Fascinating. 1925 Paris. Duff died very young at age 36 of tuberculosis as i recall. She was smart, beautiful, reckless, fascinating.

Read and enjoy. Best, Christine

The Untold Story of the Woman Who Inspired Hemingway to Write The Sun Also Rises

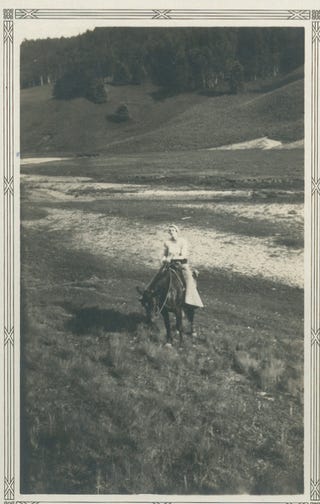

An exclusive look at the last known of photograph of Lady Duff Twysden.

by LESLEY M.M. BLUMEJUN 5, 2016

THE LAST KNOWN PHOTOGRAPH OF LADY DUFF TWYSDENPAPERS OF CLINTON KING, MATT KUHN COLLECTION

Several years ago, I came across a photograph of young Ernest Hemingway sitting at a cafe table with a group of people, including one beguiling, fashionable lady. There was something about the way she gazed at the camera; she managed to be both demure and coquettish. I soon learned that her name was Lady Duff Twysden, and that she had been the real-life inspiration for Lady Brett Ashley, Hemingway’s iconic femme fatale in his debut novel, The Sun Also Rises.

I was astonished at first; I have long been a Lost Generation obsessive, but I hadn’t realized that Brett was drawn from real life, and I wanted to learn more about her. I started looking for a compelling account of the full, real-life story behind The Sun Also Rises, and found nothing. I decided to write that book myself—Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway’s Masterpiece The Sun Also Rises—and spent many subsequent months in Lady Duff’s company.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY, HAROLD LOEB, LADY DUFF TWYDSEN, ELIZABETH HADLEY RICHARDSON (HEMINGWAY’S WIFE), DONALD OGDEN STEWART, AND PAT GUTHRIE AT A CAFE IN PAMPLONA, SPAIN, SUMMER 1925.ERNEST HEMINGWAY COLLECTION, JOHN F. KENNEDY PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

She was a tricky person to reconstruct. When she died, she left no known diaries, few surviving letters, no self-aggrandizing memoir—which was rather unusual within her coterie of publicity-seeking expats. Anyone and everyone who ever had a Hemingway connection seems to have turned it into a book at one point or another. Very few photos exist of Duff; I’ve only seen three from the 1920s, when she was allegedly at the peak of her allure.ADVERTISEMENT – CONTINUE READING BELOW

Much of what is known about Duff has been pieced together through the testimonies and writings of her contemporaries. When Hemingway met her in 1925, she was in her mid-thirties. A Brit, she had acquired her title by marriage, but was soon to lose it: she had come to Paris to weather a nasty divorce. Her aristocratic husband had remained back in the U.K. Though a notoriously hard drinker, she handled her liquor admirably for such a stylishly lithe creature.

“We were all in love with her,” recalled writer Donald Ogden Stewart. “It was hard not to be. She played her cards so well.”

Everywhere Lady Duff went, a flock of men sat at her feet, “listening to her every word, loving her looks and her wit and her artistic sensitivity,” as one former expat put it. “We were all in love with her,” recalled writer Donald Ogden Stewart. “It was hard not to be. She played her cards so well.” She treated her many admirers with a democratic flippancy, calling each of them “darling,” possibly because she couldn’t remember any of their names.

A few writers in the expat colony in Paris were already eyeing her as a muse for their writings, and it was perhaps only a matter of time before someone translated her on paper as a character in a novel.

Hemingway got there first. Even though he was married to his first wife, Hadley, when he met Duff, he reportedly became “infatuated” with her, according to one of his former Paris friends. The timing of Duff’s entrance into his life was auspicious: Hemingway was, at that moment, trying to stage a professional breakthrough and desperately needed material to create the all-important debut novel.

Lady Duff would soon provide the basis for the perfect anti-heroine. That summer, when Hemingway took an entourage to Pamplona, Spain, to take part in the San Fermin bullfighting festival there, Lady Duff came along, with two of her lovers in tow, no less.

As one might reasonably expect, the voyage was not a harmonious one. The outing quickly devolved into a Bacchanalian morass of sexual jealousy and gory spectacle. Hemingway nearly came to fisticuffs with one of Duff’s suitors, Harold Loeb; Duff herself materialized at lunch one day with a black eye and bruised forehead, possibly earned in a late-night scrap with her other lover, Pat Guthrie. Despite the war wound and atmosphere she was creating, Twysden reportedly glowed throughout the fiesta. The drama became her.

It also became Hemingway, but in a different way. Seeing Twysden there amidst all of that decadence triggered something in him. He realized that he finally had the basis for an incendiary story. The moment he and Hadley left Pamplona to watch bullfights throughout the region, he began transcribing the entire spectacle onto paper.

Suddenly every illicit exchange, insult, and bit of unrequited longing that had happened within his entourage during the fiesta had a serious literary currency. The story became a novel—eventually titled The Sun Also Rises—which he finished in just six weeks.

A FIRST EDITION OF ERNEST HEMINGWAY’S ‘THE SUN ALSO RISES’GETTY/HERBERT ORTH

In the end, The Sun Also Rises was a (barely) fictionalized account of the events that had gone down in Pamplona. Donald Stewart, who appeared in the book’s pages as “Bill Gorton,” was astonished that Hemingway was even passing it off as fiction: it was, in Stewart’s opinion, “nothing but a report on what happened … [it was] journalism.”

The first draft of the manuscript even contained the names of the real-life people up until the very last page. Lady Duff would not become Lady Brett until Hemingway revised the book. (He considered and rejected various names for her character, including “Lady Doris.”) Yet little about Lady Brett Ashley was fictional: in a later-omitted introduction to the book, Hemingway laid out Duff’s background in excruciating detail, from her failed marriage to her drinking habits to her physicality, including her sleek, boy-short haircut, then known as an Eton crop.

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART II

Thanks ! I am just rereading this classic and Hemingway in general and I’m loving your research sharing. Thank you

Thanks so much!! Great to meet another Hemingway fan! Thanks for reading,. Very best, Christine