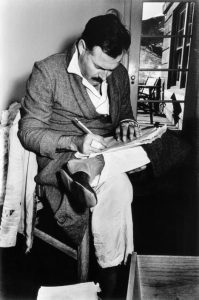

Library Corner: ‘A Farewell to Arms’ another banned classic

Special for the Grand County Library District

Grand County LIbrary District/Courtesy image

Ernest Hemingway’s novel about World War I, “A Farewell to Arms,” has been named one of the 100 best books of the 20th century. Scholars called it a masterpiece. But…

There’s another side to the story. “A Farewell to Arms” was banned multiple times since it was published in 1929 for sexual content, and for its honest treatment of war. It was banned in Boston, Ireland, Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy.

In the United States, parents sometimes demanded it be removed from school libraries. (Which would prompt students to read “A Farewell to Arms” faster than you can say sexual content.)

I fell in love with this book over 50 years ago when a high school English teacher assigned it. Hemingway presents an exquisite study of young women and men struggling to survive the violence of war. His love story is charged with elements that exceeded my experience at 16, which made it an even more powerful read the second and third time around. (If there are prostitutes in the book, and there are indeed, that’s because prostitutes work their trade in every war. It is a sad historical fact.)

The narrator, Lieutenant Frederick Henry, is a Red Cross ambulance driver for the Italian army’s campaign against Austria and Germany. After he’s seriously wounded, Frederick falls in love with Catherine Barkley, an English nurse working in an Italian hospital.

The plot builds tension in two directions. First, Frederick returns to the front after surgery and his ambulance crew transports increasing numbers of casualties, badly wounded soldiers. Second, Catherine becomes pregnant with his child, and her health soon deteriorates.

Hemingway sends his characters into the depths of melancholy where the reader ponders the story’s great irony. Both love and war carry risks that may be fatal. Over time, Frederick changes from a naive do-gooder to a stone-cold killer. He ends up shooting an Italian soldier for abandoning his comrades. War brings out the very best and the absolute worst in people.

The narrator explains, “I was always embarrassed by the words sacred, glorious and sacrifice and the expression in vain… and I had seen nothing sacred and the things that were glorious had no glory…”

Admittedly, this book isn’t for everyone. Its depiction of World War I combat rings as true today as scenes from Afghanistan. But it shouldn’t have ever been banned. Just as some people prefer a cup of tea to coffee, they don’t have the right to shut down Starbucks. No one individual or mob should have the right to ban a book that millions of readers might learn from.

Frederick Henry does not “end up shooting an Italian soldier for abandoning his comrades” – he shoots at two who are running away AWOL but misses. In perfect Hemingway fashion and in the novel’s best scene, Henry himself is taken aside during the Caporetto Retreat to be shot for the same reason. He calls bullshit on the whole war and jumps into a river to escape as a general who was next to him is executed.

This is the kind of cold irony that elevates these earlier works from what comes later – G.I. Joe Hemingway… the war hero who blows the bridge, the old officer who charms the Italian teen princess. The mother-child death at the end is a thousand times harder than anything from the war depicted, it’s a stone-cold gun punch. The war is just background noise, as in the very first chapter where he notes “only” 7000 died from Cholera during an outbreak. Mother Nature gets the first and last word in this book. As w/ “Sun Also Rises” (“Farewell to Arms” in my opinion is the real first novel, certainly the material he used came first) the woman dissipates into THAT GLITTERING THING YOU CAN NEVER HAVE. And he was dissed by both real-life women these characters were modeled on, he just elevates it to high literature.

Any time a feminazi come skulking calling him all kinds of nonsense, point out the “Hemingway hero” in Novel #1 has no dick and in Novel #2 goes AWOL in the war to be run to the arms of his (laughably motherly) nurse lover he knocked up. Our hero does not “get the girl.”

Thank you, Edward! Very interesting. (My MailChimp notifications are on the fritz and I just saw your comment or would have acknowledged earlier. I am very grateful for your insight and read it with much interest. Thank you for caring about Hemingway more than 60 years after his death. Best wishes, Christine