British publisher Tom Maschler, who conceived the coveted Booker Prize, dies at 87

His crowning achievement arguably came in 1969, when he persuaded sugar trading firm Booker-McConnell to establish a literary prize to rival the French Prix Goncourt. The award, given annually, was later called the Man Booker Prize and is now known as the Booker Prize.The New York Times October 24, 2020 10:58:10 IST

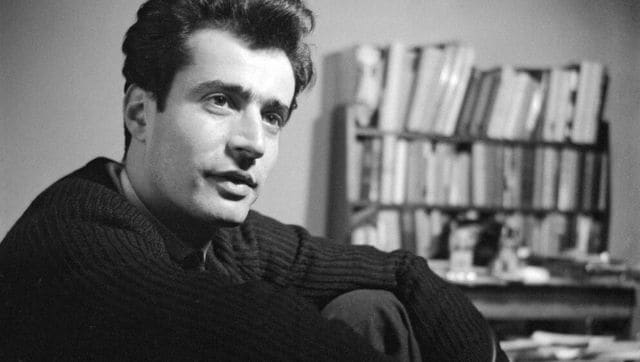

At 26, Tom Maschler was made literary director of Jonathan Cape and catapulted to fame when he acquired the British rights to Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. Image via Twitter

By Sam Roberts

Tom Maschler, the swashbuckling British publisher who fostered the literary careers of more than a dozen Nobel laureates and conceived the coveted Booker Prize to promote fiction, died on 15 October in a hospital near his home in Luberon, in southeastern France. He was 87.

A Jewish refugee from Nazi-occupied Vienna, where his father was a publisher, Maschler was 26 in 1960 when he was named literary director of Jonathan Cape, the prominent London publishing firm, a month after the death of its founder.

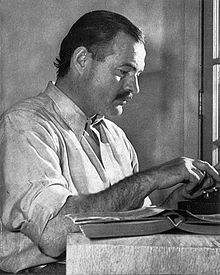

He catapulted to early fame by buying the British rights to Joseph Heller’s debut novel, Catch-22, for a bargain 250 pounds in 1961 (the equivalent of about $700 then and about $6,500 today), and, the next year, by transplanting himself to Idaho shortly after the suicide of Ernest Hemingway to help Hemingway’s widow, Mary, prepare the novelist’s memoir A Moveable Feast for publication.

He also published or nurtured Martin Amis, Jeffrey Archer, Julian Barnes, Bruce Chatwin, Roald Dahl, John Fowles, Clive James, Ian McEwan, Edna O’Brien, Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth and Kurt Vonnegut.

Neither he nor his critics considered him a scholar. He was rejected by the University of Oxford when he applied as an English major. He admitted to being a labored writer. His memoir, Publisher (2005), was widely mocked by reviewers, including one who concluded that it established Maschler’s mantra as “When in doubt, claim credit.”

But no one disputed that the splashy Maschler, who had lived largely by his own wits since he was 12, had jolted the clubby British publishing world with his discerning eye for fiction and his Barnumesque promotional ingenuity.

He acquired a collection of writings and doodles by John Lennon and published them in two volumes, In His Own Write in 1964 and A Spaniard in the Works in 1965. In 1983 he published one of the first pop-up books, The Human Body, by Jonathan Miller.

He decided to publish an early manuscript attributed to an author named Virginia Stephen, before he was informed that it was the maiden name of Virginia Woolf.

And after overhearing Desmond Morris, a zoologist, drop the phrase at a cocktail party, he commissioned Morris to write The Naked Ape (1967), a biological perspective on human behavior that became a bestseller. He later recalled counseling Morris, “If you turn this into a book, it’ll be so successful you’ll never again be taken seriously by scientists, but you’ll be very rich.”

His crowning achievement arguably came in 1969, when he persuaded sugar trading firm Booker-McConnell to establish a literary prize to rival the French Prix Goncourt. The award, given annually, was later called the Man Booker Prize and is now known as the Booker Prize.

“The Booker may be the most important thing I’ve ever done,” Maschler told The Guardian in 2005. “It certainly had an impact, and if it means people think they should occasionally read a good novel, that is something I’m very proud of.”

Thomas Michael Maschler was born on 16 August, 1933, in Berlin to Kurt Maschler, a successful publisher’s representative who later became a publisher himself, and Rita (Lechner) Maschler.

Failing to gain passage to Sweden, where they had hoped to proceed to America, Tom and his mother moved to Britain. (His parents had separated by then.) His mother took a housekeeping job on a country estate while he attended a Quaker school.

When he was 12, he was sent to Brittany to learn French. Shortly after that he won a summer scholarship to a kibbutz in Israel, which he was able to reach only after he had audaciously written David Ben Gurion, the Israeli prime minister, asking him to intercede on his behalf.

Maschler was admitted to Oxford to study philosophy, politics and economics (but not English). He rejected the offer after he learned that he had been accepted because of his prowess at tennis.

Instead he traveled to the United States, where he worked in a tuna cannery, was detained for hitchhiking and wrote travel articles for the Los Angeles Times and The New York Times (for which in 1952, at the age of 19, he chronicled a sojourn that had begun when he arrived in New York that year with $13).

He returned to Europe and, after succeeding as a tour guide in Britain and failing as a film director in Italy, entered publishing in 1955 as a production assistant at André Deutsch. He moved to MacGibbon & Kee, to Penguin and finally to Cape, where he was chair from 1970 until the company was bought by Random House in 1991.

Maschler’s survivors include his wife, Regina (Kulinicz) Maschler, whom he married in 1988; three children, Ben, Hannah and Alice, from his first marriage, to Fay Coventry; and several grandchildren.

Maschler, who hopscotched between homes in London, Wales, France and Mexico, was “more admired than liked,” as The Guardian put it. Publisher Patrick Janson-Smith called him “a tainted genius with the gift of being a stranger to self-doubt.”

Asked by The Japan Times in 2008 whether he believed in himself, Maschler replied: “Yes, I believe in myself. I am not necessarily better than other people, but I know I am different from other people. Correct?”

“Yes, yes,” his press agent replied obligingly.

“Actually,” Maschler added with a laugh, “I think I am better as well.”

Sam Roberts c.2020 The New York Times Company

Updated Date: October 24, 2020 10:58:10 IST

TAGS:

Nice post – interesting and informative