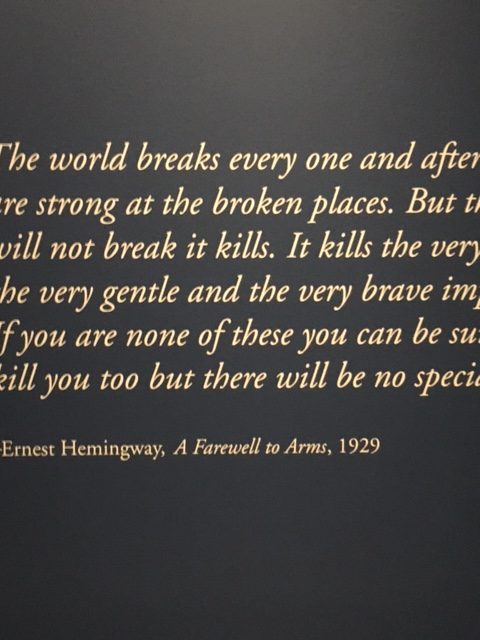

The largest collection of Hemingway letters and memorabilia is in Boston, Massachusetts at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. Mary Welch Hemingway, Hem’s fourth wife, made that selection. While Hemingway and John Kennedy never met, Kennedy respected Hemingway’s writing and person. In his own Pulitzer Prize winning book, Profiles in Courage, Kennedy cited Hemingway’s description of courage, writing that, “This is a book about the most admirable of human virtues — courage. ‘Grace under pressure,’ Ernest Hemingway defined it.”

Hemingway was invited to President Kennedy’s inaugural address but he had to decline due to ill health. The inauguration was in January 1961 and Hem died in July 1961. While there was a ban on travel to Cuba in 1961 due to the tension from the Bay of Pigs incident, Mary was permitted to return to the Finca, their home in Cuba, to retrieve papers and personal possessions after Hemingway’s death. The Kennedy Administration worked to make this possible. Fidel Castro personally promised safe passage for Mary so that she could collect and ship artwork, notes, letters, and beloved possessions.

There were many suitors for these prized items. Mary maintained her connection with the White House and was the guest of President and Mrs. Kennedy at the White House dinner for the Nobel Prize winners in April, 1962. Hem was honored as one of America’s distinguished Nobel laureates and Frederic March read excerpts from the works of three previous Nobel Prize winners, Sinclair Lewis, George C. Marshall, and Hemingway – the opening pages from his then-unpublished Islands in the Stream.

In 1964, Mary contacted Jacqueline Kennedy and offered her husband’s collection to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, which was still in the planning stage with the intent that it be a national memorial to John F. Kennedy. The collection included drafts of various novels of Hemingway, rewrites, and a sense of how he wrote and revised.

In 1972, Mrs. Hemingway deeded the collection to the Kennedy Presidential Library and began depositing papers in its Archives.

On July 18, 1980, Patrick Hemingway, Hem’s older son with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis dedicated the Hemingway Room in the JFK Library.

I’m going to visit it again in a few weeks. If any of you have been, I’d love to hear your impressions. I always get a thrill seeing a photo that I haven’t seen before. It makes it all come alive for me anew. The building itself is modern, a short cab ride away from Fanneuil Hall in downtown Boston, on the water and still being developed. For those of us who love and follow Hemingway, it is worth the detour. There was the original notes that Scott Fitzgerald gave Hemingway for The Sun Also Rises. That will give you shivers.