An interesting article on Hem and Fitz

By ANDRIA DIAMOND April 22, 2017

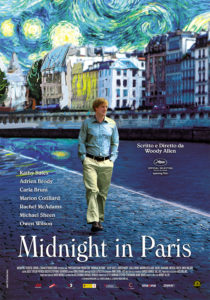

If you’ve ever seen the movie Midnight in Paris then you are familiar with the rose colored glasses romanticists often wear when thinking of the past. In the film, writer Gill Pender (played by Owen Wilson), somehow manages to travel back in time to 1920s Paris and meet many of the greatest minds in literature, including Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In this particular movie, the two historical writers seem to be cordial, Fitzgerald is handsome and sociable while Hemingway is philosophical and intense. Though Midnight in Paris is immensely enjoyable, it may not be wholly accurate in it’s portrayal of the relationship between these two phenomenal writers. History would suggest that their relationship was much more complex.

Hemingway and Fitzgerald first met in May of 1925, two men with extraordinary talent who were both battling their respective demons. Though they originally were good friends, their interactions later turned less amicable. Hemingway, though impressed with Fitzgerald’s writing, never seemed to respect the writer himself. He was wary of Fitzgerald’s need for validation, his tumultuous relationship with Zelda, and his self-destructive drinking habits. In a letter to Arthur Mizener (Fitzgerald’s biographer) dated April 5, 1950, Hemingway wrote:

“I believe that basically you write for two people; yourself to try to make it absolutely perfect; or if not that then wonderful; Then you write for who you love whether she can read or write or not and whether she is alive or dead. I think Scott in his strange mixed-up Irish catholic monogamy wrote for Zelda and when he lost all hope in her and she destroyed his confidence in himself he was through.”

Although Hemingway’s feelings toward Fitzgerald are clear, the facts with which he fuels them are decidedly less so.

Hemingway_Vs_Fitzgerald.pngHemingway had a flair for the dramatics, and his accounts of people and experiences could rarely be relied upon as gospel truth. Hemingway denounces Fitzgerald in his posthumously published memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964), and also deals roughly with the likes of Gertrude Stein and Ford Maddox Ford. In fact, we’ve recently documented Hemingway’s distaste for Ford Maddox Ford. While history shows it is not uncommon for writers to take issue with other creative minds, Hemingway had a lengthy track record for doing just that. It is speculated by literary devotees and historians alike that Hemingway’s harsh opinion of others was an act of self-preservation, as he seemed to be a man with a big ego and an even bigger chip on his shoulder. He was sensitive to the slightest condescension (which Fitzgerald did not mind providing) and often reacted with a sharp tongue.

While I would love nothing more than to imagine Hemingway and Fitzgerald—these two great minds—strolling through the 1920s as comrades, success rarely comes without sacrifice. Hemingway’s stubbornness and brash masculinity were essential in his work, just as Fitzgerald’s social perspectives and charm were essential in his. The very personalities and behaviors that made for different men are the same that made for great writers, and the world is a better place for it.