Play and enjoy courtesy of Quincy Perkins, of Key West, Florida! Lovely look at part of the home, the cats and a bit of the cats’ history, and Quincy’s own dark humor and take on it all as a kid growing up with its aura nearby. A glittering Gem. 5 minutes of fascination. Thank you, Quincy and his creative colleagues! Best, Christine

Month: June 2017

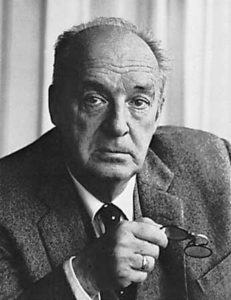

Ezra Pound, Hemingway, Politics that split them up.

My friend Trudy found this interesting Article about the writers of Paris in the ’20s. I edited it to shorten but I think you will enjoy it. Photos added by me.

Best, Christine

Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound’s friendship spanned continents—and ideologies.

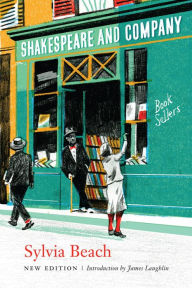

Ernest Hemingway, fresh off his marriage to Hadley Richardson, his first wife, arrived in Paris in 1921. Paris was a playground for writers and artists, offering respite from the radical politics spreading across Europe. Sherwood Anderson supplied Hemingway with a letter of introduction to Ezra Pound. The two litterateurs met at Sylvia Beach’s bookshop and struck up a friendship that would shape the world of letters.

They frolicked the streets of Paris as bohemians, joined by rambunctious and disillusioned painters, aesthetes, druggies, and drinkers. They smoked opium, inhabited salons, and delighted in casual soirées, fine champagnes, expensive caviars, and robust conversations about art, literature, and the avant-garde. Pound was, through 1923, exuberant, having fallen for Olga Rudge, his soon-to-be mistress, a young concert violinist with firm breasts, shapely curves, midnight hair, and long eyebrows and eyelashes. She exuded a kind of mystical sensuality unique among eccentric highbrow musicians; Pound found her irresistible.

Pound was known for his loyalty to friends. Although he had many companions besides Hemingway—among them William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, T.S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, Robert McAlmon, Gertrude Stein, e.e. cummings, Pablo Picasso, Wyndham Lewis, T.E. Hulme, William Carlos Williams, Walter Morse Rummel, Ford Madox Ford, Jean Cocteau, and Malcolm Cowley—Hemingway arguably did more than the others to reciprocate Pound’s favors, at least during the Paris years when he promoted Pound as Pound promoted others.

Pound edited Hemingway’s work, stripping his prose of excessive adjectives. Hemingway remarked that Pound had taught him “to distrust adjectives as I would later learn to distrust certain people in certain situations.”

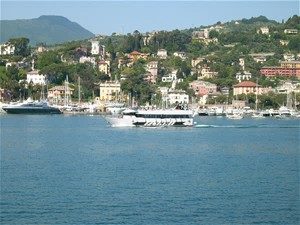

Pound, however, grew disillusioned with Paris, where his friends were gravitating toward socialism and communism. Paris, he decided, was not good for his waning health. Hemingway himself had been in and out of Paris, settling for a short time in Toronto. In 1923, accompanied by their wives, Pound and Hemingway undertook a walking tour of Italy. The fond memories of this rejuvenating getaway inspired Pound to return to Italy with his wife Dorothy Shakespear in 1924. They relocated, in 1925, to a picturesque hotel in Rapallo, a beautiful sea town in the province of Genoa.

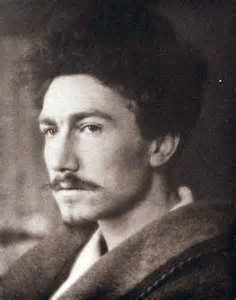

Young Ezra

The move to Italy also effectively terminated Pound’s glory years in Paris, about which Hemingway wrote affectionately:

More than anything else, Italian politics—and the rise of fascism—damaged Hemingway’s regard for Pound, who became a zealous supporter of Mussolini and a reckless trafficker in conspiracy theories.

Hemingway offered Pound some money, sensing that money was needed, but Pound declined it.

The falling out was no secret, and other writers took sides. William Carlos Williams wrote to Pound in 1938, saying, “It is you, not Hemingway, in this case who is playing directly into the hands of the International Bankers.”

Archibald MacLeish helped to orchestrate Pound’s release from St. Elizabeth’s, (A mental asylum Pound had been committed to. See below as to how he got there.) drafting a letter to the government on Pound’s behalf that included Hemingway’s signature, along with those of Robert Frost and T.S. Eliot. A year later Hemingway provided a statement of support for Pound to be used in a court hearing regarding the dismissal of an indictment against Pound.

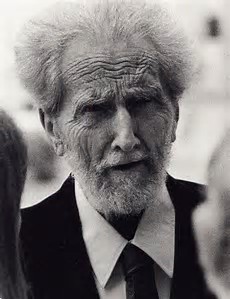

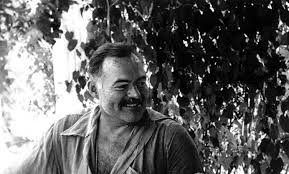

Hemingway awoke on the morning of July 2, 1961, put a 12-gauge, double-barreled shotgun to his head, and, alone in the foyer of his home, blew his brains out. He was 61. Pound’s friends and family didn’t tell him about Hemingway’s death, but a careless nurse did, and Pound reacted hysterically. The older of the two, Pound, at 72, was free from St. Elizabeth’s, where he’d spent 12 solemn years. He had returned to his beloved Italy to finish out his long and full life. In the autumn of 1972, he died peacefully in his sleep in Venice, the day after his birthday, which he’d spent in the company of friends.

Allen Mendenhall is an associate dean at Faulkner University Thomas Goode Jones School of Law and executive director of the Blackstone & Burke Center for Law & Liberty.

ME here: I may have over-edited re: how Ezra ended up in a psych facility. Ezra Pound was closely aligned with the Fascists in Italy. He was later imprisoned in Pisa by the liberating American forces in 1945 on charges of treason. In Pisa, he purportedly was placed in a small 6 x 6 cell and had a mental breakdown. He was ultimately sent to St. Elizabeth’s psychiatric hospital in Washington D.C. for 12 years. Friends including Hemingway sent money and petitions for his release which finally happened. While most acknowledged that he was a bit “crazy,” most felt he was far from any sort of danger to anyone including to his country. Once released he returned to Italy and died in Venice eleven years after Hemingway’s death. Christine

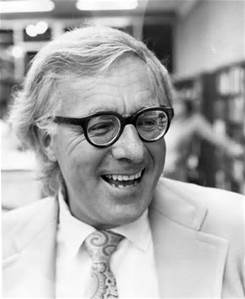

The Styles of the Novelists

I just read an article by Kevin Knudson, which appeared on April 30 in Forbes Magazine. It was a book review of Nabokov’s Favorite Word Is Mauve, by Ben Blatt. Noting that famous novelists write in their own particular style: Hemingway and the short sentences, Henry James and the longer ones, Virginia Woolf in the free-flowing stream of consciousness, Mr. Blatt, who’s a scientist, wanted to determine if you could figure out who the author was just by examining the pattern of his or her words.

The first chapter tackles the rule that all of us writers learned early, i.e. to use adverbs sparingly. Blatt took it to the scientific level. He took a corpus of novels written by a broad spectrum of famous writers and counts the “LY” adverbs. Here’s what you’ve got:

Author Books looked at Adverbs per 10,000 words

Hemingway 10 80

Mark Twain 13 81

Amy Tan 6 83

Steinbeck 19 93

Vonnegut 14 101

Updike 26 102

Rushdie 9 101

King 51 105

Dickens 20 108

Virginia Woolf 9 116

Blatt goes on to determine if each author is uniformly efficient or does it vary from book to book. Bringing it home to this blog, the question is: Hemingway the most efficient or just the most efficient on average. It turns out that William Faulkner wrote three books with a lower adverb rate (As I Lay Dying, The Sound And The Fury, The Unvanquished), than Hemingway’s lowest count, To Have and Have Not.

Blatt also looks at the number of exclamation points per 100,000 words. Elmore Leonard once said, “You are allowed no more than 2 or 3 per 100,000 words.” He actually used 49 per 100,000, but that still made him “one of the stingiest.” Tom Wolfe used 929 per 100,000. But the “winner” is James Joyce’s 1105 per 100,000. Most clichés? James Patterson the highest; Jane Austin the lowest. In addition, Blatt looks at what words an author uses more often than the average. He set out the following requirements to judge this issue:

- The word must be used in at least half of the author’s books.

- It must be used at a rate of at least once per 100,000 words.

- It must be obscure in the sense that it is not commonly used.

- It is not a proper noun.

Based on those criteria, Ray Bradbury’s favorite words are: icebox, dammit, exhaled. Nabokov’s favorite word was, in fact, mauve.

So, some scientists have really buckled down and used their training to illuminate, and to have a bit of fun! Interesting data that’s not quite trivia.

Love,

Christine

How to Tell if You are in a Hemingway Novel

This is part of a series that Mallory Ortberg has done (how to tell if you are in a Bronte novel, etc.) I read it in THE TOAST. I found it hilarious. If you don’t, you probably don’t read enough Hemingway. Hope you enjoy it as much as I did. Best, Christine

1. Everyone you know respects you. This disgusts you.

1. Everyone you know respects you. This disgusts you.

2. The door is white and the day is hot. This pleases you.

3. A Jewish man believes you are his friend. This disgusts you.

4. You are a man. A man! A man is a man like a tree is a tree.

5. A Greek man is shouting incomprehensibly at you. This is why you are drunk.

6. You have lost something in a war. This is why you are drunk.

7. A woman is looking at you. She is wearing her hat in a manner you find unbearably independent and mannish. You despise her.

8. You are standing on top of a mountain. The mountain admires you for climbing it. You do not care what the mountain thinks of you, and you light a cigar. The cigar admires you for smoking it. You sneer casually at the sun. Somewhere there is a white door.

9. You are shooting a large animal but thinking about a woman. You cannot shoot her. This infuriates you.

10. You met a homosexual once in Paris. It took you two years snowshoeing across the backcountry in Michigan to recover.

11. You have said goodbye to a young girl with a white face on a black train. You are ready to die.

12. Waiter bring me another rum

13. You hate every single one of your friends. You have no friends. You are alone at sea. How you hate the sea, but how you respect the fish inside of it. How you hate the kelp. How indifferent you are to the coral.

14. Your stomach hurts; that is how you know you are alive.

15. You are standing in a river and something is coming to kill you. You will welcome it with open arms and a booming laugh when it comes.

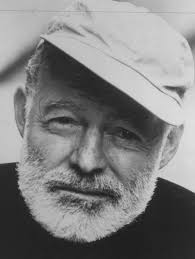

Hemingway and Fitzgerald: more thoughts

An interesting article on Hem and Fitz

By ANDRIA DIAMOND April 22, 2017

If you’ve ever seen the movie Midnight in Paris then you are familiar with the rose colored glasses romanticists often wear when thinking of the past. In the film, writer Gill Pender (played by Owen Wilson), somehow manages to travel back in time to 1920s Paris and meet many of the greatest minds in literature, including Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In this particular movie, the two historical writers seem to be cordial, Fitzgerald is handsome and sociable while Hemingway is philosophical and intense. Though Midnight in Paris is immensely enjoyable, it may not be wholly accurate in it’s portrayal of the relationship between these two phenomenal writers. History would suggest that their relationship was much more complex.

Hemingway and Fitzgerald first met in May of 1925, two men with extraordinary talent who were both battling their respective demons. Though they originally were good friends, their interactions later turned less amicable. Hemingway, though impressed with Fitzgerald’s writing, never seemed to respect the writer himself. He was wary of Fitzgerald’s need for validation, his tumultuous relationship with Zelda, and his self-destructive drinking habits. In a letter to Arthur Mizener (Fitzgerald’s biographer) dated April 5, 1950, Hemingway wrote:

“I believe that basically you write for two people; yourself to try to make it absolutely perfect; or if not that then wonderful; Then you write for who you love whether she can read or write or not and whether she is alive or dead. I think Scott in his strange mixed-up Irish catholic monogamy wrote for Zelda and when he lost all hope in her and she destroyed his confidence in himself he was through.”

Although Hemingway’s feelings toward Fitzgerald are clear, the facts with which he fuels them are decidedly less so.

Hemingway_Vs_Fitzgerald.pngHemingway had a flair for the dramatics, and his accounts of people and experiences could rarely be relied upon as gospel truth. Hemingway denounces Fitzgerald in his posthumously published memoir, A Moveable Feast (1964), and also deals roughly with the likes of Gertrude Stein and Ford Maddox Ford. In fact, we’ve recently documented Hemingway’s distaste for Ford Maddox Ford. While history shows it is not uncommon for writers to take issue with other creative minds, Hemingway had a lengthy track record for doing just that. It is speculated by literary devotees and historians alike that Hemingway’s harsh opinion of others was an act of self-preservation, as he seemed to be a man with a big ego and an even bigger chip on his shoulder. He was sensitive to the slightest condescension (which Fitzgerald did not mind providing) and often reacted with a sharp tongue.

While I would love nothing more than to imagine Hemingway and Fitzgerald—these two great minds—strolling through the 1920s as comrades, success rarely comes without sacrifice. Hemingway’s stubbornness and brash masculinity were essential in his work, just as Fitzgerald’s social perspectives and charm were essential in his. The very personalities and behaviors that made for different men are the same that made for great writers, and the world is a better place for it.