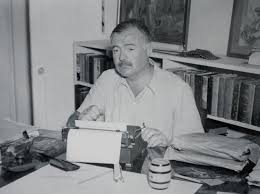

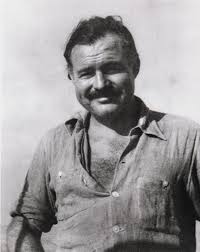

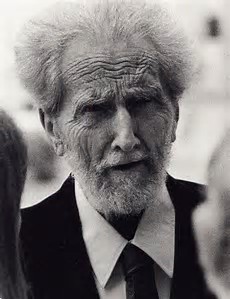

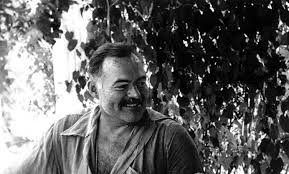

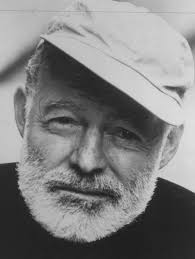

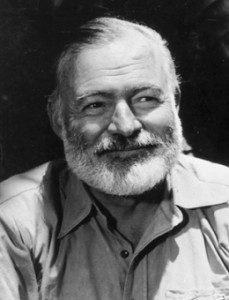

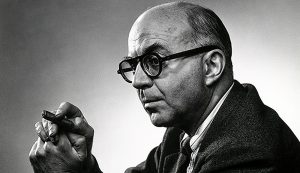

Ernest Hemingway meets the press at his Cuban home on Oct. 28, 1954, after the announcement that the American author was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. (AP file)

In one of Ernest Hemingway’s first published stories, a man goes into the woods and meets a disfigured prizefighter — insightful, though prone to fits of paranoia and violence.

“You’re all right,” says the visitor after they’ve chatted a while.

“No, I’m not. I’m crazy,” the fighter says. “Listen, you ever been crazy?”

“No. How does it get you?”

“I don’t know. When you got it you don’t know about it.”

Nearly a century after “The Battler” was written, psychiatrist Andrew Farah contends, we would recognize that the prizefighter suffered from chronic traumatic encephalopathy or CTE — the same concussion-induced brain disease now infamous in sports, particularly professional football.

And the prizefighter’s renowned author had CTE, too, Farah argues in his new book, “Hemingway’s Brain.”

The psychiatrist from High Point University in North Carolina writes of nine serious blows to Hemingway’s head — from explosions to a plane crash — that were a prelude to his decline into abusive rages, “paranoia with specific and elaborate delusions” and the final violence of his suicide in 1961.

Hemingway’s bizarre behavior in his latter years (he rehearsed his death by gunshot in front of dinner guests, for example) has been blamed on iron deficiency, bipolar disorder, attention-seeking and any number of other problems.

After researching the writer’s letters, books and hospital visits, Farah is convinced that Hemingway had dementia — made worse by alcoholism and other maladies, but dominated by CTE, the improper treatment of which likely hastened his death.

[In stunning admission, NFL official affirms link between football and CTE]

“He truly is a textbook case,” Farah told The Washington Post. “His biography makes perfect sense to me in the context of multiple brain injuries.”

Farah is not the only person to make the link. A shorter discussion of head trauma in Paul Hendrickson’s biography, “Hemingway’s Boat,” convinced a reviewer that the famous writer “was probably suffering from organic brain damage.”

But Farah’s book goes deeper, mixing biography, literature and medical analysis in what he writes is “a forensic psychiatric examination of his very brain cells — the stressors, traumas, chemical insults, and biological changes — that killed a world-famous literary genius.”

Farah dates Hemingway’s first known concussion to World War I, several years before he wrote his short story, “The Battler.”

A bomb exploded about three feet from his teenage frame.

Another likely concussion came in 1928, when Hemingway yanked what he thought was a toilet chain and brought a skylight crashing down on him — causing what Farah describes as “giddy concussive ramblings … about his own blood’s smell and taste.”

Then came a car accident in London — then more injuries as a reporter during World War II, when a German antitank gun blew Hemingway into a ditch.

The psychiatrist describes his reported symptoms: double vision, memory trouble, slowed thought. And headaches that “used to come in flashes like battery fire,” Hemingway wrote in a letter.

“There was a main permanent one all the time. I nicknamed it the MLR 2(main line of resistance) and just accepted that I had it.”

[The quiet tragedy of Ernest Hemingway]

These were “classic and typical” symptoms of head trauma, Farah writes.

And not the last Hemingway would suffer.

After the war: another car accident. Then a fall on his boat “Pilar,” two years before he published “The Old Man and the Sea,” which a book reviewer called Hemingway’s “last generally admired book.”

Farah did not include in his list of concussions Hemingway’s flirtations with boxing, or accounts of head injuries he could not verify or which he suspected were the author’s tall tales.

But by the time Hemingway survived two consecutive plane crashes on a 1954 safari trip — escaping the second wreck by “batter[ing] open the jammed door with his head,” Farah writes — his remarkable brain was beyond repair.

“The injuries from earlier blows resolved, but, with additional assaults, his brain developed CTE,” Farah writes.

Often — though not always — caused by concussions, chronic traumatic encephalopathy is a degenerative brain disease that can manifest as memory loss, anger, dementia and suicidal behavior — usually decades after the head blow, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Unknown in Hemingway’s day, it has been found in the brains of at least 17 dead athletes, and researchers will look for it in the brain of Aaron Hernandez, a former NFL star who killed himself in prison last week while serving a murder sentence.

Less bizarre but perhaps more devastating to the author: his deteriorating ability to arrange words.

“The genius who had written masterpieces such as ‘A Farewell to Arms’ and ‘The Snows of Kilimanjaro’ was now paralyzed, fully in the grip of a severe mental illness” as he struggled to assemble simple sentences for his memoirs in 1961, Farah writes.

“Only an autopsy can put the 100 percent stamp of approval” on a diagnosis, Farah acknowledged to The Post. But he didn’t back down from his conclusions in the book. “The symptoms are just so obvious,” he said.

CTE accounted for about three-quarters of Hemingway’s dementia, Farah said. “The concussions, alcohol, hypertension, and pre-diabetes all contributed to the changes in Hemingway’s brain,” he writes in his book.

And a long history of suicide in Hemingway’s family couldn’t have helped the author cope with his condition, Farah said.

But he is sure that by the end of his life, Hemingway had concussion-driven dementia, not psychotic depression as his doctors believed — to tragic consequences, he writes.

But depression was not Hemingway’s main problem, Farah argues. The traumas and resulting CTE had physically changed his brain — demented and weakened it.

After a round of shock treatments in early 1961, Farah writes, Hemingway “grew more and more abusive to” his wife, “berating her because of his paranoia.”

She and some friends had to physically restrain Hemingway from shooting himself that April.

He went back to the hospital for more shock treatments.

A few days after being discharged a second time, on July 2, 1961, Hemingway woke before sunrise. He fetched his shotgun from the basement, this time with no one to stop him.

“All his vulnerabilities coalesced in one final instant,” as Farah puts it.

Had he lived in the 21st century, Farah writes, Hemingway would have had an MRI scan, which might have revealed his much-abused brain was shrinking.

He would have been sent to a therapist, and told to stop drinking, to focus on his health, and “remind himself he is safe.”

He likely would have been prescribed antidepressants and vitamin B pills, and kept clear of stresses such as electric current.

Modern medicine could have saved Hemingway’s life, Farah said.

Even if not: “We would have at least understood him.”

“Hemingway’s Brain” by Andrew Farah was published in April 2017 by the University of South Carolina Press.