|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

Author: Christine Whitehead

OK KIDS, you can do this at home but don’t drive! Best, Christine (Some photos added by me.)

For Whom The Bell Tolls Banned in FLA.: There are no words.

Banned Books are Fighting Back

Book Publishers, Authors, and Parents Are Fighting Back Against Florida Book Bans

It is Banned Books Week and MidPoint addressed it on September 25, 2024. Recently, Florida and Texas are the states in competition for the most books banned in public schools, according to PEN America. Missouri, Utah, and South Carolina are not far behind in the competition for which state is the most retrograde, revisionist, and racist, at least in the book-banning event of the UNWOKE Olympics. But now, the books are fighting back. In a landmark federal lawsuit filed last month against the Florida Board of Education by a group of the major U.S. book publishers, The Authors’ Guild, public school parents, and students, a challenge has been mounted to the Florida law that bans books containing sexual content deemed “pornographic.”

Classic Books Have Been Banned in Florida

As a result of Florida law HB 1069, hundreds of titles have been banned across the state since the bill went into effect in July 2023. The list of banned books includes classics such as Brave New World by Aldous Huxley, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain, as well as contemporary novels by bestselling authors such as Margaret Atwood, Judy Blume, and Stephen King. Among nonfiction titles, accounts of the Holocaust such as The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank have also been removed.

The First Amendment Protects the Right to Receive Ideas in Books

Our guests today to discuss this lawsuit were Dan Novack, V.P and General Counsel of Penguin Random House publishers, the lead plaintiff in the case, and Judi Hayes, an Orange County Public Schools parent suing on behalf of her sons who attend public school there. Dan Novack explained that the law was being challenged on First Amendment Free Speech grounds, primarily because it provides for the censorship and removal of any book that is alleged to be “pornographic,” even though “pornographic” is not a term with a real legal definition. According to Penguin Random House, unless a book is found to be “obscene” under the U.S. Supreme Court’s legal definition, it is lawful, but, ultimately, whether it should be available to students in schools is a determination best left to trained educators, librarians, and a child’s parents, and not to random individuals of varying sensibilities. Florida’s law instead censors and removes the targeted book first, upon someone’s objection, then keeps the book out of school libraries, all while the book goes through a vague and lengthy review process, which may vary by county and result in inconsistent determinations around the state applying to the same book. Both Dan Novack and Judi Hayes argued that the decision of whether or not a child is ready and mature enough to read certain books should be made by their parents and educators, and not by an outside individual seeking to remove access to books from all children, which is the process the law currently provides. While the State may argue that it has the right to restrict speech in schools to further “pedagogical interests,” the broad right to receive ideas is fundamental to the First Amendment; that right should be protected to the greatest extent against State restrictions.

You can listen to the complete show here, on the WMNF app, or as a WMNF Midpoint podcast from your favorite podcast purveyor.

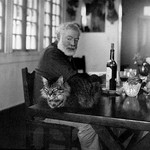

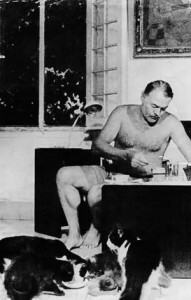

A Man and his Cats (Photos of Hem’s cats added by me.)

The Blue Collar Bookseller review: The Hemingway Hoax

The Blue Collar Bookseller review: The Hemingway Hoax

-

- Kevin Coolidge

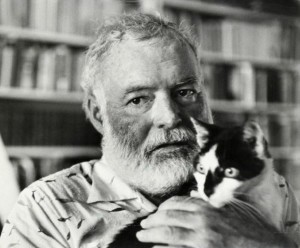

- Never trust a man who doesn’t like cats…Irish proverb

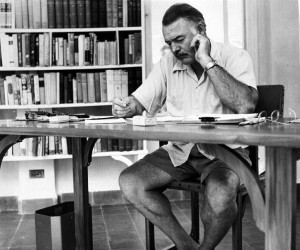

Uncanny focus, curious, observant, a dislike for being disturbed — they sit for long periods of time and sleep more than they probably should. Writers are a lot like cats. Complex, unorthodox, full of personality quirks, hunting when he wills it, working when it’s time — a writer is not a herd animal.

Now, I’m not saying you have to have a cat to be a writer, but the best writers have at least one cat. Mark Twain, Neil Gaiman, Ray Bradbury, Robert Heinlein — they all loved cats. It helps to have someone to understand that writing is a process. You aren’t being unproductive or lazy. You are cultivating stillness.

One of the most influential and manliest writers* of the 20th Century, Ernest Hemingway, was a dedicated feline lover. Like most cat hoarders, he started with a single cat. A ship’s captain gave Hemingway a white six-toed cat, named Snowball.

Today, the Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum on Key West is a playground to approximately 40-50 polydactyl cats. Cats normally have five front toes and four back toes. Not all the cats at the Home have the extra thumb, but they all carry the gene, and can give birth to a Hemingway cat.

If you take the tour, you’ll hear that these kitties can trace their lineage back to the original Snowball, but James Nagel, a Hemingway scholar, claims that Hemingway didn’t have cats when he lived in that house.

“Hemingway liked cats but Pauline, to whom he was married, wanted peacocks. So they got peacocks for the yard … The time when he had so many cats was when he lived in San Francisco de Paula, Cuba.” The estate in Key West is just one of the many places trying to cash in on the writer and the cats associated with him, claims Nagel.

Regardless of where you fall on the Key West cat debate, Hemingway wrote some of his best work in this home, including the final draft to A Farewell to Arms and the short story classic The Snows of Kilimanjaro. I rather suspect there was at least one cat around.

Waiting, seeking, stalking — striking and feasting on the flesh of your thoughts to satisfy a primal need. You are a writer, and you must feed the hunger, and the cat. OK, you can get yourself a big slobbery dog**, but if you want to be a writer that is remembered, you need to get yourself a cat…

*Hemingway ran with bulls, hunted, fished, went on safari, occasionally took a rifle with him, though he preferred his fists. He wrestled bears, rode sharks, and never shed a tear when he got a paper cut. This is also a man that named a cat Snowball…

**Don’t buy into all the cat crap. Jim Kjelgaard, Wilson Rawls, Jack London — all were dog lovers. Of course, if you have a dog, the stipulation is that you are an outdoor writer.

Kevin Coolidge is currently a full-time factory worker, and a part-time bookseller at From My Shelf Books & Gifts in Wellsboro, Pa. When he’s not working, he’s writing. He’s also a children’s author and the creator of The Totally Ninja Raccoons, a children’s series for reluctant readers. Visit his author website at kevincoolidge.org

Across the River and Into the Woods–THE MOVIE (some photos added by me)

Hemingway’s Worst Novel Is Now a Slightly Better Movie

In Across the River and Into the Trees, Liev Schreiber, a very fine actor whom I’d never thought of as resembling Ernest Hemingway, has been made up to evoke, if not exactly mirror, the legendary American author. With his wide face, white beard, sad eyes, and a chest somehow both barrel-shaped and concave, the actor brings a hint of the wounded, rueful poet to the part of the weary Colonel Richard Cantwell, an American veteran of both World Wars now wandering aimlessly through postwar Venice. Cantwell is a tough old soldier, but he seems more like a guy who’d rather talk about art and literature than war and conquest — or, for that matter, duck hunting, an activity he tells everyone he’s hoping to do a lot of during his Venice sojourn, but which he seems not particularly enthusiastic about.

The creation of this spiritual and visual bond between author and protagonist in the film makes sense. Cantwell was based on a couple of people, but he was also the most autobiographical of Hemingway’s characters, in ways both touching and prophetically ominous: About a decade after the novel’s 1950 publication, Hemingway would commit suicide in the same way Cantwell does at the end of the book, thus giving the character’s enveloping sadness a heartbreaking historical resonance. (Hemingway’s own father had done something similar, and the idea haunts much of his work.)

One doesn’t need to know all this to understand or appreciate Paula Ortiz’s film of Across the River and Into the Trees, which takes Hemingway’s ambling, memory-inflected tale and fashions it into a melancholy love story, focusing largely on Cantwell’s romantic conversations and wanderings through Venice with a young, questioning countess, Renata, played by Matilda De Angelis. But in so doing, Ortiz (and screenwriter Peter Flannery) remove what made the novel, for all its massive flaws, unique. The book is built around Cantwell’s memories, as expressed through his own fleeting flashbacks and his interactions with Renata. In these moments he speaks not just of his own life but of any number of things: authors, art, alcohol, battles, generals, the relative quality of French soldiers, the need to forgive your enemies. And it’s all rendered in language of almost unbearable simplicity — even for Hemingway — perhaps in an effort to evoke the cultural differences between the weary American and the young Italian.

There’s no real way to adapt all that without getting laughed off the screen, so Ortiz and Flannery opt for more naturalistic dialogue. But they also keep the memory-play to a minimum, opting instead for a couple of brief, key flashbacks to a bloody wartime encounter in the forest between Cantwell’s soldiers and the enemy. It all makes perfect sense, craft-wise, but it also results in something pedestrian. The movie plays at times like one of Richard Linklater’s Before films, but without the improvisational verve that gave those works such urgency and heart.

Ortiz’s film does have its charms. The Venice locations are presented with all their nocturnal mystery intact, their shadows and deep colors allowing us to imagine beyond the frame. De Angelis is radiant — veteran Spanish cinematographer Javier Aguirresarobe contrasts the smooth, luminous beauty of her features with the grizzled, combat-zone roughness of Schreiber’s — and the actress has captured the ethereal nature of Renata, who serves in the novel as a figure of both emotional reconciliation and death. The filmmakers even give her something to do besides just be a vessel for Cantwell’s reveries: He first meets her when she gives him a ride in her gondola. Schreiber is of course always interesting to watch. He’s one of those actors who has become more compelling with age, even as the big parts seem to be drying up. It’s nice to see him take center stage in a movie again.

This is tough, tough material. The novel of Across the River and Into the Trees got vicious reviews at the time, and although its reputation has been somewhat redeemed over the ensuing decades (partly because several of Hemingway’s many posthumously edited and released works are so, so much worse), it’s never really found an audience comparable to the writer’s beloved classics. It doesn’t have much of a story, and a lot of it reads like self-parody. Hemingway’s characteristic minimalism feels less like poetic concision this time around and more like an inability to find the right words; the meter and personality are there, but gone are the depth and dimension, the seemingly effortless shading that made Hemingway’s other characters pop off the page. The result is that while Cantwell might be the most haunted of the author’s literary avatars, he’s also the most one-dimensional.

So, it’s a problematic work but an intensely readable one; I think it’s the worst thing Hemingway published in his lifetime and yet I’ve somehow managed to read it four times. As S.F. Sanderson, one of the book’s defenders, said at the time: “[It] reads, in many passages, as if Hemingway-the-legend were being interviewed by the press.” Is there any way to translate that to the screen? Is it even worth trying? Across the River and Into the Trees gives it a shot, and it doesn’t succeed, but there’s a nobility in such failure, too. A certain long-deceased Nobel laureate might have had something to say about that.

MORE MOVIE REVIEWS

Newest Press Review of Hemingway’s Daughter

Thank you to everyone who has been so supportive of the novel’s journey for a book that is so close to my soul. Heartfelt gratitude. Christine

Christine Whitehead Releases a New Fictional Novel: “Hemingway’s Daughter”

Stories often echo the realities of life in the world of literature. Christine M. Whitehead [https://christinewhitehead.com/] is a seasoned author and practicing divorce lawyer from New England, who has recently invited us to glimpse into her emotionally resonant novel, “Hemingway’s Daughter [https://christinewhitehead.com/about-the-books/].” This novel takes you on a journey that makes you witness the aspirations and struggles of a character who seeks to redefine her destiny against the background of a legendary literary legacy.

This fictional story is set in a time when gender roles were being defined rigidly. “Hemingway’s Daughter” tells us the story of Finn Hemingway, a character who is born out of time and expectations. She is a woman with dreams that are too large for the confines of her reality – a reality where Ruth Bader Ginsburg is being marginalized and a woman’s achievements in law are overshadowed by her male counterparts. Here, Finn embodies the spirit of every woman who dared to dream big in a world that tried to keep her small.

Finn has aspirations that are threefold: to become a trailblazing trial lawyer, to find true love despite a family curse that has doomed the Hemingways to tragic endings in romance, and most importantly, to leave an unforgettable mark on her father’s writing. Ernest Hemingway is a towering figure in literature who yearned for a daughter, and Finn Hemingway is the living manifestation of that longing. Her journey is not just about reaching her goals but also about experiencing the complexities of familial expectations and the burden of a famous surname.

Having a vast background as a divorce lawyer and living on a rural farm in Connecticut, Christine Whitehead fills this story with raw authenticity and heartfelt emotion. Her love for animals and nature adds a special charm to her storytelling, which is reflected in her idyllic farm life surrounded by dogs, horses, and a brave cat. The novel does not just have a compelling plot but also explores themes like gender inequality, the pursuit of love, and the quest for personal identity.

In “Hemingway’s Daughter [https://www.amazon.com/dp/1916965636/?utm_source=google&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=Hemingways+Daughter],” readers will find a story that connects with the struggles of every individual who has ever dared to dream in the face of adversity. It is a story that defines the enduring spirit of determination and the belief that the word ‘almost’ can be a light of hope in the pursuit of one’s dreams.

“Hemingway’s Daughter” goes beyond being just a mere novel. It inspires and mirrors the obstacles that women have faced throughout history. It pays homage to the everlasting impact of one of the most influential writers of all time. This fictional book is not just for fans of Hemingway but for anyone who believes in the potential of dreams and the strength it takes to chase them.

Media Contact

Company Name: Audiobook Publishing Services;

Contact Person: Christine Whitehead

Email:Send Email [https://www.abnewswire.com/email_contact_us.php?pr=christine-whitehead-releases-a-new-fictional-novel-hemingways-daughter]

Country: United States

Website: http://www.christinewhitehead.com

Two Amazing new Hemingway Themed Books!

Something to look forward to! Hemingway movie of his last novel.

Cannes: Liev Schreiber, Josh Hutcherson-Led Ernest Hemingway Adaptation Lands at Bleecker Street

Bleecker Street has nabbed the North American rights to “Across the River and Into the Trees,” an upcoming movie starring Liev Schreiber (“Ray Donovan”) and Josh Hutcherson (“The Hunger Games”). The film is directed by Paula Ortiz, who is best known for her work on “The Bride,” and is expected to debut in the fall of 2023 for a theatrical release.

An adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s last full-length novel that he published in his lifetime, the movie is set in post-World War II Italy. After American Army Colonel Richard Cantwell (Schreiber) survived the war and emerged as a war hero, he has to grapple with a new battle: his own illness. Determined to find some peace, he enlists a military driver to bring him to his old haunts in Venice. But as his plans unravel, a budding relationships with a young woman teaches him to hope again.

In addition to Schreiber and Hutcherson, “Across the River and Into the Trees” stars Matilda De Angelis (“The Undoing”) and Danny Huston (“The Aviator,” “Succession”). The screenplay adaptation comes from BAFTA Award Winner Peter Flannery (“The Devil’s Mistress”).

Also Read:

‘Beau Is Afraid’ Lights Up Specialty Box Office With 2023’s Best Per-Theater Average

The upcoming film is executive produced by William J. Immerman, Laura Paletta, David Beckingham, Justin Raikes, Simon Fawcett, Jonathan Taylor, Hani Musleh, Harel Goldstein and Rick Roman. Additionally, Robert MacLean and Michael Paletta for Tribune Pictures, alongside John Smallcombe, Kirstin Roegner, Ken Gord as well as Spring Era Films’ Jianmin LV and Daxing Zhang will produce. Andrea Biscaro serves as the Italian line producer.

This film will continue Bleecker Street’s push to support female filmmakers. Its 2023 slate alone consists of 80% female-directed films, including Frances O’Connor’s “Emily,” Catherine Hardwicke’s “Mafia Mamma,” Laurel Parmet’s “The Starling Girl,” Alice Troughton’s “The Lesson” and Meg Ryan’s first feature film in eight years, “What Happens Later.”

HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MR. HEMINGWAY–July 21 1899

Hemingway: Funny? We’ll See!

WHAT’S SO FUNNY ABOUT ERNEST HEMINGWAY? NEW COMEDY SHOW TAKES ON A LEGEND

What’s so funny about Ernest Hemingway?

James Scott Patterson, a writer and stand-up comedian currently in Key West, found plenty of material beneath the novelist’s larger-than-life mystique.

“This guy’s life was dark,” said Patterson. “I’m trying to hit this note where the tone is sort of reverential. But every joke is about what a jackass he was. The jokes are about the myths, his own myth-making. It’s tricky. I’m presenting the overall arc that he was this estimable figure. He was taken seriously.”

“Hemingway in a Funny Way” will debut at Comedy Key West at 5:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 20, and is scheduled every Wednesday through April 17.

The one-hour show is billed as a special happy hour. Tickets are $20 and include a glass of wine. Doors open at 5 p.m. and the shows start at 5:30.

[Disclaimer: Gwen Filosa has been doing stand-up at Comedy Key West since 2017. ]

For the show, Patterson will present a video of Hemingway images and other photos while standing to the side of the stage narrating it all. Then he’ll take questions from the audience.

I know a ton about Hemingway, but I’m not an expert,” said Patterson, 48, a New Jersey-born comic who became a regular performer at Comedy Key West in 2021. “It’s a little daunting to do it. I’m more curious than anyone how this will go.”

For “Hemingway in a Funny Way,” Patterson steered away from the most commonly told Hemingway tales.

“I found stuff about his childhood, his high school paper, The Trapeze in Oak Park, Illinois,” Patterson said. “Then I have stuff about the wars. I’m hoping all of these are stories no one has heard before. It’s weird stuff.”

Patterson based everything on his research into the life of Hemingway – who was known for embellishing and exaggerating his life experiences.

“I have citations for everything,” Patterson said.

‘Clever and dark’

Known for his dark humor, Patterson has performed regularly at Comedy Key West since 2021.

“The perfect blend of clever and dark,” said Steven Crane, another regular comedian at the club. “James’s jokes can heal old wounds with abundant laughter.”

Patterson has appeared on Comedy Central, at the prestigious Just for Laughs Montréal comedy festival and has his own special, Superior Design, available on streaming sites.

At 21, Patterson moved to Boston for its comedy club scene and scored success. He started appearing on Comedy Central after coming in third in their national comedy contest. He’s bounced around cities for years, racking up about 10 years total in Los Angeles, with stints in New York and Denver.

Choosing Hemingway

Patterson wanted to create a new type of comedy show for the local comedy club, Comedy Key West, and Hemingway was an obvious choice.

The Hemingway tourism route runs directly through Patterson’s stomping grounds in Key West: the Hemingway Home and Museum sits at 907 Whitehead St. while the comedy club is at 218 Whitehead.

“The club is between his house and Sloppy Joe’s,” Patterson said.

So, two months ago, he assigned himself a crash course in literature and history.

“By the time the show has started, I will have reread all the novels,” Patterson told Keys Weekly. “I had read most of his books, but when I was 20.”

On top of the nine Hemingway novels, Patterson read five biographies of the writer, who in the 1930s lived in a mansion in Key West and made headlines for his fishing expeditions, sparring sessions and drinking bouts.

“Hemingway was one of the most famous people,” Patterson said. “You could claim there’s still never been a more recognizable novelist. His face was recognizable to everybody.”

Patterson admits he signed on for a larger workload than he expected, but his

years of stand-up, comedy writing intersect in “Hemingway in a Funny Way.”

Stand-up comedy has a DIY work ethic and an addictive payoff that requires big risks, not unlike fiction writing.

“Ninety percent of the stuff you come up with doesn’t work,” Patterson said. “I’m more surprised when they work than when they don’t. Stand-up has a very weird property where you feel bizarrely in control of the room. That’s not even a part of my personality. It’s a bizarre feeling to be the only one in the room talking.”