Hello! This is a sweet first love letter from Hemingway to a woman with no regrets: Read on for the article below. Best, Christine

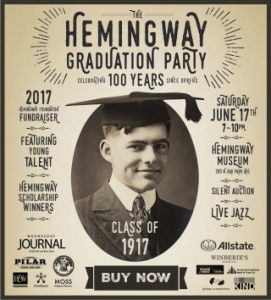

Hemingway Letters Pining For High School Love Interest Found In Marblehead

Ernest Hemingway, the legendary author and tortured Nobel laureate, is known for works like “A Farewell to Arms” and “The Old Man and The Sea.”

His image was that of a bold adventurer and world traveler. He was an avid big game hunter, often posing next to his prey in pictures.

There’s another — and perhaps more relatable — side to the legendary author, though. It’s one of an awkward teenage suitor trying desperately to impress a girl who captured his high school heart.

Her name was Frances Elizabeth Coates. She sang opera and went to the same Oak Park, Illinois high school Hemingway attended. He played cello at the time and was enamored by Coates and her love of art.

Coates’ granddaughter, Betsy Fermano, lives in Marblehead, Mass. She kept Hemingway’s letters to her grandmother since Coates’ death in 1988. She seals the letters in a quart-sized plastic bag and was keeping them in a trunk. She only recently started dropping them off in a vault at a nearby bank when she learned they could be of value. They’re slightly yellowed but in surprisingly good condition for papers that are essentially a century old.

“I remember my grandmother telling me about these letters, and she was very embarrassed to talk about her relationship with Ernest Hemingway — or Ernie as she always called him,” says the retired fundraising and development executive. “Because they were really close friends … and I guess Ernie wasn’t with, so I’ve heard, a lot of women, and he was really close to my grandmother, to Frances, and they spent a lot of time together.”

Elder (A Hemingway Scholar) says the preservation of Hemingway’s letters is remarkable.

“Letters from that era — from 1918, 1919 — outside the family are extremely rare,” he explained. “It’s just his voice. He is just sort of free and flirtatious with her because he’s not writing to family.”

A portion of a letter written by Ernest Hemingway to Frances Coates in 1918. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

In the letters, a young Hemingway writes from Milan, Italy during World War I. We asked Fermano to read one of the letters Hemingway wrote from his hospital bed there in 1918 as he recovers from injuries suffered while volunteering as a wartime ambulance driver. He wrote:

“Dear Frances, you see, I can’t break the old habit of writing you whenever I get a million miles away from Oak Park. Milan is so hot that the proverbial hinges of hell would be like the beads of ice on the outside of a glass of Clicquot Club by comparison. However, it has a cathedral and a dead man, Leonardi Da Vinci and some very good-looking girls, and the best beer in the Allied countries.”

Elder said Hemingway seems to be “trying to make [Frances] jealous. He’s trying to say, ‘look at all these beautiful women around me,’ and then he’s bragging about trying beer, which would’ve been sort of the ultimate sign of rebellion, because he grew up in Oak Park, which was a town sort of founded on the temperance movement and was a dry town.”

Was Coates Hemingway’s First True Love?

“Given some of the evidence here, I think Frances Coates cared for him, but he was squarely what we call in the ‘Friend Zone,’ so if it was his first love, it was very one-sided,” explains Elder.

It was, it appears, unrequited love, then. In fact, in a letter that Francis Coates wrote to a Hemingway biographer, she described her once close friend as awkward and sensitive.

Coates went on to marry a classmate named John Grace, a future railroad executive. But Elder says apparently Hemingway, who pined over Coates as teenager, never forgot Coates — and maybe never got over her because, in fact, her name appears as a character in some of his now classic novels.

“Hemingway was good at holding grudges, and this is not really a grudge, but she is certainly someone he never forgot,” Elder says.

Hemingway apparently references Frances as a character when he’s talking about her husband, in which he writes in his novel, “To Have and Have Not”:

“He’s probably a little too good for Frances, but it will be years before Frances realizes this. Perhaps she will never realize it with luck. [This type of man] is rarely also tapped for bed. But with a lovely girl like Frances, intention counts as much as performance.”

Woo! Elder says “whether or not that was directed at [Coates], Frances definitely saw herself in that — she wrote about it, calling it a wry scene.”

Coates didn’t forget Hemingway either.

She kept his high school portrait in a gold frame in her drawer, and all of the pictures he sent her in a small envelope. Some of those are now in Marblehead as well.

So, did Francis Coates ever regret letting go of the young writer she called Ernie who later became a larger-than-life author — but who also went on to four marriages and three divorces?

Well, a little scribble on the back of an envelope may help answer that question.

“Oh, this is what she says on this envelope, ‘Ernie’s pictures. And 25 years later, ooh! Am I glad I married John!’ ” Fermano reads, laughing.