of Montana. As a child he saw a lynching, but he was too young to do anything about it.

What has led Jordan to abandon the comfortable life he was leading in America is the prospect of the Loyalist defenders of the Spanish Republic being overwhelmed by a fascist cabal relying on foreign aid. During the Spanish Civil War, America was neutral as a result of a bill President Roosevelt signed on May 1, 1937, banning the export of arms and ammunition to the warring parties in Spain.

By contrast, neither Germany nor Italy saw any reason to remain neutral when they believed they had much to gain from helping a fascist ally. As historian Adam Hochschild notes in Spain Is in Our Hearts, his account of the Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War, the German and Italian contributions to Franco were immense and gave both nations a chance to test out weapons they would use in World War II.

Some 19,000 German troops and instructors saw action in Spain or helped train Fascist troops, and nearly 80,000 Italian troops fought for Franco between the start of the Spanish Civil War and its conclusion. The Soviet Union, which for a period identified itself with the Loyalists, provided only limited aid by comparison.

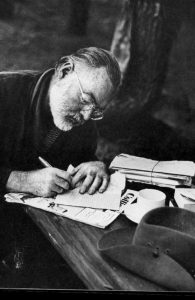

For Hemingway, who made four trips to Spain to report on its Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance, Jordan was an admirable figure who reflected what was best about the 2,800 Americans who went to Spain to fight on the Loyalist side. Jordan knows that the Loyalist side he is on is capable of great cruelty. He is no fan of the Communists who are part of the Loyalist alliance. But Jordan sees the flaws in the fascists as so much greater than those of the Loyalists that he does not back away from the commitment he has made to the war.

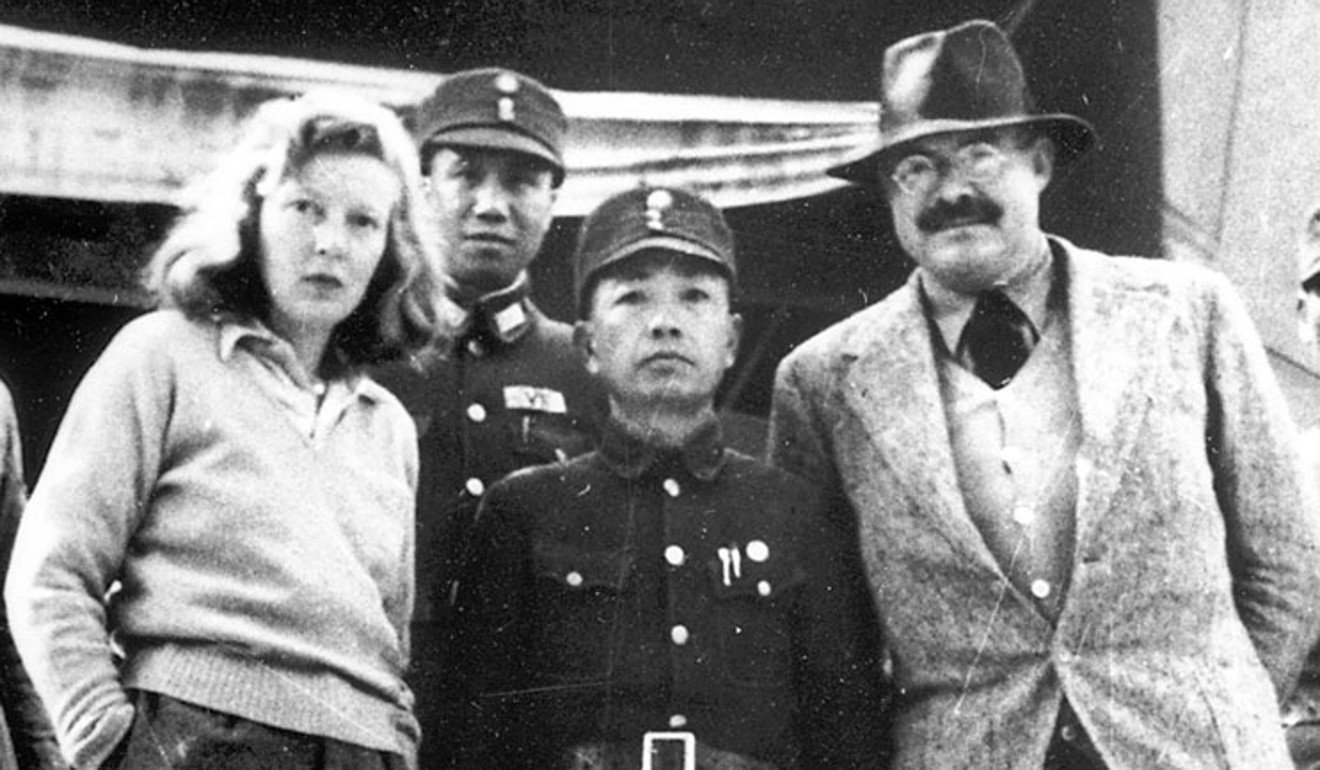

In this commitment Jordan mirrors Hemingway, who in a 1937 letter described the Spanish Civil War as “the dress rehearsal for the inevitable European war.” Hemingway raised money in support of the Loyalist side, and with his future wife, the correspondent Martha Gellhorn, who travelled to Spain with him, he went to the White House for a showing of the pro-Loyalist film, The Spanish Earth, before President and Eleanor Roosevelt.

In the end Hemingway had to content himself with doing his best rather than getting the outcome in Spain that he wanted, and so finally must Robert Jordan. What makes Jordan admirable is what made McCain admirable—his unwillingness to sit on the sidelines and watch democracy be undermined.