9 Unforgettable Breakup Letters From History

“Going out with you was like going out with a priest.”

1. Agnes von Kurowsky to Ernest Hemingway

The inspiration for the romance in Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms was his own affair with Agnes von Kurowsky, a 26-year-old Red Cross nurse he met while recovering from a shrapnel injury in Milan, Italy, during World War I. A few months after Hemingway—who was only 19 at the time—returned to the U.S. to find a place for them to live together, he received a letter in which von Kurowsky not only ended their relationship but also confessed that the time apart had given her the distance she needed to realize that she’d probably never been in love with him.

To add insult to injury, von Kurowsky told him that she’d soon be marrying someone else (an Italian millionaire, though she didn’t mention that). “And I hope & pray that after you have thought things out, you’ll be able to forgive me & start a wonderful career & show what a man you really are,” she wrote.

2. Marlon Brando to Solange Podell

Solange Podell was a French cabaret dancer and actor who met Marlon Brando backstage after a 1947 Broadway performance of A Streetcar Named Desire (in which Brando played Stanley Kowalski, a role he’d reprise for the 1951 film adaptation). The two struck up a relationship, which Brando ended sometime in the late 1940s via a letter written in pencil (and bearing a few spelling errors):

“In order that you won’t think me a complete boor, I am writing you this letter to explain that because of an erratic, flighty, fly-by-night, temperment I wish not to humiliate and degrade your sentiments by seeing you only at my mood’s conveinence. Please accept this letter with an open heart as it is written with fourthright sincerity. I’m sorry I could not have tried harder to be less self indulgent and theirwith, a little more compatable. My intuitions were flawlessly scroupulous but my emotions, unfortunately, unstable. I will remember you with fondness, regard, and appreciation. When we meet in France (perhaps in October) I trust my behavior will be a trifle more adult.”

Brando signed off “with warmth” and a postscript asking that Podell pass along his “kind acknowledgements” to her mother, “if she’ll accept them.”

3. Edith Wharton to W. Morton Fullerton

In April 1910, The Age of Innocence author Edith Wharton penned one hell of a “What are we?” missive to her on-again-off-again beau, journalist W. Morton Fullerton, who was giving her emotional whiplash with his mercurial changes in behavior.

“I don’t know what you want, or what I am! You write to me like a lover, you treat me like a casual acquaintance!” she wrote. “I have borne all these inconsistencies & incoherences as long as I could, because I love you so much, & because I am so sorry for things in your life that are difficult & wearing … Only now a sense of my worth, & a sense also that I can bear no more, makes me write this to you. Write me no more such letters as you sent to me in England.”

Wharton was especially upset because she would have been fine with friendship, but Fullerton’s mixed messages prevented them from settling into any kind of comfortable dynamic. “My life was better before I knew you. That is, for me, the sad conclusion of this sad year. And it is a bitter thing to say to the one being one has ever loved d’amour,” she wrote.

4. Jackie Kennedy to R. Beverley Corbin Jr.

While at Miss Porter’s School in Connecticut during the mid-1940s, a teenaged Jackie Kennedy (then Bouvier) dated a Harvard University student named R. Beverley Corbin Jr. Her letters to him, usually addressed to “Dearest Bev” or “Buddy darling,” shed light on her feelings about boarding school (which she hated) and about Bev himself, whom she came to realize she didn’t actually love.

In one letter from January 20, 1947, she wrote, “I’ve always thought of being in love as being willing to do anything for the other person—starve to buy them bread and not mind living in Siberia with them—and I’ve always thought that every minute away from them would be hell—so looking at it that [way] I guess I’m not in love with you.”

She kept up correspondence with him after that, but the relationship eventually fizzled, and in 1951 she quashed any potential for a rekindling of it when she told him she was engaged to someone else. “What I hope for you is for the same thing to happen as quickly and as surely as it did with me. It will when you least expect it,” she wrote to Corbin. (She called off her own engagement after just a few months and tied the knot with John F. Kennedy in 1953.)

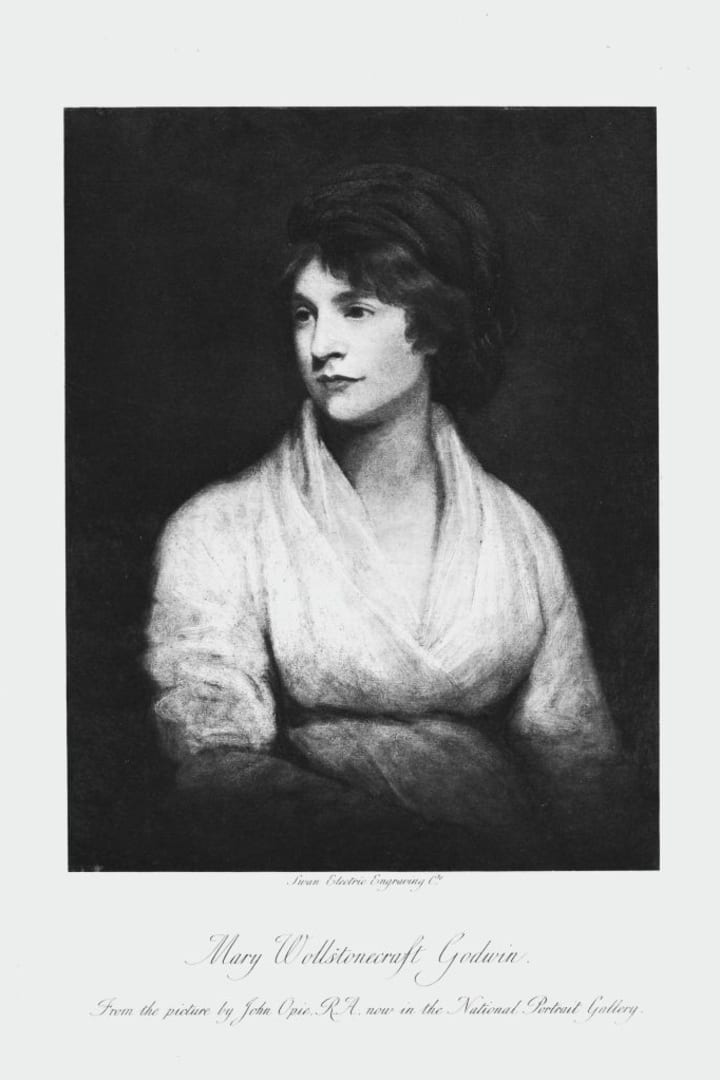

5. Mary Wollstonecraft to Gilbert Imlay

Before Mary Wollstonecraft married William Godwin and gave birth to future Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, she had a daughter with Gilbert Imlay, an American author and diplomat. They never officially married, and Imlay’s constant traveling, infidelity, and generally poor treatment of Wollstonecraft effectively killed their relationship. In March 1796, Wollstonecraft sent her former lover what could aptly be described as an 18th-century version of a “Delete this number” text.

“You must do as you please with respect to the child.—I could wish that it might be done soon, that my name may be no more mentioned to you. It is now finished.—Convinced that you have neither regard nor friendship, I disdain to utter a reproach, though I have had reason to think, that the ‘forbearance’ talked of, has not been very delicate.—It is however of no consequence.—I am glad you are satisfied with your own conduct,” she wrote. “I now solemnly assure you, that this is an eternal farewell.”

6. Frida Kahlo to Diego Rivera

In 1953, Frida Kahlo was lying in a hospital bed trying to quickly finish a letter before doctors amputated her gangrene-infected leg. She was writing to her husband, Diego Rivera, who had carried on affairs—including one with Kahlo’s own sister, Cristina—throughout their relationship. (To be fair, Kahlo wasn’t faithful to him either.)

“Let’s not fool ourselves, Diego, I gave you everything that is humanly possible to offer and we both know that. But still, how the hell do you manage to seduce so many women when you’re such an ugly son of a bitch?” she wrote. “I’m writing to let you know I’m releasing you, I’m amputating you. Be happy and never seek me again. I don’t want to hear from you, I don’t want you to hear from me. If there is anything I’d enjoy before I die, it’d be not having to see your f***ing horrible bastard face wandering around my garden.”

She then readily contradicted herself by signing off like this: “Good bye from somebody who is crazy and vehemently in love with you.” The two didn’t cut ties after Kahlo’s operation.

7. Richard Burton to Elizabeth Taylor

Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor had been married for nearly a decade when Taylor broke things off, and Burton immortalized his reaction in a letter dated June 25, 1973. “So My Lumps,” it begins, “You’re off, by God! I can barely believe it since I am so unaccustomed to anybody leaving me. But reflectively I wonder why nobody did so before.”

He vacillates between praising her (“Don’t forget that you are probably the greatest actress in the world.”), criticizing himself (“I am a smashing bore and why you’ve stuck by me so long is an indication of your loyalty.”), and painting a portrait of what his life will look like without her.

“I shall miss you with passion and wild regret,” he says. “You may rest assured that I will not have affairs with any other female. I shall gloom a lot and stare morosely into unimaginable distances and act a bit—probably on the stage—to keep me in booze and butter, but chiefly and above all I shall write.”

The Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? stars officially divorced in June 1974, but ended up remarrying in October 1975 (and then got divorced again less than a year later, though they remained close until Burton’s death in 1984).

Writer Anaïs Nin and occasional poet C.L. “Lanny” Baldwin were both married when they began an affair in 1944, but by late summer the following year it had started to self-destruct. Baldwin accused her of being jealous and called her “a kind of dog in the manger with men, [wanting] them all to sit at your feet and be yours, all yours and only yours.”

Nin, who considered Baldwin extremely insecure both as an artist and as a man, practically laughed off his claims, explaining that she only sought affection elsewhere after realizing their own relationship was “dead” and Baldwin could “never enter [her] world”—one of passion, love, and the art that comes from it. “Going out with you was like going out with a priest,” she wrote in a letter postmarked August 25, 1945.

9. Oscar Wilde to Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas

In early 1897, as Oscar Wilde was nearing the end of his two-year prison sentence for “gross indecency” (having relationships with men), he wrote a 55,000-word letter to his lover Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas, who hadn’t kept up correspondence with Wilde during his incarceration. Wilde berated Douglas for his insatiable need to control, which Wilde felt he himself had been subsumed by.

“Knowing that by making a scene you could always have your way, it was but natural that you should proceed, almost unconsciously I have no doubt, to every excess of vulgar violence. At the end you did not know to what goal you were hurrying, or with what aim in view. Having made your own of my genius, my willpower, and my fortune, you required, in the blindness of an inexhaustible greed, my entire existence. You took it,” Wilde wrote. “Your pale face used to flush easily with wine or pleasure. If, as you read what is here written, it from time to time becomes scorched, as though by a furnace-blast, with shame, it will be all the better for you.”

The letter is a searing takedown, and without historical context you’d assume it was a death knell for the relationship. But soon after Wilde’s release from prison, he and Douglas were back on. “Everyone is furious with me for going back to you, but they don’t understand us,” Wilde wrote in August 1897. “I feel that it is only with you that I can do anything at all. Do remake my ruined life for me, and then our friendship and love will have a different meaning to the world.”

Moreover, Douglas claimed not to have known about Wilde’s prison letter for years. Upon his release, Wilde turned it over to his friend Robert Ross with instructions to make a copy and send the original to its intended recipient. According to Douglas, Ross never did (though not everyone believes that). What Ross definitely did do was publish excerpts from the letter several years after Wilde’s death under the title De Profundis.

“If I had received the letter, the whole course of subsequent history might have been altered,” Douglas wrote in his 1929 autobiography. “My indignation at Wilde’s grotesque lies and misrepresentations, and his abuse and insults, would perhaps have cured me once for all of my infatuation for him, which still survived so strongly in those days. Again, on the other hand, it is possible, and indeed probable, that I would have forgiven him.”