I don’t commemorate Hemingway’s Death for obvious reasons. I have a party on his birthday later this month. However, I will reprint an article below that I enjoyed written at the time of his death by Sidney Feingold for the Daily News. It was published the day after his death on July 3, 1961. It’s long but please read what you wish.

Ernest Miller Hemingway gloried in toughness. He shrugged off brushes with death as being part of life. He counted his many wounds proudly. He lived it up boisterously and sneered at those who did not.

And he wrote about it all, earning a bankful of the world’s prizes for literature.

That he died by the gun was fitting. A man who had dared death to seek him out in three wars and on countless safaris in the wilds of Africa was not meant to die in bed or of old age.

Nobel Winner in ’54

Hemingway knew hospitals as baseball players know rival stadiums. He looked at them with the same competitive eye of winning.

Many considered him the greatest living American novelist and short-story writer. Hemingway – who did not exactly dispute their judgement – did indeed have the Pulitzer Prize for fiction (1953) and the Nobel Prize for literature (1954) to support their view.

Hemingway probably did more to influence the world’s literature than any other modern American writer. He worked hard at it. He would rewrite a page half a hundred times or more to get exactly what he wanted.

New York Daily News published this on July 1, 1961.

(New York Daily News)

New York Daily News published this on July 1, 1961.

(New York Daily News)

New York Daily News published this on July 1, 1961.

(New York Daily News)

He considered writing a job and a tough one and once noted: “Nobody but fools ever thought it was an easy trade.”

What he wrote about he knew. He was a master of writing the way people thought and talked and acted. He recognized that a braggart might also be a legitimate hero. Bullfighting was one of his favorite sports and he was considered an expert. He was pretty much an expert on danger, drinking and women, too.

Women, however, were probably the least dangerous of Hemingway’s pursuits, though he did get married four times and survived three divorces.

Began on Newspaper

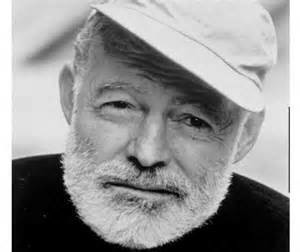

Hemingway, a burly, barrel-chested, shaggy man with a good head of hair and a stubbly beard – both turning white – began as a newspaperman and his later work showed it. Scores of writers emulated his concise, short, expressive prose style. He used cuss words when he thought that was the best way to express himself.

Few critics criticized his style, though many assailed the hard-living philosophy he wore through his novels,

The critics looked for significance in Hemingway and they all found it – sometimes to his amusement.

In this photo provided by the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum writer Ernest Hemingway appears sitting in front of his typewriter Cuba in the late 1940s.

(AP)

Matter of Interpretation

They found all manner of meanings, for example, in one of his more recent novels, “The Old Man and the Sea (which followed by a Pulitzer Prize the next year and the Nobel Prize the year after).

It was a simply told story of victory and defeat, the tale of an aged fisherman’s long, agonizing struggle to land the gigantic marlin that would cap his long, hard life. He catches it, but sharks nibble away on the fish before he can bring it to shore. Finally, there is just skeleton left.

Critics had a field day delving into the deeper meanings of the story, but Hemingway would not admit there was any symbolism involved. Since the critics were having so much fun explaining it all, he said, why interfere?

Hunted With Dad

Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, one of six children of an Oak Park, Ill., physician. Much of his boyhood was spent in Michigan. There he took to the outdoor life, including long hunting trips with his father. Hunting was to remain his steadfast love.

His father, Dr, Clarence Hemingway, committed suicide with a shotgun. Like the author, he had hypertension and incipient diabetes.

In high school, Hemingway played football and boxed. After graduation, he joined the Kansas City Star as a cub reporter, but soon after sailed to Italy to become an ambulance driver at the front in World War I.

He got two decorations, an aluminum kneecap, 247 wounds (by his own count) from mortar bursts, and a wealth of material for the novels which were to bring him world fame.

He shrugged off the medals, saying he got one for being an American and the other by accident. But from his experience he was to write what he himself considered one of the best war scenes ever described – the Italian retreat from Caporetto, which appeared in his classic novel of war and love, “A Farewell to Arms.”

Gertrude Stein Influence

He bounced around Europe after the war and was one of the young American writer influenced by the late Gertrude Stein, who was then holding court in Paris and displaying an astounding new technique at poetry to bemused world.

Hemingway’s first major published work was a short story collection, “In Our Time,” 1924.

Two years later, his first major novel, “The Sun Also Rises” – the story of an emasculated war veteran’s hopeless love – began his push into the literary world.

Novelist Ernest Hemingway, right, and his friend Aaron Edward Hotchner, left, pose after duck hunting in Ketchum, Idaho, in this 1958 photo taken by Hemingway’s fourth wife Mary.

(MARY HEMINGWAY/AP)

The pattern of much of his later writing – a bruising, brawling, drinking, dangerous life; deep and often frustrated love, a hero who bears the scars of war – was emerging.

Writer is Established

“Men Without Women,” also a collection of short stories, came out the next year.

In 1929, “A Farewell to Arms” was published and there was no doubt left that here was a major young American writer.

By that time, he had already married twice, first to Hadley Richardson (in 1921) and next to Pauline Pfieffer (in 1927). Both marriages ended in divorce, as did his third, in 1940, to writer Martha Gellhorn.

When he wasn’t writing, he tried fighting bulls in Spain and boxers in the ring. Even at advanced middle age, he reveled in his hard body (6 feet, 200 pounds) and liked to punch his friends in the stomach and be punched in return, to show everyone that he was still in shape.

He wrote “Death in the Afternoon,” a saga of bullfighters and the bull ring, in 1932; “Winner Take Nothing,” a collection of short stories, in 1933; “The Green Hills of Africa,” in 1935, and “To Have and Have Not,” a novel of smuggling and death in the Florida Keys, in 1937.

Ernest Hemingway, second from right, and Gianfranco Ivancich, right, dining with an unidentified woman, left, wife Mary Hemingway, second from left, and Juan “Sinsky” Dunabeitia, center at Hemingway’s villa Finca Vigia in San Francisco de Paula, Cuba.

(AP)

Hemingway had buzzed around covering minor wars in the Near East as a correspondent. When a real big one, the Spanish Civil War, came along, he was off like a shot to report it for the North American Newspaper Alliance.

Spain a Special Love

He loved Spain, had lived in it on and off for a dozen years and felt at home there. He was pro-Loyalist (as his novel, “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” published in 1940, demonstrated) and raised money to buy ambulances for the troops fighting Franco’s forces.

Among other Hemingway works relating to the Spanish conflict was “The Fifth Column.”

It was his only play and wasn’t much of a success, though it made the term “fifth column” a household word. He meant that the rebels had four columns advancing on Madrid and a fifth column of rebel sympathizers inside the city attacking the defenders.

Hemingway came close to death again in Spain. Three shells hit his hotel room, but he was unhurt.

Then Another War

Writer Ernest Hemingway sit with his fourth wife Mary in Cuba.

(AP)

Then World War II came along and again it was war correspondent Ernest Hemingway at the front, dressed in GI togs and carrying a handy flask or bottle to share with the troops. This time he was covering for Collier’s magazine.

A wartime blackout in London almost resulted in his death in 1944, when he was badly banged up in a traffic accident. But a short time later with 53 stitches in his head and protesting doctors in his wake, Hemingway was off for the Normandy beachhead in an attack transport.

Joins Free French

This time, mere reporting was not enough. He joined a fighting unit of the Free French, became a captain and helped capture six Germans. He later switched to correspondence again, this time for the U.S. 1st Army.

The U.S. gave him a Bronze Star.

Shortly after the war ended, he met and married his fourth and last wife, writer Mary Welsh, a trim little blonde who loved adventure as much as he did. She called him “Papa” and he called her “Miss Mary.” They were devoted.

Miss Mary was with him, too, when their small chartered plane crashed in 1954 in one of the wildest spots in Uganda.

Ernest Hemingway wears the look of the successful novelist in Paris, in 1927, just after his book, “The Sun Also Rises,” hit the bestseller list.

(AP)

Hemingway’s injuries included a burned arm and his wife had some broken ribs, but he said later: “I wouldn’t have missed a minute of it.”

Blood-Poisoning Bout

On other safaris, death came close when a wounded rhinoceros charged him and, still, again, when he developed a bad case of blood poisoning.

But he loved Africa too much to let anything like that daunt him. One of his best short stories, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” had an African setting.

So had “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” That was expanded into a movie as was another of his top short stories, “The Killers.” “A Farewell to Arms,” “To Have and Have Not,” “For Whom the Bell Tolls,” “The Sun Also Rises,” and “The Old Man and the Sea” also were made into movies.

As soon as their Uganda plane crash hurts healed, Hemingway and his wife were off fishing for the big ones off the dangerous coral reefs of Kenya.

Cuba was another favorite fishing spot for the author. He made his home on a farm in Cuba about 10 miles from Havana. When he wasn’t fishing, he was batting out copy at his desk.

Between 1940, when “For Whom the Bell Tolls” came out, and 1950, when “Across the River and Into the Trees” – one of his less successful books – was published, no major Hemingway work emerged and critics were telling each other that Hemingway was drying up.

Then came “The Old Man and the Sea.” Critics hail it.

EMH:: RIP