‘Lucky for him he could write’: Ken Burns takes on Ernest Hemingway

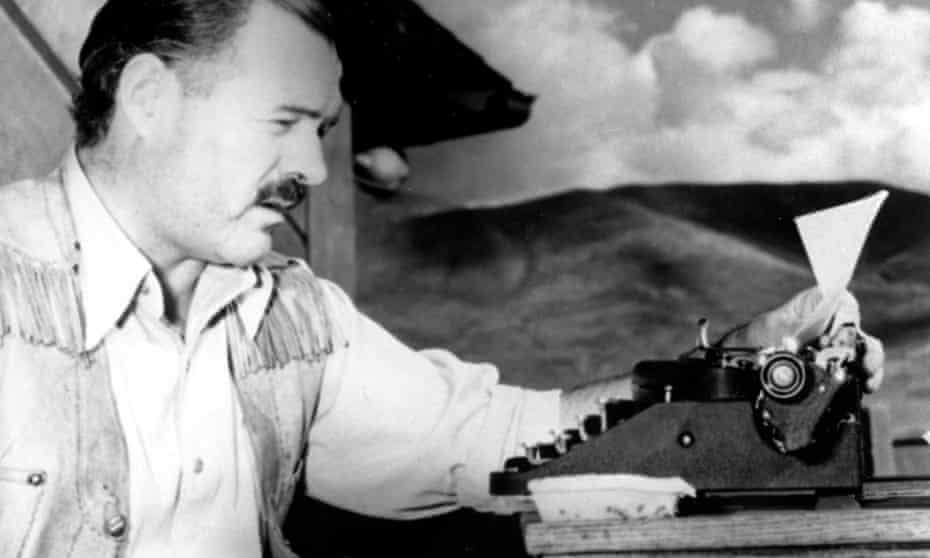

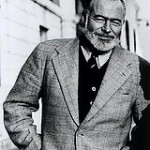

Ernest Hemingway at his typewriter as he works on For Whom the Bell Tolls at Sun Valley lodge, Idaho, in 1939. Photograph: AP

Too white, too male, too privileged – and according to some critics, that’s just one of the co-directors. A new PBS documentary on an American giant sails in stormy waters

Speaking at a press event for the new PBS documentary about Ernest Hemingway, the actor Jeff Daniels said of the man whose words he reads: “Lucky for him he could write.”

Over six hours, the co-directors Lynn Novick and Ken Burns subject a giant of American literature to an unsparing psychiatric exam.Ken Burns: How Vietnam War sowed the seeds of a divided AmericaRead more

“I was aware of this sort of edifice of the macho characteristic and good writing,” Burns said, about the scale of the task. “The writing only increased in its power and glory and majesty. And as I confronted all of this negative stuff, it became important that the art transcended it and basically didn’t excuse it. And we do not excuse him. And we hold his feet to the fire.”

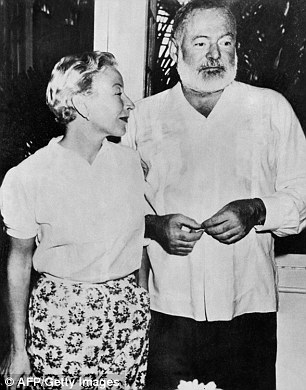

All of this negative stuff: Hemingway was married four times. He was psychologically and physically abusive. He used and wounded his friends. If unsurprisingly in a man born in middle-class Illinois in 1899, his views on race were prejudiced. He died by his own hand, at 61, 60 years ago.Advertisementhttps://33d6d92e8945d70fc2e39e370912f961.safeframe.googlesyndication.com/safeframe/1-0-37/html/container.html

In episode one of Burns and Novick’s film, the poet and scholar Stephen Cushman says it isn’t possible to “launder” Hemingway. The directors do not try. They have been working 40 years and have created a body of work built on the great 1990 series The Civil War that has grown to encompass jazz, baseball, the second world war, Vietnam and more.

With Hemingway, Burns said, they found that “as we often find with great artists, there is this terrible price to pay among those closest to that person and among the outer circle and, of course, most notably to one’s self.”

Novick “felt pretty clear that I didn’t like Hemingway the man and that I wasn’t sure how I am going to feel spending six hours with him as a viewer … and yet at the end, I think we have tried to get under his skin, as Edna would say. I felt a lot more compassion for him and his struggles and his demons.”

Edna O’Brien lights up the film. In episode one, the great Irish novelist defends Hemingway from a common charge: that he hated women.Edna O’Brien on turning 90: ‘I can’t pretend that I haven’t made mistakes’Read more

Of Up in Michigan, an early short story which describes a rape, O’Brien says: “I would ask his detractors, female or male, just to read that story. And could you in all honor say that this was a writer who didn’t understand women’s emotions and who hated women? You couldn’t. Nobody could.”

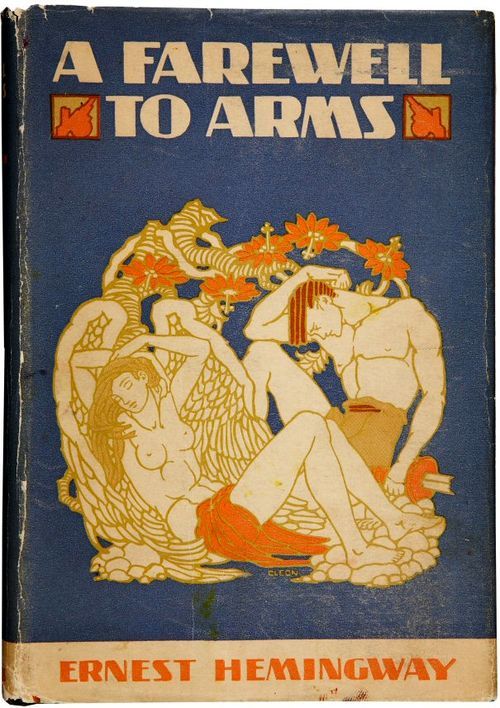

O’Brien also says A Farewell to Arms, the novel of the first world war which ends with a death in childbirth, “could have been written by a woman. I regard that as a compliment. Hemingway might regard it as an insult. But I don’t, because it is the androgyny in a man or a woman that allows them, even if briefly, to be able to put themselves inside the skin of the thing.”

The notion of Hemingway’s buried androgyny surfaced in the press session too.

“What we need is a more nuanced sense of his sexuality,” Burns said, “His very complicated and evolving sexuality. And in fact, Edna hits on it better, like, what is it in us that’s obligated to inhabit the other. And that’s an interesting part.”

“Maybe it was born when [Hemingway’s] mother twinned him, putting him in dresses and his sister in pants so that they could be alike. Maybe it is born of some other thing. But he has a curiosity about role changes. His wives cut their hair short, to look like boys. He wants them to call him ‘Katherine’ and he calls them ‘Pete’ in the bedroom. There’s some very interesting stuff.”

Appropriately for America in 2021, this is a Hemingway who inflicted trauma but also suffered it, including severe head injuries, which Burns and Novick examine.

And so to race. Never mind Hemingway – critics have spoken harshly of Burns’ own place in PBS’s output and his choice of subjects.

In short, are the director and those whose stories he tells too white and too male to be so strongly backed by the public broadcaster? Burns and Novick were duly asked about their “criteria for individuals who become worthy of their own series versus become included in a broader series”, as “it seems like it’s a lot of white politicians and artists and [the] only three black individuals have been athletes”.

“We pick subjects,” Novick said. “They pick us. It is a very organic process. And we focus on people from a whole wide diverse array of American characters and important figures in our history. So, I think we don’t really want to think about parsing our work into these kind of categories … We are pretty expansive in what we have taken on, what we’re interested in.”

Burns said: “I think Louis Armstrong deserved a 10-hour series by us, and just was the central part of the Jazz series. So too we could have done a biography of Frederick Douglass out of The Civil War, of many other subjects that we are doing that are complicated in that way, and many other people who aren’t getting the full treatment, that are constituent parts of these other things.”

Burns also said he was currently deeply involved in an eight-hour film about Muhammad Ali, due in September. But in the end, he said, choosing subjects “has to be done with your gut”.Ken Burns’s The Civil War: America’s greatest documentary rides againRead more

Hemingway’s own instincts included a need for wholesale slaughter and gutting, whether on African safari or from boats off the Florida Keys. But amid it all, Novick and Burns contend, whether hunting or watching bullfights or reporting from the bombarded cities of Spain, he found ways to pin humanity down on the page. If he has now become a problem, it is a problem that should at least be confronted.

“In some ways this is [our] most adult film,” Burns said. “I don’t mean that in any rating way. I mean that in how complicated it is to be able to tolerate contradiction, to be able to tolerate undertow, to understand that he could be one thing and the opposite of that thing at the same time.”

Daniels is not the only big name attached to the project. Meryl Streep voices the great journalist Martha Gellhorn, Hemingway’s third wife. Keri Russell, Mary-Louise Parker and Patricia Clarkson read the words of Hadley Richardson, Pauline Pfeiffer and Mary Welsh.

Daniels described a sort of cleansing experience. Hemingway, he said, has “a brevity and a simplicity that … just boils down to him telling you the truth. And there’s no adornment. Since doing the reading for Ken and Lynn, I have ceased using adjectives and adverbs because I felt so guilty. That’s what it felt like.

“And like Edna was saying, he inhabits the skin of his opposite, and that’s what actors do. That’s what great artists do. And it’s nice to know that those of us who are acting and do that didn’t invent it. People like Hemingway did.”

- Hemingway premieres on PBS from 5 to 7 April

+4

+4

in the offing.

in the offing.

had short, swept back curly blond hair that framed her face.

had short, swept back curly blond hair that framed her face.

. On occasion she called him Ernestine until he was about 6-years old. At that point he rebelled and demanded a hair cut and boy’s clothes as well as to be called by his real name. We can get psychological about the implications .

. On occasion she called him Ernestine until he was about 6-years old. At that point he rebelled and demanded a hair cut and boy’s clothes as well as to be called by his real name. We can get psychological about the implications .