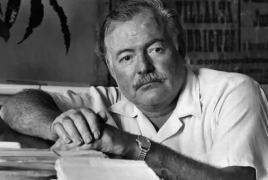

Did Hemingway have a favorite wife? Of course he did despite each wife having suited him at the time he married each.

Hemingway had four wives: Hadley Richardson, Pauline Pfeiffer, Martha Gellhorn, and Mary Walsh. Of the four, three were from the St. Louis area. Only Mary was from elsewhere—Minnesota. Hadley was the great love of his life, in my opinion. Surely in retrospect, based on A Moveable Feast, she was.

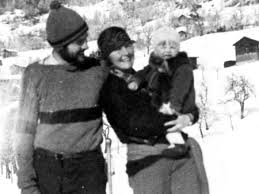

Hadley and Hem were married on September 3, 1921 in Horton Bay, Michigan, and they spent their honeymoon at the family summer cottage, which featured significantly in Hemingway’s early short stories. Hemingway’s biographer, Jeffrey Meyers, noted in his biography that, “with Hadley, Hemingway achieved everything he had hoped for with Agnes: the love of a beautiful woman, a comfortable income, a life inEurope.” (Agnes was Agnes Von Kurowsky, his nurse in Italy who was the prototype for Catherine Barkley, the heroine of A Farewell to Arms). He called her Tatie or Hash.

While the Hemingways had little money as they headed to Paris, Hadley’s modest trust fund sustained them. They had a small apartment, as well as a rented studio for Hemingway’s work, plus an abundance of expatriot and European friends, most of whom were writers. Gertrude Stein’s salon was nearby and she was a mentor, although ultimately there was a falling out.

One of the great dramas of their marriage occurred in December, 1922, when Hadley was traveling alone to Geneva to meet Hemingway there (he was covering a peace conference), and Hadley lost a suitcase filled with Hemingway’s manuscripts. One can only speculate about what impact this ultimately had on his writing. At the time, he was devastated. As any writer knows, you can never recreate the first cut. However, scholars opine regularly about whether the loss enabled him to start from scratch and do a better job or whether it was an irreplaceable loss. Clearly, he did okay despite . . .

Still, Hadley was there at the beginning before he was the famous Ernest Hemingway. She was there during the ever-productive Paris years, which proved to be a touchstone gift that kept on giving. She funded his ability to write in Paris, enabling him to eventually at warp speed finish the first draft of The Sun Also Rises in six weeks.

To Hadley’s dismay and hurt, she never figured significantly as a character in any of Hemingway’s books, which did tend to be based on actual people in his life. The fictional memoir, The Paris Wife, paints Hadley as wounded that she was written out of The Sun Also Rises while starring Lady Brett Ashley, who’s based whole hog on Lady Duff Twysden.

Hadley settled into married life as a wife and mother, but trouble was not far away. She and Hem met the charming Pfeiffer sisters. Although initially Hemingway thought Jinny was the more attractive, it was the petite Pauline, a writer for Paris Vogue, who ultimately captured his attention. As Pauline played the role of loyal, jokey pal to both Ernest and Hadley, she set her cap for Hem and he fell hard.

Now it was Hadley’s turn to be devastated. Initially, she resisted a divorce but later agreed. Their son, John aka Jack aka Bumby, was about 4 years old at the time. Hadley graciously accepted Hemingway’s offers of the royalties fromThe Sun Also Rises as child support and alimony. At the time, she had no way of knowing whether those would amount to anything. As of that date, Hemingway’s writings had not created much money at all so for all Hadley knew, this new style of novel might do little in the way of sales.

Of course, the rest was history. Hadley and Hemingway divorced in January of 1927. The Sun Also Rises was published shortly before the final formal divorce. Hemingway married Pauline Pfeiffer in May of 1927. When The Sun Also Rises was made into a film, profits from the film also went to Hadley.

Hadley and Hemingway remained friendly throughout their lives.She and Hem didn’t socialize, but they were in touch regarding their son, Jack, who was known in the family as Bumby).

Hadley stayed on in France until 1934. Paul Mowrer was a foreign journalist for the Chicago Daily News. She’d known him since the spring of 1927. Mowrer was no light weight himself, having received the Pulitzer Prize as a foreign correspondent in 1929. Hadley and Paul married in London in 1933. The Mowrers ultimately moved to a suburb of Chicago.

After the divorce from Hemingway, Hadley saw Ernest only once again although they wrote to each other regularly. She and Paul Mowrer ran into him while vacationing inWyoming in Sept 1939. Hadley died on January 22, 1979 in Lakeland,Florida. She is the grandmother of Mariel and Margaux Hemingway, who are the children of Jack/Bumby.

Did Hem have a favorite wife? Hell, yes. Her name was Hadley.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/mar/10/hadley-freeman-richardson-ernest-hemingway

August 3, 2020 – 18:10 AMTPanARMENIAN.Net – Legendary writer Ernest Hemingway’s published writings are riddled with hundreds of errors and little has been done to correct them,

August 3, 2020 – 18:10 AMTPanARMENIAN.Net – Legendary writer Ernest Hemingway’s published writings are riddled with hundreds of errors and little has been done to correct them,