Dear Readers: May I please call your attention to my friend Curtis DeBerg’s new book which explores and challenges some Hemingway history. The book particularly delves into Hemingway’s time in WWI on the Italian front and the injuries he received. you think you know all of this but maybe not. Curt’s research has developed a new factual analysis of what has been written by many about this time period. Please check it out and see what you think! Best, Christine

Author: Christine Whitehead

Nine Lives Mr. Hemingway?

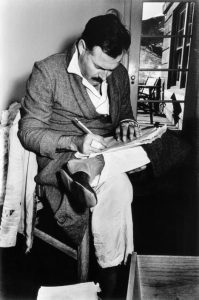

Ernest Hemingway survived anthrax, malaria, pneumonia, skin cancer, hepatitis, diabetes, two plane crashes (on consecutive days), a ruptured kidney, a ruptured spleen, a ruptured liver, a crushed vertebra, a fractured skull, and more.

In the end, the only thing that could kill Hemingway it would seem, was himself…

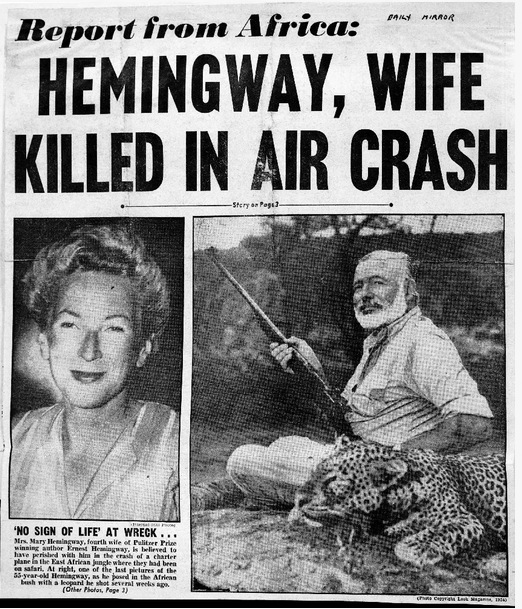

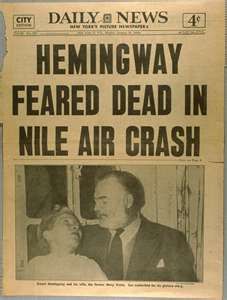

On a trip to Africa in 1954, Hemingway and Mary were in not one but two plane crashes. Both were bad but the second was worse. I’ll write a post on that incident soon. However, it was fear both Hem and Mary died. He delighted in reading the obits about himself. However, there was nothing funny about the wounds he received which lasted the rest of his life. He was always accident prone and had suffered several concussions before the crashes. It was very bad. The below is one of the many new headlines proclaiming the fear that he had perished in the crash. By the way, I hate the game hunting and take some solace in the fact that later in life he had regrets and noted that he preferred shooting wildlife with a camera, not a gun. Best, Christine

In 1954, while in Africa, Hemingway was almost fatally injured in two successive plane crashes. He chartered a sightseeing flight over the Belgian Congo as a Christmas present to Mary. On their way to photograph Murchison Falls from the air, the plane struck an abandoned utility pole and “crash landed in heavy brush.” Hemingway’s injuries included a head wound, while his wife Mary broke two ribs. The next day, attempting to reach medical care in Entebbe, they boarded a second plane that exploded at take-off, with Hemingway suffering burns and another concussion, this one serious enough to cause leaking of cerebral fluid. They eventually arrived in Entebbe to find reporters covering the story of Hemingway’s death. He briefed the reporters and spent the next few weeks recuperating and reading his erroneous obituaries.

!0 Women: Part 2

Sylvia Beach was a facilitator of the success of the Lost Generation in 1920s Paris. The bookshop owner and publisher is famous for founding the iconic Shakespeare & Company on the Rue Dupuytren.

Her establishment served as a gathering place and publishing house for many of the expatriate writers in Paris at the time, including James Joyce, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Ernest Hemingway. She specialized in American and English literature, helping to expose writers to a French market. She published their original works, including Joyce’s Ulysses, after being rejected by publishers in the United States and England.

Hemingway was quick to track down the literary hub, becoming a frequent visitor after only a week of being in Paris. Until the shop’s unfortunate closing in 1941 due to Nazi occupation, Hemingway remained in contact with Beach, exchanging letters and even stopping in sometimes to sign his books. In his memoir A Moveable Feast, Hemingway leaves no doubt that Beach and her progressive oasis were key to his success as an up-and-coming writer.[6]

When a young Hemingway was wounded by shrapnel while driving an ambulance during the First World War, he fell in love with his hospital nurse, the beautiful Von Kurowsky. This affair between nurse and patient, as brief as it was, inspired Hemingway in the many years to come, namely by influencing his novel A Farewell to Arms.

The character of Catherine Barkley is based on Von Kurowsky, and the hero, Frederic Henry, is a wounded American soldier, much like Hemingway in his own life. In the story, Catherine nurses Henry, and they eventually fall in love—again, much like Hemingway’s experience–but the tale does not have a happy ending, as Catherine dies in childbirth.

While Agnes and Ernest may not have had such a tragic end, his heart was broken nonetheless. He wrote, “I’ve loved Ag. She’s been my ideal… I forgot all about religion and everything else because I had Ag to worship.”[7]

The Lost Generation and Ernest Hemingway’s Inspiration for ‘The Sun Also Rises’ | PBS

One such example was his novel The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway’s debut novel. It was based upon a trip he and a group of his fellow expatriates took to Pamplona, Spain. Hemingway went with his wife Hadley, a few gentlemen friends, and Lady Duff Twysden. Lady Twysden was going through a messy divorce and having affairs with a couple of said gentlemen’s friends in the traveling party.

What ensued among the bullfights and brunches was a flurry of insults, fights, sexual tension, sordid affairs, and too much alcohol. Hemingway, in the middle of it all and struggling with his first attempt at a novel, absorbed every moment and, in just six weeks, produced a first draft of The Sun Also Rises.

Many members of the party, including Lady Twysden, were not happy with Hemingway’s publication, claiming that it was hardly fiction at all but rather a pages-long gossip column. Lady Twysden and the posse even coined the terms “B.S.” and “A.S.” to stand for “Before Sun” and “After Sun” because of how much their lives changed after Hemingway’s stunt.

As much as they may not have liked the novel, the fact of the matter is that their lives as the Lost Generation were the perfect fodder to launch a timeless and remarkable literary career.[8]

Androgyny and the Dysfunctional Marriage of Ernest Hemingway and Mary Welsh | PBS

Mary Welsh was Hemingway’s fourth and final wife. While she may not have been a riveting muse, like many women in his life, her influence over his life and legacy is no less significant. Much of the Hemingway history we have today can be attributed to her diligence in preserving his legacy in the years following his death.

She and Ernest spent the last 15 years of his life together, traveling to Cuba, Africa, Spain, and beyond, before finally settling in Ketchum, Idaho. During that time, he won the Nobel and Pulitzer Prizes for literature and survived two plane crashes. Through his literary success and declining mental and physical health, Mary was by his side.

She was also present in their home when he committed suicide on July 2, 1961, at the age of 61. Following his death, Mary stewarded his legacy through the publication of his famous memoir, A Moveable Feast, and donated many of his photographs and letters to the John F. Kennedy Library.[9]

1Valerie Hemingway

At 19 years old, she landed a job interviewing the prolific author in Spain with the publication she was working for. The pair instantly hit it off, with Ernest taking a keen interest in the whip-smart young lady who could hold her liquor and take a joke.

Eventually, he hired her as his personal secretary, a position that would prove critical to the posthumous publication of works like A Moveable Feast. She remained a part of his entourage until his death and continued to be a mainstay in the Hemingway family. She collaborated with Hemingway’s widow, Mary Welsh, to piece together his memoir and even married Hemingway’s son Gregory, whom she divorced later.

Valerie has certainly done the Hemingway name honor through her own work as a writer, journalist, speak

10 Women : Part I

OOKS |

10 Women Who Influenced the Manly Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway is one of the most legendary writers to come out of the twentieth century. His no-nonsense prose, acute observation, and Lost Generation skepticism concretize his novels as some of the best in American literature, but his celebrity reputation is perhaps even better well known.

The rough-and-tough writer was notorious for his machismo, upholding traditional masculinity through his boozing, fighting, hunting, fishing, and womanizing. While he may come across as a man’s man, it is impossible to disregard the deep and profound—and perhaps even ironic—influence the women in his life had on him, from birth until death.

10. Grace Hall Hemingway

“My mother is an all-time American bitch. She would make a pack mule shoot himself,” wrote Ernest Hemingway about his mother, Grace Hall Hemingway.

Ernest was the second child of Grace and Dr. Clarence (Ed) Hemingway. He was born on a summer day outside Chicago, Illinois, and his mother lovingly wrote, “The sun shone brightly, and the Robins sang their sweetest songs to welcome the little stranger to this beautiful world.”

Grace was unlike many women of her generation and neighborhood. She originally had a promising career as an opera singer, but abandoned to return to Chicago to marry Ed. She never let anyone forget her former career, however, and continued to let her creativity flow. She taught music, wrote poetry and her own music, and painted. She even brought in more income than her husband, an obstetrician.

As a mother, she made it a point to expose her children to art, music, and travel. In fact, when each of her children turned eleven years old, she took them to Nantucket for a month of seafaring, history, and art. Sometimes, however, her influence over her children broached the extreme. For instance, when Ernest was a child, she dressed him in the same clothing as his elder sister, Marcelline, to pass them off as twins, among other eccentricities.

With such an artistic, progressive, dominant mother figure, how could a child become anything but a troubled novelist?

While we can never know how influential Grace was on her son, Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn, wrote, “Deep in Ernest, due to his mother, going back to the indestructible first memories of childhood, was mistrust and fear of women.”[1]

Martha was Hemingway’s third wife. Professionally, she and her husband were well matched, as she, too, was a successful journalist, war correspondent, and novelist. While they seemed perfectly suited in their love of travel and dedication to their careers, it was these similarities that perhaps drove them apart and challenged Hemingway more than any other marriage.

At the time of their meeting, Hemingway’s marriage to his second wife was coming to an end, and Gellhorn and Hemingway complimented one another. Between both of their work as journalists, as well as his publication of For Whom the Bell Tolls, they were what today’s culture could call a “power couple.”

That is until her career began to outshine his.

Tension had already begun to grow between them as she covered stories around the world, leaving Hemingway at home for weeks or months at a time. He once wrote to her, “Are you a war correspondent, or wife in my bed?”

She answered him by hopping on a ship to Omaha Beach the day after D-Day, leaving Hemingway and his insecurity at home. Perhaps that sense of insecurity is what pushed him onward to even better work.[2]

One of the most well-known names of the Lost Generation is the stylish and eccentric writer and art collector Gertrude Stein. She is perhaps best recognized for hosting salons in the 1920s in Paris at which names like Picasso, Anderson, and Hemingway all attended at one point or another.

To have the patronage of Gertrude Stein was to be on your way to a respectable career in the arts. Her taste was highly respected in literary circles across the world, making her a very influential person. To have her read your novel for critiques or remark upon your art to a paying ear had the potential to change everything.

When Hemingway and his wife, Hadley Richardson, moved to Paris in the early 1920s, he sought out Stein. He was met with a strong and supportive, if not at times contentious, mentor. She helped connect Hemingway to fellow writers and hone his writing style. Ironically, their execution was very different.

Stein was known for her complex, “stream-of-consciousness” style, while Hemingway is famous for his straightforward, simple prose. Despite these differences and their later disagreement over his novel The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway’s name may not be nearly as well-known if not for the launch pad that was Gertrude Stein’s helping hand.

7Hadley Richardson

Hadley Richardson was Hemingway’s first wife, the woman who was by his side as he pursued his career overseas in Paris. The couple met in Chicago and eventually married in Bay Township, Michigan, in September 1921. Months later, the couple moved to Paris, where they would live off and on for the next several years. Their time in Paris, including their travels, fraternization with fellow expatriates, the birth of their son, and Hemingway’s infidelity, would become the inspiration for his posthumously published memoir, A Moveable Feast.

Her influence does not only extend to that single piece of work. In many ways, she remained a ghost by his side his entire life, with Hemingway writing, “I wished I had died before I ever loved anyone but her.” To look deeply into their relationship, in a fashion, she was a mirror of his own darkness, having herself written, “I know how it feels cause I have so very many times wanted to go and couldn’t on account of the mess it’d leave some other people in.”

Further, while it is well-known that Hemingway died of suicide, it is perhaps less well-known that, fifty or so years prior, a young Hadley Richardson had contemplated her own suicide while attending college at Bryn Mawr. In Paris, she was a rock, ever by his side, even as his affair with editor Pauline Pfieffer took place. She was by his side in Pamplona, where he gained his inspiration for his novel The Sun Also Rises. She bore his first child and was one of the last to speak with him before he died.

Hemingway scholars and historians consider Hadley to be Hemingway’s “favorite wife” or “greatest love,” the perfect woman for him, despite how turbulent his romantic life ended up becoming.[4]

Pauline’s marriage to the famous writer was the second-longest, coming in at thirteen years. Over that time, despite the relationship’s eventual demise, Pauline contributed greatly to Ernest’s life and career. Aside from giving birth to two of his three children, she is the greatest editor Ernest had ever worked with, according to him. In addition, her family’s wealth provided for their home and adventures that later fueled so much of Hemingway’s writing.[5]

er, and an overseer of the author’s legacy.[10]

Dog Lovers Unite: See Hem below with his beloved Black Dog. He had many others and I think loved them as much as his cats. A particular favorite was Negrita, a Havana Stray who became a family member. Please consider reading Hemingway’s Cats (by Carlene Fredericka Brennen) which also talks of his dogs. Best to all, Christine

10 Artists and Their Indispensable Canine Companions

Here are 10 artists whose canine companions were indispensable to their craft.

Being alone for long stretches of time can be challenging, and no profession is more famously tied to loneliness than that of the artist. Being holed up in a studio can be lonesome work, and for thousands of years, writers, painters, sculptors, and great thinkers alike have harnessed the sometimes silent, potent power of canine companionship to ease their isolation. Read on to learn more about the canine companions of famous artists.

1. Billie Holliday’s Canine Companions

Billie Holiday with her Dog Mister, 1947, via Library of Congress, Washington

One of the most beautiful aspects of animal ownership is the unconditional love that they can offer to their owners. Dogs are most famous for this trait, being able to stand in for family members and friends of people who have suffered at the hands of fellow humans. Billie Holiday is an artist who found refuge in her canine relationships after having a childhood plagued with abandonment and abuse. Holiday famously had a varied brood of dogs including a beagle, a great dane, a boxer, a poodle, and Chihuahuas.

Mister, the boxer was her favorite and famously accompanied the singer to her shows, waiting patiently in the dressing room during her legendary Carnegie Hall performances. The two of them were separated while Holiday was incarcerated for drug charges, but Mister was there when she was released, jumping on her so enthusiastically and refusing to let anybody else get near her. Onlookers allegedly presumed she was being attacked.

2. Georgia O’Keefe

Georgia O’Keeffe with her two dogs Chia and Bo, via EZ-blitz

3. Pablo Picasso

Picasso with Lump, via Habitually Chic

Pablo Picasso’s dachshund Lump was immortalized in one of Picasso’s most famous line drawings and was infamously the only creature allowed inside the artist’s studio while he was working. He originally belonged to the veteran photojournalist David Douglas Duncan who was merely visiting Picasso. Picasso fell in love with Lump, so the dog never again left his side. The dog has a notoriously dominant personality. He can be seen in Picasso’s many reiterations of Velázquez’s masterpiece Las Meninas. Lump became a silent witness to the many dramatic phases of domestic life that Picasso was so famous for engaging in. Together, they passed through their senior years together, and in 1973 Lump and Picasso died within days of each other.

4. Jackson Pollock

Jackson Pollock with his wife Lee Krasner and their dog Gyp, via Arthive

The famously troubled abstract expressionist has a melancholic legacy and a career that is often overshadowed by his dramatic personal life and traumatic death. Nonetheless, Jackson Pollock and his wife Lee Krasner tried to pacify the artist’s alcoholic temperament in many ways. One such tactic was seen in the adoption of their two dogs Gyp and Ahab. Their role was to accompany Pollock as he toiled in the studio after their move from New York City to East Hampton, Long Island. The house can be visited by fans of the artists and the scratch marks left by Gyp and Ahab are still visible on the back door.

5. Ernest Hemingway

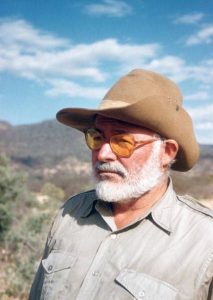

Ernest Hemingway with his dog, via Pinterest

Ernest Hemingway was a cat lover, but during his time in Cuba, he had a dog that he called the Black Dog. The two were often seen around town, moving around the streets and bars of Cuba. Unfortunately, militia men cruelly killed the writer’s Black Dog one night when they broke into Hemingway’s house looking for guns. Black dog is said to have been by Hemingway’s side during the entire writing process of The Old Man and The Sea and For Whom The Bell Tolls.

6. Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo cuddling with her dog, via Skay Oliver

Frida Khalo is one of the most celebrated artists in the world. Her reverence for nature and for the animal kingdom is embedded in her art. While living and working in her native Mexico, Frida famously collected animals of all kinds, from monkeys and eagles to parrots and cats. These animals were mostly rescued and she allowed them to wander freely around her estate. It was well known locally that her favorite of the bunch was called Señor Xolotl, named after the canine deity that protected the underworld. She immortalized him in many of her most famous works like The Love Embrace of the Universe, Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Senor Xolotl (1949).

7. John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck with his Dog Charley, via America Comes AliveThere have been few travel documents that have captured the intimacy between famous artists and their canine companions as extensively as John Steibeck’s travel journal Travels with Charley. A brown standard poodle Charley went on the road with his adoring master to explore the wilds of America. While Steinbeck wrote frantically about the varying types of people they met on their journey, it’s Charley’s hilarious personality that got developed most lovingly throughout the book. Steinbeck portrayed his companion with humanlike characteristics which makes the book so endearing. By the end of the book, the reader is well aware that neither the trip nor the book could have happened without him.

8. Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell in his studio with his dog, via Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge

9. George Stubbs

Horse and Dog Trim by George Stubbs, 1783, via Europeana

One of his paintings Horse and Dog Trim was commissioned after a dog alerted his slave-owning master that one of the slaves was entering their bedroom with a knife. The family of the people who commissioned the painting donated the artwork to Bristol Museum and Art Gallery in acknowledgment of their slave-owning past.

10. René Magritte’s Canine Companion

Rene Magritte with his dog, via Times of IsraelRené Magritte and his wife Georgette were famously obsessed with dogs. Their passion for animals was central to their identity as a couple. This was especially apparent in their relationship with their famous Pomeranians. They traveled nowhere without them. Belgian Airlines even had to make a special exemption for them on a flight in 1965 after Magritte threatened to cancel his MoMA retrospective should they be denied the journey across the Atlantic.

At one point the couple had four dogs, two were called LouLou, and two were called Jackie. Magritte painted his dogs extensively during the 1940s, opting to replace human figures in his work to better convey a sense of the universal horror that emerged in response to the Second World War. He allegedly believed that canine companions seemed to illustrate real life better than humans. They also connected in a more emotionally direct way with the audience.

Read more by Katie Brown

Who can forget Agnes’ “Dear John” letter to Hemingway? And other stinging rejections. Best, Christine

9 Unforgettable Breakup Letters From History

“Going out with you was like going out with a priest.”

1. Agnes von Kurowsky to Ernest Hemingway

The inspiration for the romance in Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was his own affair with Agnes von Kurowsky, a 26-year-old Red Cross nurse he met while recovering from a shrapnel injury in Milan, Italy, during World War I. A few months after Hemingway—who was only 19 at the time—returned to the U.S. to find a place for them to live together, he received a letter in which von Kurowsky not only ended their relationship but also confessed that the time apart had given her the distance she needed to realize that she’d probably never been in love with him.

To add insult to injury, von Kurowsky told him that she’d soon be marrying someone else (an Italian millionaire, though she didn’t mention that). “And I hope & pray that after you have thought things out, you’ll be able to forgive me & start a wonderful career & show what a man you really are,” she wrote.

2. Marlon Brando to Solange Podell

Solange Podell was a French cabaret dancer and actor who met Marlon Brando backstage after a 1947 Broadway performance of A Streetcar Named Desire (in which Brando played Stanley Kowalski, a role he’d reprise for the 1951 film adaptation). The two struck up a relationship, which Brando ended sometime in the late 1940s via a letter written in pencil (and bearing a few spelling errors):

“In order that you won’t think me a complete boor, I am writing you this letter to explain that because of an erratic, flighty, fly-by-night, temperment I wish not to humiliate and degrade your sentiments by seeing you only at my mood’s conveinence. Please accept this letter with an open heart as it is written with fourthright sincerity. I’m sorry I could not have tried harder to be less self indulgent and theirwith, a little more compatable. My intuitions were flawlessly scroupulous but my emotions, unfortunately, unstable. I will remember you with fondness, regard, and appreciation. When we meet in France (perhaps in October) I trust my behavior will be a trifle more adult.”

Brando signed off “with warmth” and a postscript asking that Podell pass along his “kind acknowledgements” to her mother, “if she’ll accept them.”

3. Edith Wharton to W. Morton Fullerton

In April 1910, The Age of Innocence author Edith Wharton penned one hell of a “What are we?” missive to her on-again-off-again beau, journalist W. Morton Fullerton, who was giving her emotional whiplash with his mercurial changes in behavior.

“I don’t know what you want, or what I am! You write to me like a lover, you treat me like a casual acquaintance!” she wrote. “I have borne all these inconsistencies & incoherences as long as I could, because I love you so much, & because I am so sorry for things in your life that are difficult & wearing … Only now a sense of my worth, & a sense also that I can bear no more, makes me write this to you. Write me no more such letters as you sent to me in England.”

Wharton was especially upset because she would have been fine with friendship, but Fullerton’s mixed messages prevented them from settling into any kind of comfortable dynamic. “My life was better before I knew you. That is, for me, the sad conclusion of this sad year. And it is a bitter thing to say to the one being one has ever loved d’amour,” she wrote.

4. Jackie Kennedy to R. Beverley Corbin Jr.

While at Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut during the mid-1940s, a teenaged Jackie Kennedy (then Bouvier) dated a Harvard University student named R. Beverley Corbin Jr. Her letters to him, usually addressed to “Dearest Bev” or “Buddy darling,” shed light on her feelings about boarding school (which she hated) and about Bev himself, whom she came to realize she didn’t actually love.

In one letter from January 20, 1947, she wrote, “I’ve always thought of being in love as being willing to do anything for the other person—starve to buy them bread and not mind living in Siberia with them—and I’ve always thought that every minute away from them would be hell—so looking at it that [way] I guess I’m not in love with you.”

She kept up correspondence with him after that, but the relationship eventually fizzled, and in 1951 she quashed any potential for a rekindling of it when she told him she was engaged to someone else. “What I hope for you is for the same thing to happen as quickly and as surely as it did with me. It will when you least expect it,” she wrote to Corbin. (She called off her own engagement after just a few months and tied the knot with John F. Kennedy in 1953.)

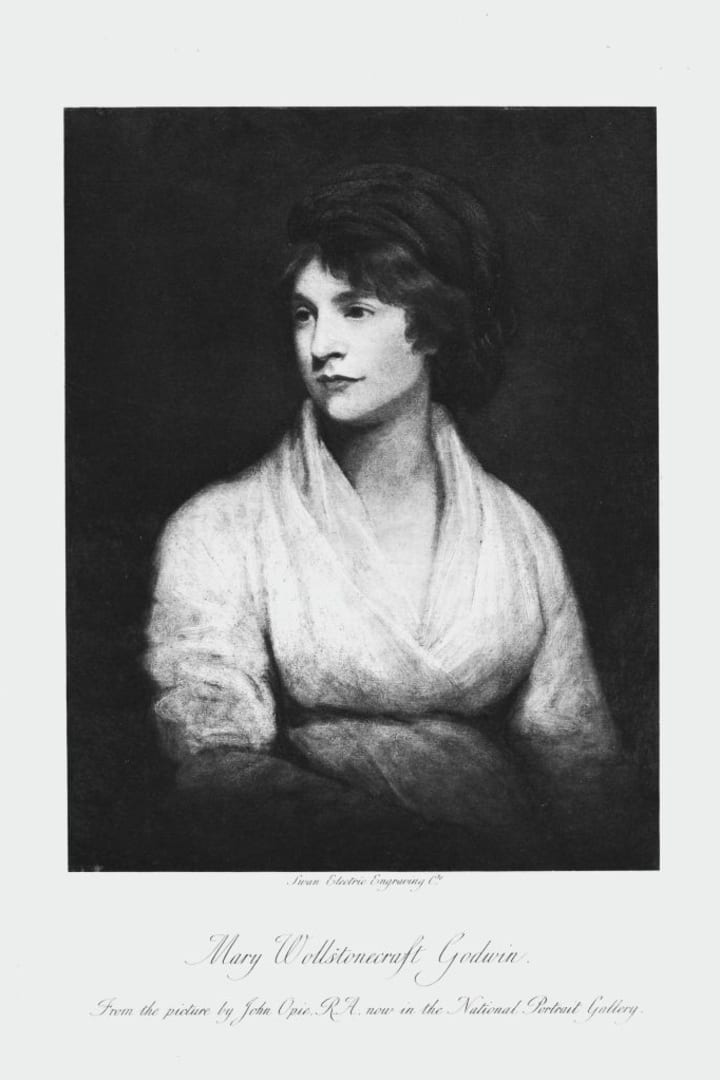

5. Mary Wollstonecraft to Gilbert Imlay

Before Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin and gave birth to future Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, she had a daughter with Gilbert Imlay, an American author and diplomat. They never officially married, and Imlay’s constant traveling, infidelity, and generally poor treatment of Wollstonecraft effectively killed their relationship. In March 1796, Wollstonecraft sent her former lover what could aptly be described as an 18th-century version of a “Delete this number” text.

“You must do as you please with respect to the child.—I could wish that it might be done soon, that my name may be no more mentioned to you. It is now finished.—Convinced that you have neither regard nor friendship, I disdain to utter a reproach, though I have had reason to think, that the ‘forbearance’ talked of, has not been very delicate.—It is however of no consequence.—I am glad you are satisfied with your own conduct,” she wrote. “I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell.”

6. Frida Kahlo to Diego Rivera

In 1953, Frida Kahlo was lying in a hospital bed trying to quickly finish a letter before doctors amputated her gangrene-infected leg. She was writing to her husband, Diego Rivera, who had carried on affairs—including one with Kahlo’s own sister, Cristina—throughout their relationship. (To be fair, Kahlo wasn’t faithful to him either.)

“Let’s not fool ourselves, Diego, I gave you everything that is humanly possible to offer and we both know that. But still, how the hell do you manage to seduce so many women when you’re such an ugly son of a bitch?” she wrote. “I’m writing to let you know I’m releasing you, I’m amputating you. Be happy and never seek me again. I don’t want to hear from you, I don’t want you to hear from me. If there is anything I’d enjoy before I die, it’d be not having to see your f***ing horrible bastard face wandering around my garden.”

She then readily contradicted herself by signing off like this: “Good bye from somebody who is crazy and vehemently in love with you.” The two didn’t cut ties after Kahlo’s operation.

7. Richard Burton to Elizabeth Taylor

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor had been married for nearly a decade when Taylor broke things off, and Burton immortalized his reaction in a letter dated June 25, 1973. “So My Lumps,” it begins, “You’re off, by God! I can barely believe it since I am so unaccustomed to anybody leaving me. But reflectively I wonder why nobody did so before.”

He vacillates between praising her (“Don’t forget that you are probably the greatest actress in the world.”), criticizing himself (“I am a smashing bore and why you’ve stuck by me so long is an indication of your loyalty.”), and painting a portrait of what his life will look like without her.

“I shall miss you with passion and wild regret,” he says. “You may rest assured that I will not have affairs with any other female. I shall gloom a lot and stare morosely into unimaginable distances and act a bit—probably on the stage—to keep me in booze and butter, but chiefly and above all I shall write.”

The Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? stars officially divorced in June 1974, but ended up remarrying in October 1975 (and then got divorced again less than a year later, though they remained close until Burton’s death in 1984).

Writer Anaïs Nin and occasional poet C.L. “Lanny” Baldwin were both married when they began an affair in 1944, but by late summer the following year it had started to self-destruct. Baldwin accused her of being jealous and called her “a kind of dog in the manger with men, [wanting] them all to sit at your feet and be yours, all yours and only yours.”

Nin, who considered Baldwin extremely insecure both as an artist and as a man, practically laughed off his claims, explaining that she only sought affection elsewhere after realizing their own relationship was “dead” and Baldwin could “never enter [her] world”—one of passion, love, and the art that comes from it. “Going out with you was like going out with a priest,” she wrote in a letter postmarked August 25, 1945.

9. Oscar Wilde to Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas

In early 1897, as Oscar Wilde was nearing the end of his two-year prison sentence for “gross indecency” (having relationships with men), he wrote a 55,000-word letter to his lover Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, who hadn’t kept up correspondence with Wilde during his incarceration. Wilde berated Douglas for his insatiable need to control, which Wilde felt he himself had been subsumed by.

“Knowing that by making a scene you could always have your way, it was but natural that you should proceed, almost unconsciously I have no doubt, to every excess of vulgar violence. At the end you did not know to what goal you were hurrying, or with what aim in view. Having made your own of my genius, my willpower, and my fortune, you required, in the blindness of an inexhaustible greed, my entire existence. You took it,” Wilde wrote. “Your pale face used to flush easily with wine or pleasure. If, as you read what is here written, it from time to time becomes scorched, as though by a furnace-blast, with shame, it will be all the better for you.”

The letter is a searing takedown, and without historical context you’d assume it was a death knell for the relationship. But soon after Wilde’s release from prison, he and Douglas were back on. “Everyone is furious with me for going back to you, but they don’t understand us,” Wilde wrote in August 1897. “I feel that it is only with you that I can do anything at all. Do remake my ruined life for me, and then our friendship and love will have a different meaning to the world.”

Moreover, Douglas claimed not to have known about Wilde’s prison letter for years. Upon his release, Wilde turned it over to his friend Robert Ross with instructions to make a copy and send the original to its intended recipient. According to Douglas, Ross never did (though not everyone believes that). What Ross definitely did do was publish excerpts from the letter several years after Wilde’s death under the title De Profundis.

“If I had received the letter, the whole course of subsequent history might have been altered,” Douglas wrote in his 1929 autobiography. “My indignation at Wilde’s grotesque lies and misrepresentations, and his abuse and insults, would perhaps have cured me once for all of my infatuation for him, which still survived so strongly in those days. Again, on the other hand, it is possible, and indeed probable, that I would have forgiven him.”

How it all Began: Hem’s Love Affair with Spain and Bull fighting. I hate bullfighting but admire some of the players and their personalities.

Hemingway and Ronda, a relationship of a hundred years

This year marks the centenary of the American writer’s first visit to Malaga province and the start of his passion for the bullfighting town in the mountains

Alekk M. Saanders

Ronda

Friday, 3 November 2023, 16:01

Not many people know that before his much-written-about visit to Spain in 1923, Ernest Hemingway had already been to Andalucía. In 1919, the writer made a short stopover in Algeciras on his way back to the United States after serving in Italy, where he had gone in response to a plea for ambulance drivers on the Italian front.

However, it was only four years later when Ernest Hemingway came to Spain on the advice of the American novelist Gertrude Stein. In 1923, he left Paris to get the feel of Spain and to spend time in Madrid and Pamplona. The intention of Hemingway was to see the bulls and to try to write about bullfighting based on his own experience.

The young writer and his future publisher, Robert McAlmon, as well as (according to some sources) William Bird, an American publisher, later went south to discover the Andalusian cities of Seville, Granada and Malaga, as well as the town of Ronda.

Apparently, Seville didn’t impress Hemingway. American biographer Carlos Baker said Hemingway found the night in Seville boring. “They watched a few flamenco dances, where broad-beamed women snapped their fingers to the music of guitars… ‘Oh for Christ’s sake,’ he kept saying, ‘more flamingos!’ He could not rest until and McAlmon and Bird agreed to go on to Ronda…”

-kGmC-U21042940305t2H-650x455@Diario%20Sur.jpg)

Ronda was a great surprise to Ernest Hemingway. He immediately fell in love with this spectacular town with an ancient bullring, high in the mountains above Malaga. Moreover, the renowned cradle of bullfighting inspired Hemingway to write. Ronda is mentioned in several of his works. For example, In Death in the Afternoon (1932) Hemingway wrote: “There is one town that would be better than Aranjuez to see your first bullfight in if you are only going to see one and that is Ronda. That is where you should go if you ever go to Spain on a honeymoon or if you ever bolt with anyone. The entire town and as far as you can see in any direction is romantic background… if a honeymoon or an elopement is not a success in Ronda, it would be as well to start for Paris and commence making your own friends.”

Ronda inspired Hemingway to write his novel The Sun Also Rises (translated into Spanish and published in London under the title Fiesta) about a bullfighter. By coincidence, a genuine bullfighter from Ronda became the model for his book.

A matador from Ronda

The same year, when the American writer was in Ronda, 19-year-old bullfighter Cayetano Ordóñez debuted in the Maestranza Bullring. Then, the young man was mainly known by his nickname ‘Niño de la Palma’ because his parents owned the shoe shop in Ronda called La Palma. When Cayetano was 13, the boy performed as a bullfighter in the area’s ranches.

After his debut in Ronda’s bullring, Cayetano Ordóñez was immediately in demand by all the professional and amateur rings in Spain. The American writer followed the talented young bullfighter around the bullrings for a long time, notebook in hand to write down details about and around him. (Incidentally, one story says that once Ordóñez honoured Hemingway’s wife by presenting her with the ear of a bull he killed.)

It is believed that Ernest Hemingway finally met up with Cayetano in a hotel in Pamplona for a long conversation. As a result, the influence of the young matador from Ronda on the book was so great that Hemingway had even to declare that “everything that happened in the ring was true, and everything outside was fiction”. Cayetano Ordóñez was aware of the fiction and never complained about it.

Years later, Ernest Hemingway met Cayetano’s son, Antonio Ordóñez, whom he also followed when he was writing chronicles for Life Magazine. It was in 1959 when Ernest Hemingway arrived in Malaga as a journalist to describe the rivalry of two prominent Spanish matadors – Antonio Ordóñez and Miguel Dominguín (also known internationally for his love affairs with Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth). Their competition in one season of bullfights eventually became the subject of Hemingway’s book The Dangerous Summer. Eventually, Ernest Hemingway became Antonio Ordóñez’s great friend and spent long sojourns at his ‘cortijo’ (a country house) near Ronda.

A FAREWELL TO ARMS: Banned

Library Corner: ‘A Farewell to Arms’ another banned classic

Special for the Grand County Library District

Grand County LIbrary District/Courtesy image

Ernest Hemingway’s novel about World War I, “A Farewell to Arms,” has been named one of the 100 best books of the 20th century. Scholars called it a masterpiece. But…

There’s another side to the story. “A Farewell to Arms” was banned multiple times since it was published in 1929 for sexual content, and for its honest treatment of war. It was banned in Boston, Ireland, Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy.

In the United States, parents sometimes demanded it be removed from school libraries. (Which would prompt students to read “A Farewell to Arms” faster than you can say sexual content.)

I fell in love with this book over 50 years ago when a high school English teacher assigned it. Hemingway presents an exquisite study of young women and men struggling to survive the violence of war. His love story is charged with elements that exceeded my experience at 16, which made it an even more powerful read the second and third time around. (If there are prostitutes in the book, and there are indeed, that’s because prostitutes work their trade in every war. It is a sad historical fact.)

The narrator, Lieutenant Frederick Henry, is a Red Cross ambulance driver for the Italian army’s campaign against Austria and Germany. After he’s seriously wounded, Frederick falls in love with Catherine Barkley, an English nurse working in an Italian hospital.

The plot builds tension in two directions. First, Frederick returns to the front after surgery and his ambulance crew transports increasing numbers of casualties, badly wounded soldiers. Second, Catherine becomes pregnant with his child, and her health soon deteriorates.

Hemingway sends his characters into the depths of melancholy where the reader ponders the story’s great irony. Both love and war carry risks that may be fatal. Over time, Frederick changes from a naive do-gooder to a stone-cold killer. He ends up shooting an Italian soldier for abandoning his comrades. War brings out the very best and the absolute worst in people.

The narrator explains, “I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious and sacrifice and the expression in vain… and I had seen nothing sacred and the things that were glorious had no glory…”

Admittedly, this book isn’t for everyone. Its depiction of World War I combat rings as true today as scenes from Afghanistan. But it shouldn’t have ever been banned. Just as some people prefer a cup of tea to coffee, they don’t have the right to shut down Starbucks. No one individual or mob should have the right to ban a book that millions of readers might learn from.

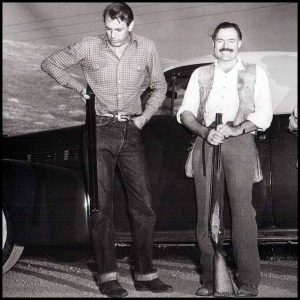

Great article about the friendship of Hem and Coop: So different and yet . . .

-

-

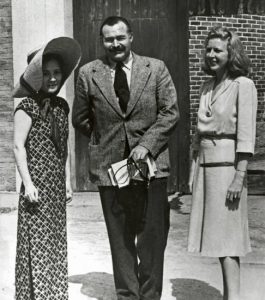

Celebrity friendships are nothing new, with the business of entertainment bringing together many gregarious comedians, actors and more with bulging egos, but some are more eyebrow-raising than others. Martha Stewart and Snoop Dogg are certainly a curious friendship, as is Elton John and Eminem, but for my money, no duo are more mysterious and alluring than actor Gary Cooper and author

-

-

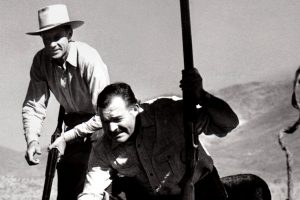

Star of such classic movies as 1936’s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town by director Frank Capra and 1952’s High Noon by Fred Zinnemann, Cooper was one of the great stars of mid-20th-century cinema. Earning two Academy Awards across the course of his career, for 1942’s Sergeant York and High Noon, Cooper was a prominent name in the industry, recognised as one of the very best of his time. Hem with the “Long-legged son of a bitch.” Hem with the “Long-legged son of a bitch.”

Hem with the “Long-legged son of a bitch.”

Despite their totally separate lives in contemporary culture, Cooper and Hemingway became good friends from 1940 until 1961, with their relationship sparking following the film adaptation of Hemingway’s debut novel A Farewell to Arms. The film, named after the novel and directed by Frank Borzage, received widespread critical acclaim, but Hemingway wasn’t best pleased with the movie, apart from the performance of one Gary Cooper.

Many years later, the author promoted Cooper for the role of Robert Jordan in the upcoming adaptation of For Whom the Bell Tolls, even going so far as to state that the literary character was based on Cooper’s own integrity. The actor earned the role and became the greatest asset of the otherwise underwhelming film, strengthening the friendship of the two stars.

Sharing a love for the great outdoors, the unlikely duo spent many days across several years shooting duck and pheasant in the summer before taking to Sun Valley in the winter to ski. The pair were excitable, fuelled by a youthful exuberance that led them to seize life by the horns, poetically gazing over the wilderness with a similar sense of wonder to their favourite author, Rudyard Kipling.

As Cooper said of friendship and his true passion for the outdoors in the book Gary Cooper off Camera: A Daughter Remembers: “The really satisfying things I do are offered me, free, for nothing. Ever go out in the fall and do a little hunting? See the frost on the grass and the leaves turning? Spend a day in the hills alone, or with good companions? Watch a sunset and a moonrise?… Free to everybody”.

Indeed, Hemingway’s view was reciprocated, admiring Cooper for his passion for the outdoors and his surprising similarity to his charismatic, powerful on-screen persona. Stating in the book Gary Cooper: American Hero, Hemingway lovingly exclaimed: “If you made up a character like Coop, nobody would believe it. He’s just too good to be true”.

Rather poetically, the pair died within just seven weeks of each other in 1961, but not before they enjoyed one last holiday together, taking to Sun Valley in January of that year for a final hike through the snow.

The relationship between the pair is explored in the 2013 documentary Cooper and Hemingway: The True Gen by filmmaker John Mulholland, who had plenty to say about the unpublicised relationship.

During an interview about the movie and the pair’s relationship, Mulholland stated: “Hemingway and Cooper both grew up under the sway of Teddy Roosevelt — live a dangerous life, test yourself, be a man of action. In many ways, Hemingway and Cooper defined masculinity for the first half of the 20th century. Stoic, strong, keep silent about your problems. Your emotions. They managed to hide, both men, their inner selves — sensitive, well-read, intelligent, etc”.

Take a look at the trailer for For Whom the Bell Tolls, the role which sparked the friendship between Cooper and Hemingway below.

Hemingway and the Plane Crashes

Hemingway Survived Two Plane Crashes. A Letter About Them Just Sold for Over $237,000.

“I am weak from so much internal bleeding,” the novelist wrote to his lawyer. “Have been a good boy and tried to rest.”

A four-page letter that Ernest Hemingway wrote to his lawyer after the writer survived two back-to-back plane crashes in East Africa in 1954 sold at auction for $237,055, according to Nate Sanders Auctions.

Bidding for the letter started at $19,250 and there were 12 total bids before the letter was sold last week, according to the auction house, which is based in Los Angeles and specializes in autographed items. It’s unclear who bought the letter.

Hemingway, 55 at the time, had been visiting Congo, Kenya and Rwanda with his fourth wife, the American journalist Mary Welsh Hemingway, on a hunting safari. Over the course of a few days, the couple were involved in two crashes, the second more violent than the first, that would leave their mark on him for the rest of his life.

In the first crash, their plane “clipped a telegraph wire and plunged onto the crocodile-infested shores of the Nile,” according to PBS. Hemingway wrote about his trip to Africa in Look Magazine in 1954, which included a 16-page spread about his safari to Kenya.

The couple had been reported missing when their plane failed to land as expected for refueling, The A.P. reported. They were later brought to a plane meant to rescue them, which then itself “crashed and burned on the take-off,” the news agency said. Everyone aboard escaped.

Dr. Andrew Farah, who wrote a book about Hemingway’s brain, described the second crash as more fiery and more violent, during a 2017 talk at the John F. Kennedy library. The pilot kicked out his front window to escape and save his passengers.

“He pulls Mary out, but Hemingway’s too big to get out the window,” Dr. Farah said. To escape from the aircraft, Hemingway, his shoulder still injured from the earlier crash, “chooses very unwisely to bust open the door with his head, giving himself a skull fracture and another concussion,” Dr. Farah said.

That decision would affect Hemingway’s brain for the rest of his life. After the crash, Dr. Farah said, “his memory was worse” and he had persistent headaches.

Hemingway memorabilia such as letters with his original signature or first editions of his books are auctioned off regularly and often fetch thousands of dollars, with some going for much higher. In Philadelphia in February, a first edition of Hemingway’s “In Our Time” from 1924 was auctioned for $277,000. Another signed letter was auctioned off last month at Nate Sanders Auctions, but went for much less: $6,875 after only one bid. In February, a more modern copy of “The Old Man and the Sea” went for more than $10,000 for a special reason: It had been the copy taken out of a high school library by a young Kobe Bryant.

In the crash letter — which was written on April 17, 1954, but was misdated as 1953 — Hemingway recounted the crashes and their effect on him, and told his lawyer Alfred Rice that he needed money. He also expressed his dissatisfaction with Abercrombie & Fitch, the brand now known for its all-American apparel, which at the time was more known for selling outdoor gear like guns.

“They sent me two .22 rifles of a type I did not order, several hundred rounds of ammo of another type than I had ordered,” Hemingway wrote, adding that he had to “shoot my first lion with a borrowed .256 Mannlicher which was so old it would come apart in my hands and had to be held together with tape and Scotch tape. Their carelessness in shipping imperiled both my life and livelihood.”

Much of the letter, which was handwritten on stationery from the Gritti Palace-Hotel in Venice, also goes into the gritty details of his injuries.

“I am weak from so much internal bleeding,” he added. “Have been a good boy and tried to rest.”

Hemingway’s wife did not come out of the plane crashes unscathed. According to an article by the United Press, she had two cracked ribs and was limping. Hemingway also focused on her mental state: “Mary had a big shock and her memory not too hot yet and it will take quite a time to sort things out,” he wrote to Mr. Rice.

Still, a sense of normalcy is infused in the letter. As Hemingway wrote on the final page: “Everything is fine here.”